Prudence Crandall and the Massachusetts Volunteer Militia

Today I offer readers another installment in the history of investment firm Hayden, Stone & Co. This installment involves my ancestor, Prudence Crandall of Connecticut, and the men of Massachusetts’ Civil War-era Volunteer Militia (MVM). After the Civil War, the MVM became a clubby conduit for Boston politicos looking for Washington D.C. cash. The MVM was Charles Hayden’s springboard into Boston finance and its eventual financing of Silicon Valley, after decades of US government support.

The connection here is that both Prudence and the violent abolitionists who controlled the MVM were cut from the same intellectual cloth: self-interested people who hid behind hypocritical self-righteousness. To be an effective hypocrite one has to hold two contrary ideas at once, or in other words, be able to dissociate from the truth. In 1850s Boston, this type of con-man congregated around The Liberator newspaper.

The Liberator masthead, notice the motto “Our Country is the World. Our countrymen are mankind.” National Parks Service.

In my book Lincoln’s Counterfeiters, I detail how these New England abolitionists were actually extremely exploitative of their American and foreign working populations— grotesquely so. Yet, they and their successors painted an image of themselves as principled Christians and the conscience of the nation. Nothing could be further from the truth. In our time, the same self-interested hypocrisy is shown by Lincoln’s financial heirs who developed Silicon Valley and the H1-B visa crisis, amongst others.

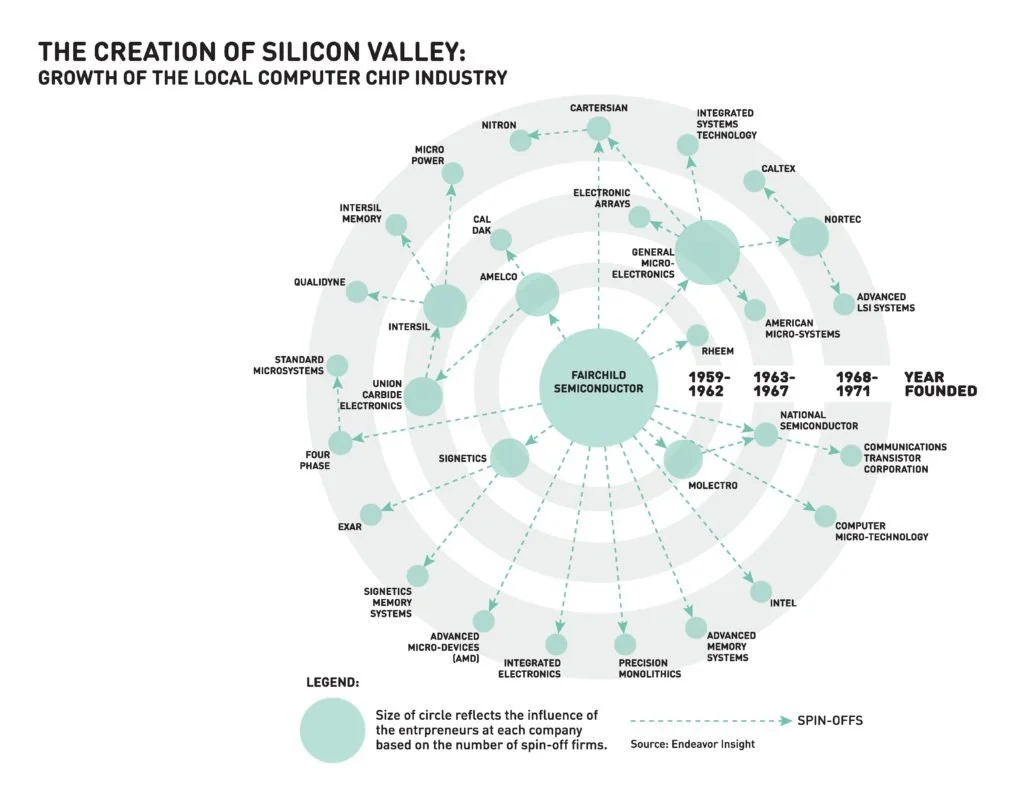

Now, in previous posts I’ve taken it for granted that readers understand the import of Fairchild Semiconductor for what has become Silicon Valley and the nasty politics that these tech companies promote. If you are not aware of Fairchild’s “Fairchildren” history, the following graphic from ComputerHistory.org may help:

This graphic follows Silicon Valley until the end of Hayden, Stone & Co. in the 1970s. For what happened later, please see my posts on Apple Computer, the Galician Gang (Jewish Mafia) and the CIA.

What these Silicon Valley histories leave out is that the money for Fairchild Semiconductor came from Hayden, Stone & Co. which was a Reconstruction profiteering outfit lead by men from the MVM. Lincoln’s abolitionist carpetbaggers. These are the anti-slave-power “Boston Copper” investors who abused their mining laborers in the late 1800s and are the direct financial predecessors to the H1-B visa bandits today. While these investors have talked about compassion and ethics since the 1850s, their history consistently shows that they exploit their vulnerable employees.

“Not good for Fairchild Semiconductor but pretty good for everyone else.”

In a business where disgruntled employees leave to start the competition, any unethical Silicon Valley executive would seek workers who he can expel to countries where starting a business is hampered by a culture of corruption and all the horrors of a failed state. Lincoln’s supporters also thought this way, but they used “anti-slavery” rhetoric instead of “anti-racism” rhetoric to hide their self interest. Their India was the Reconstructed South.

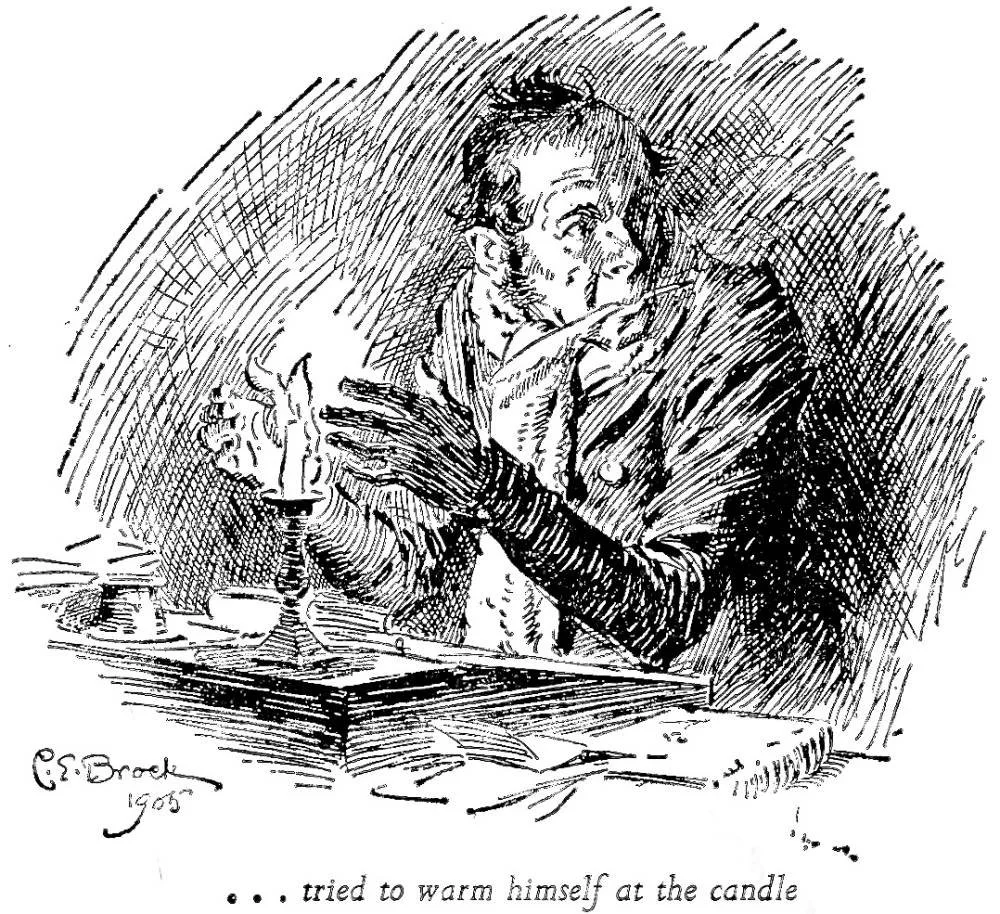

The more I learn about the money-men behind Lincoln, the more shocked I am by how closely their ethics match those of today’s “donor class”. Therefore, in the spirit of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, I bring to readers the sordid tale of how Lincoln’s partisans behaved in unchristian ways towards their employees and fellow citizens.

A New England Abolitionist “Little Miss”

In 1803 Prudence Crandall was born to Pardon and Esther Crandall, a well-off Quaker couple, of Hopkinton, RI. When Prudence was young her family moved to Canterbury, CT. She enjoyed the Quaker education, freedom and radical Protestantism that New England afforded young women of her time. She also enjoyed the good favor of the citizens of Canterbury, who chose her to serve as headmistress for a community-funded girls’ school.

But Prudence had a secret passion. An anti-slavery passion. Moved by accounts of black oppression in the South via The Liberator newspaper, Prudence found purpose in the abolitionist movement. She had never set foot in the South and knew only a few black people personally— mostly wealthy black people who had relocated northward prior to the 1850s. Prudence could pour all her virgin ardor into this cause which had the backing of so many wealthy and connected Northern patrons, such as the Seward family. Not only would she be righteous through this passion, she would also be well taken care of.

Prudence Crandall. This 1830s portrait was paid for Boston by newspaperman William Garrison.

Prudence decided that the best way to “serve the people of color” was to push for racial integration in the North. To that end, she admitted to her school the daughter of a local black farmer thereby creating the first integrated school in the United States. The other well-to-do families did not want their daughters to be guinea pigs in Prudence’s integration experiment, and some removed their daughters from Miss Crandall’s care. It was these families’ donations which had enabled the Canterbury school in the first place.

Prudence doubled down on her convictions and secretly traveled to Boston to consult abolitionists Samuel J. May and William Lloyd Garrison (owner of The Liberator), who gave her a hot list of black families who would entrust their daughters to her, a stranger, and the Canterbury community’s school. Prudence focused on an all-black student body, dismissed her remaining white students, and advertised in The Liberator for even more students. Prudence had hijacked Canterbury’s education resources to build a cell of “young Ladies and little Misses of color” from radical black families. Prudence received additional help from Arthur Tappan, a wealthy silk merchant (cheap labor consumer) and business partner of Samuel Morse. (We met Morse last week because his telegraph business turned into Lincoln’s Ringstrasse Information Bureau. Small world, no?)

Tappan was also an “Underground Railroad” trafficking network investor— as many cheap labor consumers in the North were. Displaced black labor drove down wages for low-skilled workers in New England and Canada. Radical New England industrialists had a remarkable way of reading God’s will into their business interests.

Unfortunately, Tappan’s “Undergraound Railroad” was not the idealistic institution that so many Quaker writers have portrayed it to be. It was a for-profit trafficking network, where runaway slaves paid traffickers to move them northward. It was a trafficking network subsidized by low-wage paying (or no-wage paying!) Northern employers such as the Seward family, who were spokespersons for infamous New England landlords like the van Rensselaers and Livingstons. These landlords forced their tenants to work for free and then sentenced those tenants according to slave-rebellion laws when they organized resistance. The most famous case of this was that of tenant William Pendergast in 1766.

The Underground Railroad’s middle-management had even less savory connections. Largely organized by Quakers and free Blacks, the Underground Railroad exploited pre-existing smuggling networks. For almost a century, Quakers had been disproportionately involved in counterfeiting bank notes, the same illegal business that Allan Pinkerton protected for Monroe, WI’s Bonelatta Gang along Chicago’s railroads. Pinkerton also used these Chicago tracks to smuggle trafficked slaves northward. His employees often came from the criminal underground themselves, typically smugglers and prostitutes. The “Underground Railroad” profits fed into other Northern organized crime networks.

Allan and Joan Pinkerton (his wife). Library of Congress

Once in Northern cities, escaped slaves were often sucked into the orbit of organized crime dons. They were both exploited and exploiters, commonly patronizing bordellos that sold working-class white women and children. (In NYC, the famous bordellos that catered to the interracial trade were owned by the Livingstons. Quaker involvement in the sex trade goes back to the English Civil War.) This toxic dynamic only increased when Lincoln gained power. An excellent example is that of Chicago’s black vice lord, “Mushmouth Johnson”, whose mother was alleged to have been a servant of the Lincoln family. Mushmouth would force Blacks in Chicago to vote according to whichever political party paid the most. He served Chicago’s Kentucky Colony overlords and raped the black, white and Chinese communities through vicious vice rackets. Mushmouth’s power only grew with Southern black immigration into overcrowded Northern cities.

John Mushmouth Johnson

The people who organized Tappan’s “Underground Railroad” were the best organized gangs of North America’s pre-1860 career criminals. Abolitionists often partnered with the most vicious elements of society. Would you want Miss Crandall’s school next door?

Arthur Tappan.

The citizens of Canterbury were strongly against “Miss Crandall's School for Young Ladies and Little Misses of Color”. As the history of Prudence’s “school” was written by the abolitionists and Quakers who pushed this form of integration, it is difficult to get a fair hearing of why Canterbury’s citizens didn’t want their school turned into an abolitionist institution. What is clear is that they were suspicious of the politicians’ motives and the character of the people such an institution would attract. Given the violence of other abolitionists promoted by The Liberator, this was entirely reasonable.

The citizens of Canterbury tried to reason peaceably with Prudence, from A Statement of Facts, Respecting the School for Colored Females, in Canterbury, Ct. Together With a Report of the Late Trial of Miss Prudence Crandall, Brooklyn, CT, 1833. Advertiser Press.:

On the day after the white scholars were dismissed, a Committee, composed of Rufus Adams, Daniel Frost, Jr. A. Harris, R. Fenner, (all of whom, were among her most efficient friends in establishing her former school,) visited her for the purpose of "persuading her, if possible, to give up her project, so far as Canterbury was concerned."—The propriety of the conduct of this committee, and the manner in which they presented to the lady, the objections which existed, to the course she was pursuing, has been spoken of in every instance, as highly creditable. It did not however, produce any visible effect, and consequently the same gentlemen were delegated from a larger body of the citizens of the town, to wait on Miss Crandall, on the 1st day of the following month. At this interview, every argumentative effort was made to convince her of the impropriety and injustice of her proposed measure. Daniel Frost, Jr., was appointed by the committee, to address Miss C., which was done, says one of the gentlemen, in a kind and affecting manner. In the course of his remarks, he alluded to the danger of the levelling principles, and intermarriage between the whites and blacks; when Miss C. made him the following reply,—"Moses had a black wife." This is not stated for the purpose of bringing censure upon the lady, but because her reply to the Com. seems to have been made in justification of the course she had adopted. The public must decide whether the amalgamation of the whites and blacks is a profitable or safe doctrine. The lady is not here charged with teaching that doctrine. The above reply was made by her to the committee, and every reader must decide its meaning, for himself.

Prudence wouldn’t follow Jesus’ teaching to reconcile quickly with her adversaries, so the town held a meeting on March 9th 1833 where it was resolved Miss Crandall’s school was a public nuisance:

…the obvious tendency of which would be, to collect within the time of Canterbury, large numbers of persons from other States, whose characters and habits might be various, and unknown to us, thereby rendering insecure, the persons, property and reputations of our citizens…

It is a fact confirmed by painful and long experience, and one that results from the condition of the colored people, in the midst of it white population, in all States and countries, that they are an appalling source of crime and pauperism.

The citizens of Canterbury didn’t want a black school because they were worried about what modern YouTubers describe as “ratchet behavior”. Don’t know what that means? Educate yourself.

Despite what Miss Crandall’s supporters might claim, the people of Canterbury were not monsters. They were truth-loving and cognizant of the limits of their own ability and responsibility to help the non-Connecticut-domiciled black population.

The desire of Canterbury’s residents was to support the resettlement of Southern blacks in Africa, from where other Africans forcibly sold their ancestors into foreign slavery. This was Abraham Lincoln’s stance too, until he figured out it conflicted with the interests of the labor brokers who supported him. Take a minute to read Canterbury’s statement, it’s a far more loving and eloquent document than the Quaker screeds in support of my ancestor.

What was Prudence Crandall’s motivation in all this? Certainly she drew attention to herself, and even spent a night in jail (much to her joy) in hard-hearted defiance of the concerns of her neighbors. She gave great press to The Liberator and was feted by William Garrison (who paid for her portrait) and “became the center of attention at abolitionist parties and gatherings each evening. The Boston abolitionists honored her as a true heroine of the antislavery cause.” [Prudence Crandall’s Legacy. Williams, 2014. P 174.]

Prudence didn’t win. Massive public opposition forced the closure of her “school” in 1834. She married another abolitionist, Bapitist minister Rev. Calvin Philleo, before fleeing Canterbury. However, Philleo turned out to be mentally ill and abusive so she left him in Illinois and espoused women’s suffrage instead. Her character is best described in her own words:

My whole life has been one of opposition. I never could find anyone near me to agree with me. Even my husband opposed me, more than anyone. He would not let me read the books that he himself read, but I did read them. I read all sides, and searched for the truth whether it was in science, religion, or humanity. I sometimes think I would like to live somewhere else. Here, in Elk Falls, there is nothing for my soul to feed upon. Nothing, unless it comes from abroad in the shape of books, newspapers, and so on. There is no public library, and there are but one or two persons in the place that I can converse with profitably for any length of time. No one visits me, and I begin to think they are afraid of me. I think the ministers are afraid I shall upset their religious beliefs, and advise the members of their congregation not to call on me, but I don't care. I speak on spiritualism sometimes, but more on temperance, and am a self-appointed member of the International Arbitration League. I don't want to die yet. I want to live long enough to see some of these reforms consummated. [“Prudence Crandall Champion of Negro Education”; M.R. and E.W. Small. The New England Quarterly. Vol. 17, No. 4 (Dec., 1944), pp. 528–529 ]

Does the character and fate of Prudence Crandall feel familiar? Check out Monroe, WI’s “Angle of the Seneca” Janet Jennings.

So, dear readers, that’s how I got my contrary streak. If all this was just limited to me, it wouldn’t be so bad. Unfortunately Prudence’s friends at The Liberator got an awful lot of power. Let’s talk about the Massachusetts Governor who set the stage for Hayden, Stone & Co’s rise to power: John Albion Andrew.

John Albion Andrew

John Albion Andrew was Massachusetts’s governor during the Civil War and a fiery abolitionist, far more so than Lincoln. He is Hayden, Stone & Co.’s link to power because he turned the “Massachusetts Volunteer Militia”, the governor’s personal bodyguard, into a political force during the conflict. It was through serving as an aide-de-camp to Andrew’s Republican successors that Charles Hayden became the brokerage face of Lincoln’s AT&T investor Governor Winthrop M. Crane. Crane owned more AT&T stock than anyone in the late 1890s; Hayden, Stone & Co. became Boston’s leading technology and mining brokerage.

J. A. Andrew was a politician of William Seward’s stripe. He opposed the “Know Nothing’ movement in Massachusetts, which was a popular movement to protect wages against cheap imported European labor. Freeing up black labor in the South meant cheaper wages for Northern Industrialists. To that end, he served as a pro bono lawyer for the terrorist John Brown during Brown’s murder trials with regard to his attack at Harpers Ferry, Virginia. Andrew was important to Virginian authorities’ investigation into Northern financial backing for John Brown too.

Cheap labor and breaking the power of Southern slaveholders were Northern Industrialist’s overriding goals. Since the 1776 revolution and the resulting Continental Congress, powerful Northern families like the Livingstons felt hemmed in by democracy-loving Southern plantation owners. Readers, if it was left to the New England aristocracy, we’d be living in a monarchy and no one would have the vote. It’s thanks to the Southern slave-owners that we’ve been spared that fate. During the Civil War politicians like the Sewards, who were inter-generational servants of these monarchist-loving families, found a way of breaking their Southern adversaries. The powerful abolitionists around Lincoln were deeply cynical people. [Read all about it in my book, Lincoln’s Counterfeiters!]

Just like Prudence Crandall, John Albion Andrew was influenced by the abolitionist agitator William Garrison, who published The Liberator from Boston. Andrew was a key figure organizing the Republican Party and its takeover of the Massachusetts government just prior to the war. He was elected governor in 1861 and proceeded to import a large number of free blacks to form the 54th and 55th Massachusetts Regiments. He wanted these to be lead by black officers, but his crew pressured him to choose white abolitionist men to lead the regiments instead.

Like many Northern abolitionists with little experience of the South, Andrew’s opinion of black Americans would arc from idolization to disappointment by the end of the war. By 1865 he didn’t think black suffrage in the South was such a hot idea and instead focused on running his “American Land Company and Agency”, a clearing house which specialized in selling Southern farm property to Northern investors so that Southern farmers could rent it back, a.k.a “carpetbagging”. [See “The Civil War party system : the case of Massachusetts, 1848-1876”, Baum, pp 104-105; and “Andrew Johnson and Reconstruction”, McKitrick P 226.']

Whatever his opinion of freed slaves, Andrew established a patronage channel leading from the Massachusetts Governorship to Washington D.C. via the “Massachusetts Volunteer Militia”. Over the next decades this honorary military body would be the vehicle for young Lincoln men on the financial make, like Charles Hayden. In fact, some of Charles Hayden’s earliest press in Boston was in connection with the MVM. Here’s the news:

Close up of the 1902 reportage above.

It was on the back of this connection to Governor Crane, the largest AT&T stockholder, that Charles Hayden built “Hayden, Stone & Co.” This Republican MVM pipline was just as important in 1905, when John Lewis Bates was elected:

Charles Hayden’s blurb is in the top half of column 3.

It is in this context that readers should place Hayden, Stone & Co’s subsequent shepherding of Lincoln’s telegraph men and their Western Union/AT&T electronic communications outfit… as well as Charles Hayden’s largess to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and ultimately Silicon Valley.

—

UPDATE: This one was kinda heavy, so I’d like to share with readers a light-hearted take on the MVM which I stumbled across waiting to adopt my new kittens. :) The ghosts of New Bedford’s 1903 MVM Armory rest uneasy….