Lincoln's Bucket Shops: Hollywood Pedophiles and Telegraph Stock Jobbers

A “bucket shop” was a pre-1910 gambling establishment. Working-class people could place wagers on how stock or commodities prices might change and were charged a small fee to do this. Most betting was done on the future price of grain and hog products determined at the Chicago Board of Trade exchange, or on cotton prices at the Atlanta exchange etc.. Typically, bucket shops would be run from saloons just like lower-class whorehouses. They were a staple moneymaker for '“Bossism”-era gangsters, less profitable than intoxicants or human trafficking, but also lower risk.

This is what the old commodity trading “pits” at the Chicago Board of Trade looked like.

When trading was in session, men would crowd into the pits and shout out the prices they were willing to pay for the commodity at auction. The little slips of paper were notes instructing the trader on what his boss wanted him to offer. Bucket Shop gamblers would take bets on the prices this system arrived at. A little creepy, no?

To put this in perspective, bucket shops profited off the small-time (low-information) “investor” in a way that wouldn’t be economically viable until 1970 with Ross Perot’s IBM spin-off “Electronic Data Systems”. Remember, readers, that Perot bought the forefather bank of Hambrecht & Quist to set up EDS and that Hambrecht & Quist serves the post-1970 Silicon Valley market just like Hayden, Stone & Co. served the pre-1970 Silicon Valley. Hambrecht & Quist’s forefather, Francis I. DuPont & Co., had bankrupted itself chasing those small “investors”.

Inside a 19th century “bucket shop”. Betting on fluctuations in the price of cotton was a mainstain, and the Atlanta exchange’s effort so stop providing bucket shops with information was central to putting these low-dollar gambling dens out of business.

Bucket shops could only exist because Western Union became the gatekeeper for timely financial information after the US Civil War. Western Union, Lincoln’s telegraph monopoly, would sell these saloon-based outfits a telegraph terminal dedicated to asset price information from the major exchanges in Chicago, New York City, Atlanta and St. Louis. By selling this information, WU broke a clause in their contract with these exchanges, but reasoning with the telegraph monopoly went nowhere for the exchanges. To complicate things, the exchanges had no problem with WU selling their information to “legitimate” brokers such as Hayden, Stone & Co.

Why was any of this a problem for the exchanges? A bet placed in a bar 100 miles from Chicago won’t change the price of pork. The problem came because bucket shops were making real trades through real board of trade member firms to influence the prices of the futures that the bucket shops’ gamblers were betting against. Bucket shops were a stacked house. The scale of the speculation in support of rigged gambling distorted honest commodity markets and that irked some board members. This is the summary of the judge’s findings in the CBoT’s successful 1903 case against bucket shops:

“Where it was proved that over 90 per cent, of the transactions executed in the pits of a board of trade were mere gambling transactions, which both parties intended to settle, by a payment of differences in the subsequent price of the commodities dealt in before the maturity of the option, quotations so obtained were of no legitimate value as tending to promote the commerce of the country, and dissemination thereof could not be restrained by such board of trade.”

In addition, the expensive “legitimate” brokerages were jealous of bucket shops’ huge, low-information client market— bucket shops carried something like 90% of commodity trading in the US countryside. [See “Partners in Crime: The Telegraph Industry, Finance, Capitalism, and Organized Gambling, 1870-1920” by David Hochfelder, IEEE History Center, Rutgers University.]

Stock brokers as well as commodity traders felt serious competition from bucket shops. One prominent broker on the New York Stock Exchange complained in 1889 that the “indiscriminate distribution of stock quotations to every liquor-saloon and other places has done much to interfere with business. Any person could step in a saloon and see the quotations.” Indeed, by 1889 competition from bucket shops had depressed the value of a seat on the New York Stock Exchange by nearly half, from $34,000 to $18,000, and a seat on the Chicago Board of Trade by over two-thirds, from $2500 to $800.

Trading floors like the Chicago Board of Trade and brokerages like Hayden, Stone & Co. were highly motivated to end bucket shops’ existence. “Legitimate” brokerages organized legal and public relations offensives against the bucket shop industry. Things got heated, for example:

One day in August 1887 President Abner Wright of the Chicago Board of Trade forcibly removed the instruments of the Postal Telegraph Company and the Baltimore and Ohio Telegraph Company from the floor of the exchange, literally throwing their equipment out of the building.

A few months later, on the night of December 15, Wright discovered some mysterious electrical cables leading out of the basement of the exchange building. Thinking that they were telegraph lines, he cut them with an axe. Wright was neither deranged nor a Luddite. Instead, his forceful actions were dramatic examples of the troublesome technological, cultural, and economic relationship between the telegraph industry, finance capitalism, and organized gambling in the United States during the Gilded Age and Progressive Era.

Wright’s actions occurred in the context of a 25-year struggle between the Chicago Board of Trade and hundreds of bucket shops. [Hochfelder]

Apart from the selfish financial interests of “legitimate” brokerages, there was justified opposition to bucket shops, which erupted into a cultural war from around 1870-1910. Gambling is a social evil and speculation hurts economic producers like farmers and manufacturers because of the havoc it plays with raw materials prices and the cost of financial insurance. Bucket shops were blamed for the evils of speculation, however, there was precious little difference between what the bucket shops were doing and what more sophisticated speculators like the trading floors or the brokerages were doing, so legislating away the bucket shops was difficult. (Just because an investor can afford higher trade commissions doesn’t mean they have better financial information.)

Lead by the example of the Chicago Board of Trade, Hayden, Stone & Co. did find a way of legislating away their bucket shop competition in 1906. This legal effort was spearheaded by Daniel Coakley, a Boston lawyer who AndreaNolen.com readers will know from orchestrating the 1917 “Mishawum Manor” underage prostitution trap. This trap gave the Roosevelt family leverage over Paramount Studio’s Galician Gang movie moguls (all pedophiles) to whom the Roosevelts handed the carcass of the Edison Trust.

Daniel Coakley was a labor organizer and a journalist before becoming a lawyer. Disbarred for unethical activities, the Roosevelts stepped up to have him reinstated. He became a prominent Democratic politician in Massachusetts.

Prior to WWI and the Roosevelt’s takeover of Paramount Studio, Paramount was a Mormon undertaking. In the decades after the Civil War Lincoln men were distrustful of the Mormons because both groups were powerful players in the same types of organized crime: chiefly counterfeiting but also selling intoxicants and human trafficking. Some time in the 1890s, when counterfeiting became less profitable, the Lincoln men and the Mormons resolved their differences and could work together (see Leon Goetz’s submarine patent and secret international warship building by Brigham Young’s family).

When the Roosevelts took Paramount, the monopoly film distribution outfit, the family took it out of Mormon hands and put it into the hands of Jewish organized crime (the “Galician Gang”). Here’s my description of the “Mishawum Manor” operation from a few years ago:

With Guaranty Trust’s horse hobbled, disaster befell [Adolf] Zukor and his entourage at Paramount shortly thereafter. In the wake of a victory party at the Copley Plaza hotel in Boston, Hiram Abrams lead Zukor, Walter Green, Jesse Lasky, lawyer Joseph Levenson, Harry Asher and Edward Golden to a bordello named “Mishawum Manor” where madam Brownie Kennedy supplied the men with underage prostitutes.

Good Friends: “James M. Curley, Mayor of Boston, is shown with Democratic presidential candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt during the presidential campaign in Groton, Mass., near Boston, Oct 30, 1932. Curley seconded Roosevelt’s nomination at the Democratic National Convention.” From Boston Herald.

Corrupt Boston politician Mayor Curley was the intermediary between the Movie Moguls and their extortionists, lawyer Daniel Coakley (who enjoyed long-standing Roosevelt support) and Nathan Tufts, the Middlesex County District Attorney. The Coakley/Tufts duo, like Charlie Chaplin’s gang, had made an art of the “badger trap” shake-down. Zukor and his crew paid Coakley and Tufts at least US $100,000 to keep quiet, but the pressure wasn’t released on Zukor until around 1921. In the meantime, Zukor put his Hollywood resources to good use during the Roosevelts’ war (WWI) on a committee that was run by one of Flo Ziegfeld’s early investors and President Wilson’s anti-porn Tsar…

Motion Picture Herald, March 28th 1942

You see, in the 1910s Jewish organized crime was far more likely to be pro-German because these gangsters’ leaders enjoyed such a close relationship with families like the Hapsburgs and Hohenzollerns. The money which paid for German imperialism was very often shepherded by high-level Jewish (Galician Gang) organized crime figures. The early film industry was financed by pro-German bankers at Kuhn, Loeb & Co— that is, pro-German until German Europe was no longer a suitable host for the supermob. The Kennedys used pedophilia to overcome Galician Gang pro-German sentiment until German Europe’s economy could be hobbled by WWI.

The Kennedys play a fascinating role intermediating between Galician Gang and Lincoln financial interests. Radio Corporation of America (RCA), the entertainment investment of Hayden, Stone & Co’s chief clients (General Electric, Westinghouse, AT&T Corporation and United Fruit Company), was handed to Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. in 1927, seven years after Kennedy took up running Hayden, Stone & Co.’s stock-trading desk in 1920. (A much busier position after the bucket shop competition was closed!) This 1927 hand-off was crucial to protect Lincoln financial interests from the 1932 anti-trust action from Kennedy’s bestie, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, when GE et alia were “forced to divest” from RCA. Divestment is not the same thing as losing control of an entity in the financial world, but clearly Kennedy organized crime was given a seat at Lincoln’s table.

Now I’d like to get into the nuts-and-bolts of how Hayden, Stone & Co. took down part of “Bossism”, the bucket shop industry. That’s no mean feat in 1906. I’ll start by pointing out that the bucket shops’ end began in Chicago, because the Lincoln men at the Board of Trade were tired of sharing and initiated a culture war against the bucket shops.

Below is a relic from that culture war. It is an image from Monroe, WI native Art Young’s retelling of Dante’s Inferno, titled “Through Hell with Hiprah Hunt.” It is a preachy image of bucket shop gamblers being tortured in hell. The hypocrisy is palpable.

Art Young, 1901.

“THE BUCKET-SHOP GAMBLERS. CANTO XLII. In what is called the Carousal of Hell, Mr. Hunt sees the long-legged devils. Some of these have legs thirty feet long. They hop about, chasing victims, in a game of tag. The feature of the game that makes it interesting for the devils is that they are never it. People who jump at conclusions are some of the unfortunates who are kept dodging and guessing in this department.”

Art Young’s father, Daniel Young, was a functionary of Arabut Ludlow, the Kentucky Colony’s counterfeiting lieutenant across the Wisconsin boarder. Therefore, Art Young’s dad was subordinate to the Chicago Skakel family who dominated the bucket shop trade under Bertha Palmer and her Kentucky Colony confederates.

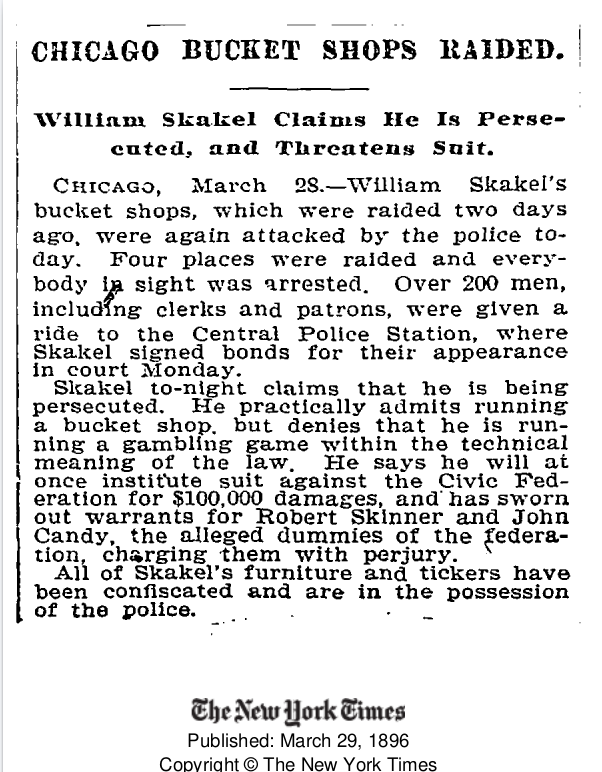

William Skakel was Chicago’s bucket shop don, and the great uncle of Ethel Skakel Kennedy, Robert Kennedy’s wife. (Robert Kennedy was Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.’s son.) Besides gambling, William Skakel ran bordellos and saloons. William raised Ethel’s father Curt, who struggled with alcoholism. If you’ve heard the name “Skakel”, it’s probably because the Kennedy cousin William Michael Skakel, William Skakel’s great-great nephew, murdered Martha Moxley in 1975.

Who were the Skakels? The demographic pattern of the surname seems to be of Scottish origin (like Monroe’s Latta and Banta families), with immigration to Canada, Virginia, Illinois and South Dakota. According to biographer Jerry Oppenheimer (who gives no sources) they were radical, bigoted Protestants, yet they married into families of drunks, slave-owners, inn keepers and womanizing “blacklegs”. That’s a remarkable combination. If true, these unusual dynamics suggest very early lower-class Jewish immigration to the New World, as discussed in When Scotland Was Jewish. (Protestantism was an attractive “cover” for quasi-assimilated Jews prior to toleration laws in the late 18th century; criminals of all kinds would run to wild parts of the New World to escape justice.) What we can say for sure is that the Skakels and their in-laws were comfortably apiece with the pre-1890 native criminal class.

The Skakels were far more like Abraham Lincoln than they were like Lincoln’s well-heeled Boston financial supporters, to whom Art Young pandered with his cartoons. New Englanders such as Prudence Crandall would have looked down her nose at whiskey dealers like Lincoln prior to 1848, when international newspaperman Horace Greeley met Lincoln in Washington D.C. Fast forward to the 1890s and Lincoln’s trashy baggage might be fine for his telegraph operators at Western Union, but not the Boston Brahmins at Hayden, Stone & Co.

Let me explain the character of Western Union and its short-lived contemporary companies: the early telegraph companies were sordid information brokerages. President Lincoln even collaborated with them to prostitute the Union’s military secrets during wartime. Over the course of the Civil War, Western Union absorbed all of its competitors as well as their illicit information trading. American criminals largely took example from Austro-Hungarian criminals (Galician Gang) in this regard and newspapers became Western Union’s partners-in-crime as financial intelligence clearing houses.

The telegraph office of Vienna’s Die Zeit newspaper, financed by rich Ringstrasse investors who benefited from Galician Gang human trafficking. This information brokerage and newspaper were bought by Archduke Franz Ferdinand with Rothschild money at around the time Hayden, Stone & Co closed Boston’s bucket shops in 1906. Franz Ferdinand would be shot by a political terrorist in Sarajevo a few years later and with him went the last powerful political resistance the the Ringstrasses' war designs in Eastern Europe.

Bucket shops were able to afford telegraph connections to the major exchanges because Western Union encouraged their business accounts. (In 1904, about half of Western Union’s income came from speculative trading like bucket shops!) In a sense, Western Union played an intermediary role between high organized crime and low organized crime, much like the Kennedy family intermediated between Boston’ Lincoln financiers and the Galician Gang.

The Chicago Board of Trade fired the first shot, with a series of raids on Skakel over the 1895-96 period:

The Chicago Chronicle, April 11 1896. Note the names of the keepers.

This harassment made Chicago increasingly uncomfortable for men like Skakel, the CBoT won their 1903 case, and the center of gravity for the industry moved to Boston. (Bear in mind that by the 1890s prostitution was more valuable to Chicago’s Kentucky Colony than any form of gambling.) With the ball in their court, two Massachusetts senators and the governor introduced legislation in Boston aimed at closing bucket shops for good. This troika included two Massachusetts Volunteer Militia men (the MVM was Hayden, Stone & Co’s nursery) named Senator Edward Lawrence Logan (a Democrat after whom “Logan Airport” is named) and Governor Curtis Guild Jr. (A progressive Republican and good friend of Theodore Roosevelt.) The third wheel was Senator James H. Vahey, a Democrat Irish Catholic labor organizer who had just been elected to the senate. The bill was handily defeated by sound arguments…

The Boston Globe, May 2, 1906. Page 6.

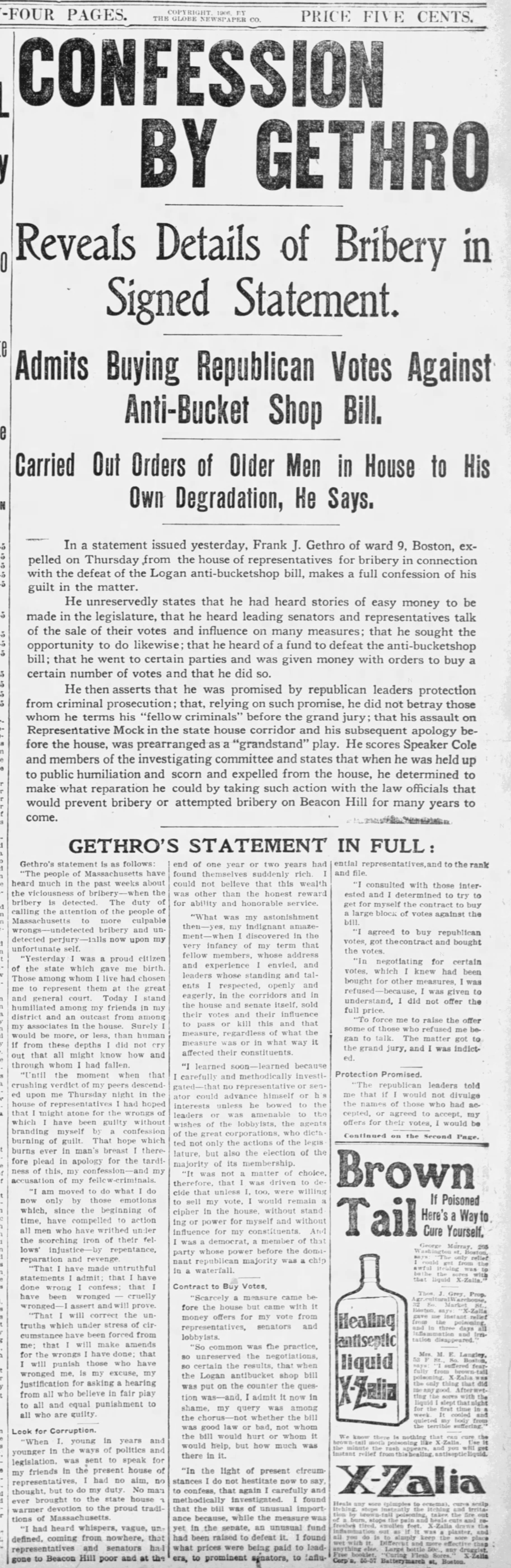

Here’s where Coakley’s hand can be seen— a hand holding that of Hayden, Stone & Co. Because the bill was defeated, it had to have been defeated unfairly, right? Bucket shops were accused of bribing house members through a “boodle agent”, and Coakley participated in the corruption investigation alongside Hayden, Stone & Co. men.

Boston Evening Transcript, June 6, 1906.

As if on cue, Coakley’s client Representative Gethro (a man from Lincoln’s party of course) committed seppuku by printing a public admission of his nefarious deeds:

The Boston Globe, June 24, 1906 1/2

The Boston Globe, June 24, 1906 2/2

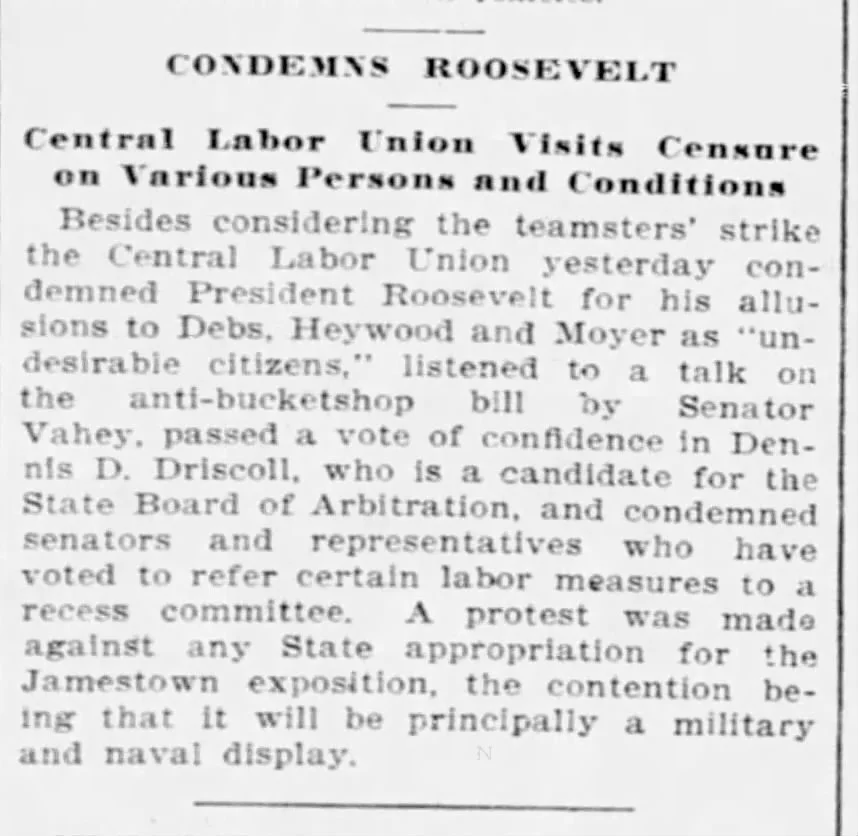

Once confidence in the honesty of the vote on the Anti-Bucket Shop bill had been eroded, the work of setting up a second vote could begin. Senator Vahey got busy explaining to union men why working people should have fewer investment opportunities. These union men were typical Boston Kennedy-ticket voters.

Boston Evening Transcript, April 8, 1907.

… and lo and behold, when the second round of the Anti-Bucket Shop bill came to vote, Massachusetts legislators got it right this time!

Boston Evening Transcript, June 18, 1907.

Hayden, Stone & Co. were now in the clear to absorb that portion of the bucket shop patrons’ market which they could make profitable. The history of the financial community shows such profits were not easy to make before computers, however a young Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. was summoned from his job at the Fore River Shipyard to work at Hayden, Stone & Co’s stock trading desk in 1919:

The Boston Globe, July 3 1919.

The Boston Globe, July 2, 1920.

That Joe would slither to Hayden, Stone & Co. from the Fore River Shipbuilding company just after the Great War had me laughing out loud, readers. Does anyone remember Monroe movie theater doyen Leon Goetz’s non-existent submarine patent? Or the Mormon skullduggery trying to sell battleships to the British? Or Teddy Roosevelt’s American Shipbuilding Company that built submarines for the British in the Great Lakes circa 1909-16 in violation of US neutrality? Well, Fore River Shipbuilding is where the Electric Boat Company built the US Navy’s submarines, and EBC was the source for “American Shipbuilding Company’s” submarine expertise. Fore River Shipbuilding was founded by Lincoln telegraph man Thomas A. Watson, who we met a few weeks ago as a founder of the Boston Lincoln financiers’ AT&T. Warships and communications, readers.

Remember Edith May’s post-WWI bawling about “battleships” and socialized charity for William Wesley Young and his patrons the Guggenheims and Seligmans? I do.

As Europe slid into war in 1913, Charles Schwab’s Bethlehem Steel bought the ASC’s brain trust Fore River Shipping. Schawb’s interests were seen as broadly aligning with Imperial Germany’s and contrary to those of the Roosevelt Family. In fact, Schwab was also on the board of the Empire Trust, which alongside Austrian financiers Kuhn, Loeb & Co, had supported Thomas Edison’s film monopoly the Edison Trust. At some time during Schawb’s ownership of Fore River during WWI, Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. was put in charge as vice president. I’ll mention that Elizebeth Smith, the NSA mother, said rum-runners (like Joe Kennedy Sr.’s family) used the same encryption codes as German military intelligence. She should know, ’cause she worked for Prussia too before WWI.

My sense is that this is enough information for one post, but readers I look forward to what other Monroe, WI Early Film Mysteries will be solved by the history of Hayden, Stone & Co.