Lincoln and the Rothschilds

The Boston investors behind Abraham Lincoln’s political career set up a firm, “Hayden, Stone & Co.”, to broker their railway and telecommunications investments. The investors had wrested control of these assets using their political power after the Civil War. Readers will know these telecommunications companies as “Western Union” and “AT&T”. But HS&C had other investment interests too, particularly copper mining, at a time when the influential Rothschild family were committed to cornering the global copper market.

In this post I’ll look at HS&C’s development of American copper resources and compare that to what we know about the Rothschild’s curious investment strategies. I make a strong yet circumstantial case that Lincoln’s Boston investors worked with the French and English branches of the Rothschild family to get ahead of their domestic and Imperial German competition in the copper extraction business. In the case of Utah (Mormon) copper, the agent who the Rothschilds used to do this was a man from Ziegfeld Follies costumier Lucy Duff Gordon’s circle.

Lucy Duff-Gordon created a lingerie business that was financied by her unorthodox investor husband, Cosmo Duff Gordon. Her expensive undergarments were sold to the nouveau riche and high class prostitutes. LDG undies were what the Everleigh Sister’s prostitutes would have bought at Marshall Field’s department store in Chicago. When the bloom had fallen from her lingerie career, LDG went downmarket to costume Flo Ziegfeld’s NYC sex show. (See my post on Monroe’s Ziegfeld girl Edith May Leuenberger and LDG.)

From the 1840s, Boston financial interests dominated copper mining in the United States. The national press adopted the term “Boston Coppers” when reporting on these firms. Hayden, Stone & Co were the semi-official press mouthpiece for the “Boston Coppers” from the 1890s.

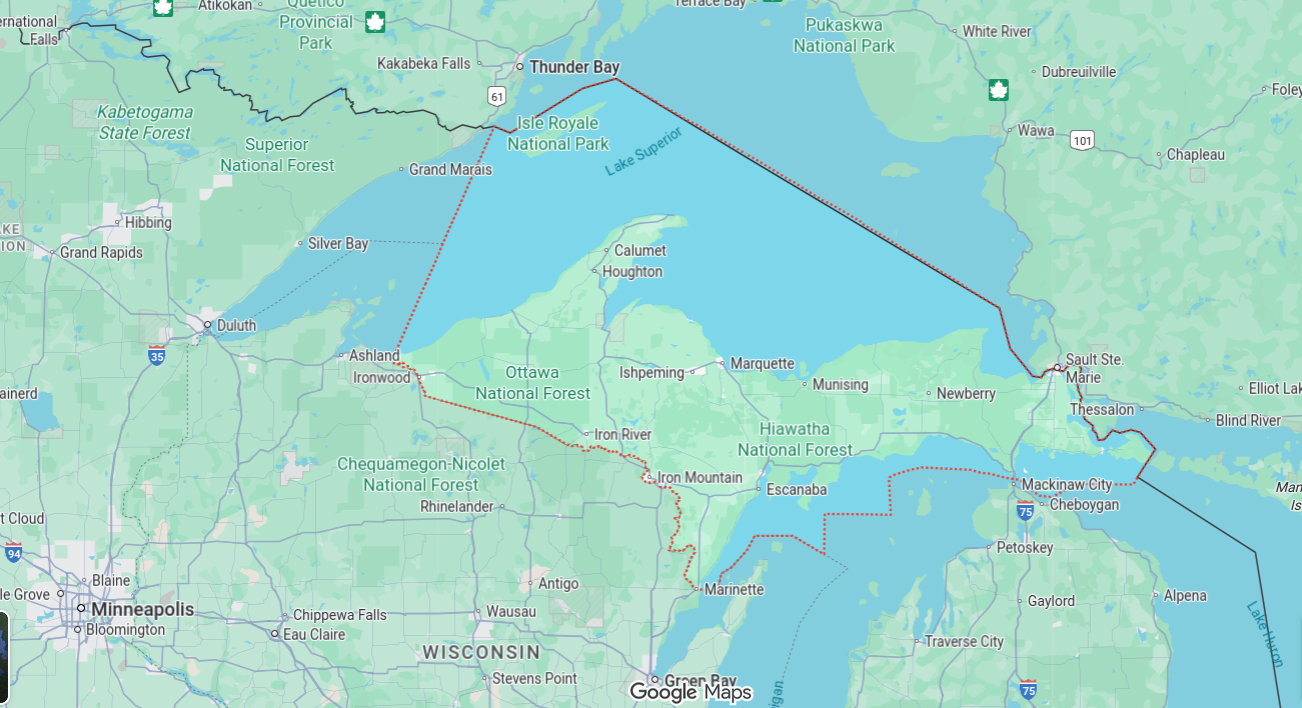

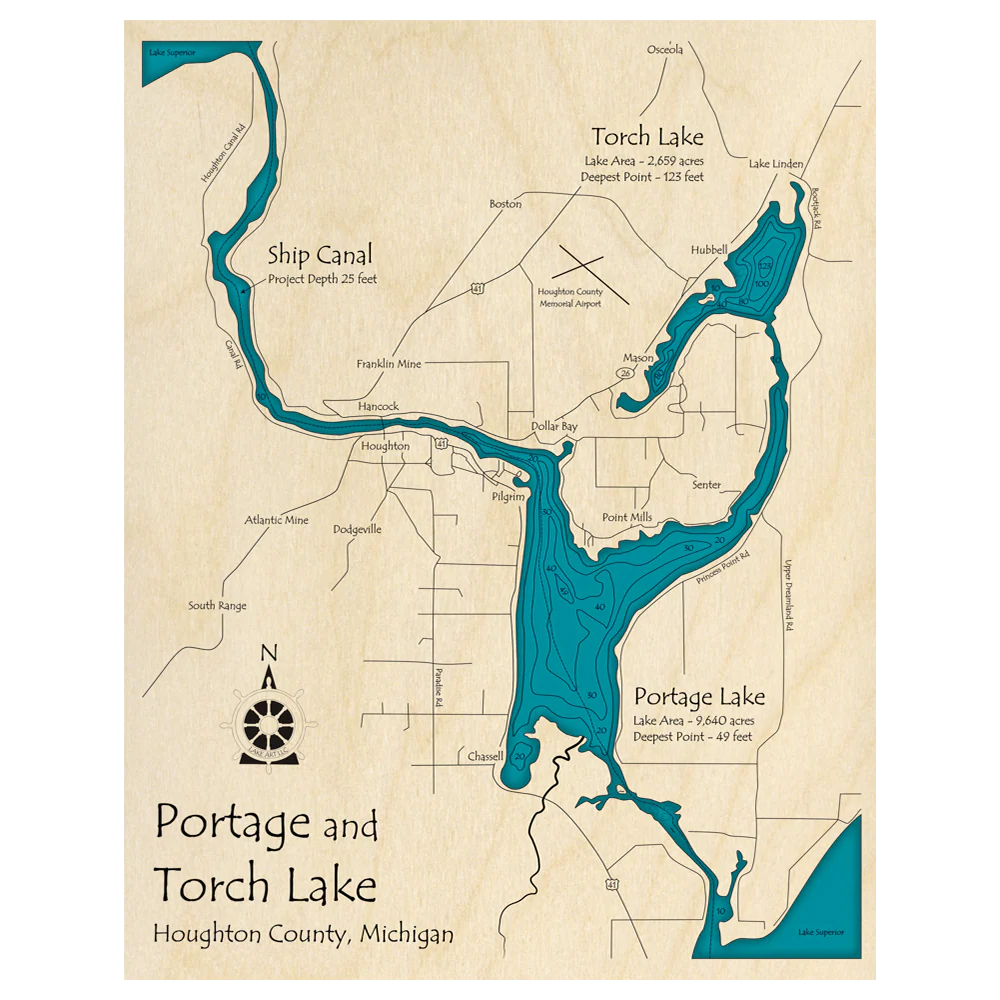

Which companies made up the “Boston Coppers”? The first were located in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula, which is a tongue of land that extends out from the top of Wisconsin and into the Great Lakes. This UP ore had a low arsenic content which made it ideal for electric wires. The earliest of these UP mines was named “Quincy” (like Quincy, Massachusetts, home to the presidential Adams family). The Quincy Mining Company provided the North’s copper for the Civil War.

The Upper Peninsula of Michigan is actually part of Wisconsin’s land mass and is marked out by the dotted red line in the map above.

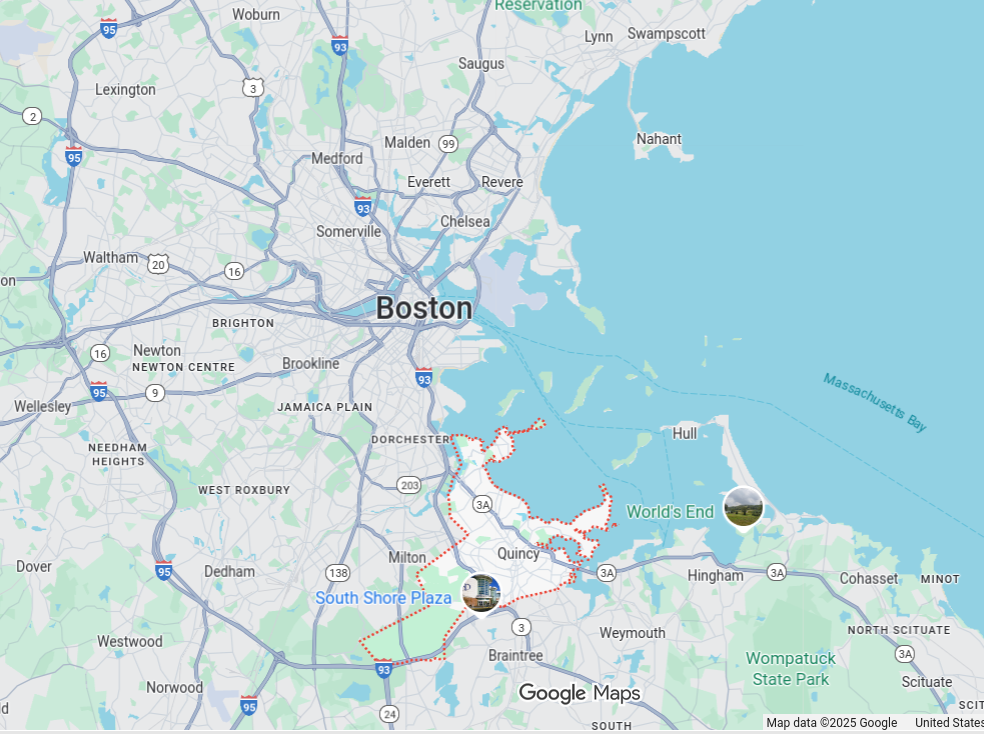

In 1840 Quincy was its own separate town, but it has since been absorbed into the Boston sprawl.

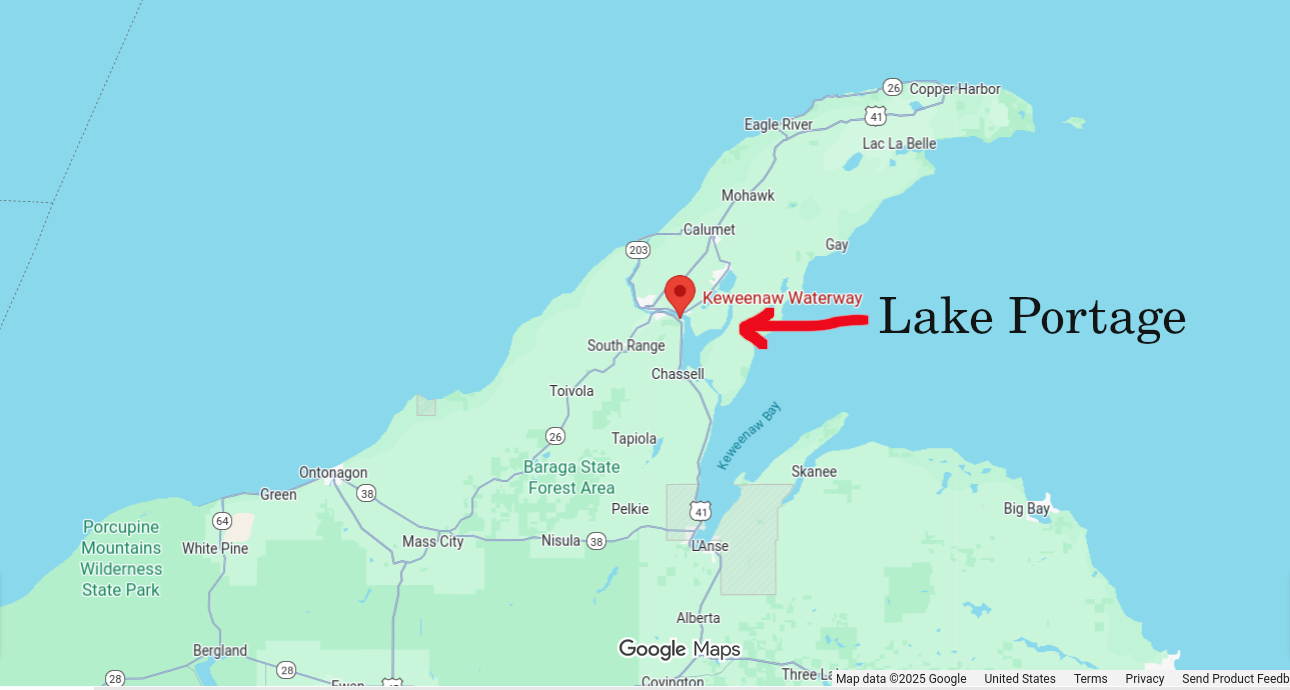

After the Civil War, the Quincy Mine was overshadowed by the operation of Quincy Adams Shaw, a wealthy man from an abolitionist Boston Brahmin family. Quincy Adams’ company was named “Calumet and Hecla Mining Company”. Calumet ended up controlling copper mining north of Portage Lake and took over the neighboring Tamarack (1917) and Oceola (1909) mines too.

The northernmost tip of Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. (Note the location of Calumet on the first map.)

Remember MVM doyen John Albion Andrews’ imported black militias, the Massachusetts 54th and 55th regiments? Quincy Adams Shaw’s nephew Robert Gould Shaw was one of the white officers whom abolitionists prevailed upon Andrews to appoint as leader of these black regiments. Robert Shaw was shot before he could become disillusioned with the cause like Andrews. The Shaws were Unitarians, a nominally Christian sect which, like Muslims and Jews, denies the Holy Trinity and whom I wrote about with respect to their involvement with the Ottoman (White) Slave Trade here.

South of Portage Lake, copper mining was controlled by another Boston Brahmin, William A. Paine of brokerage “Pain, Webber & Co”. Paine’s firms were Lake Copper Company and Copper Range Consolidated Company. After Lincoln, the choicest copper in Michigan was solidly in native Boston hands.

So there’s nothing very surprising about what I’ve just described. Lincoln’s Boston men won the Civil War and to the victor go the spoils. Things start to get a little weird in the late 1870s, however.

In 1878 AT&T president Theodore Vail decreed that copper would be used for the firm’s telephone and telegram wires, so naturally copper mines were a favored investment for Hayden, Stone & Co. when the brokerage was founded a little over ten years later. (Theodore Vail was made AT&T’s D.C. godfather by Boston Brahmin Gardiner Hubbard, the eminence gris of early American telecommunications. Hayden, Stone & Co was founded under the patronage of MA Governor Crane, the largest single AT&T stockholder at the time.) AT&T’s choice of copper guaranteed decades of strong domestic demand.

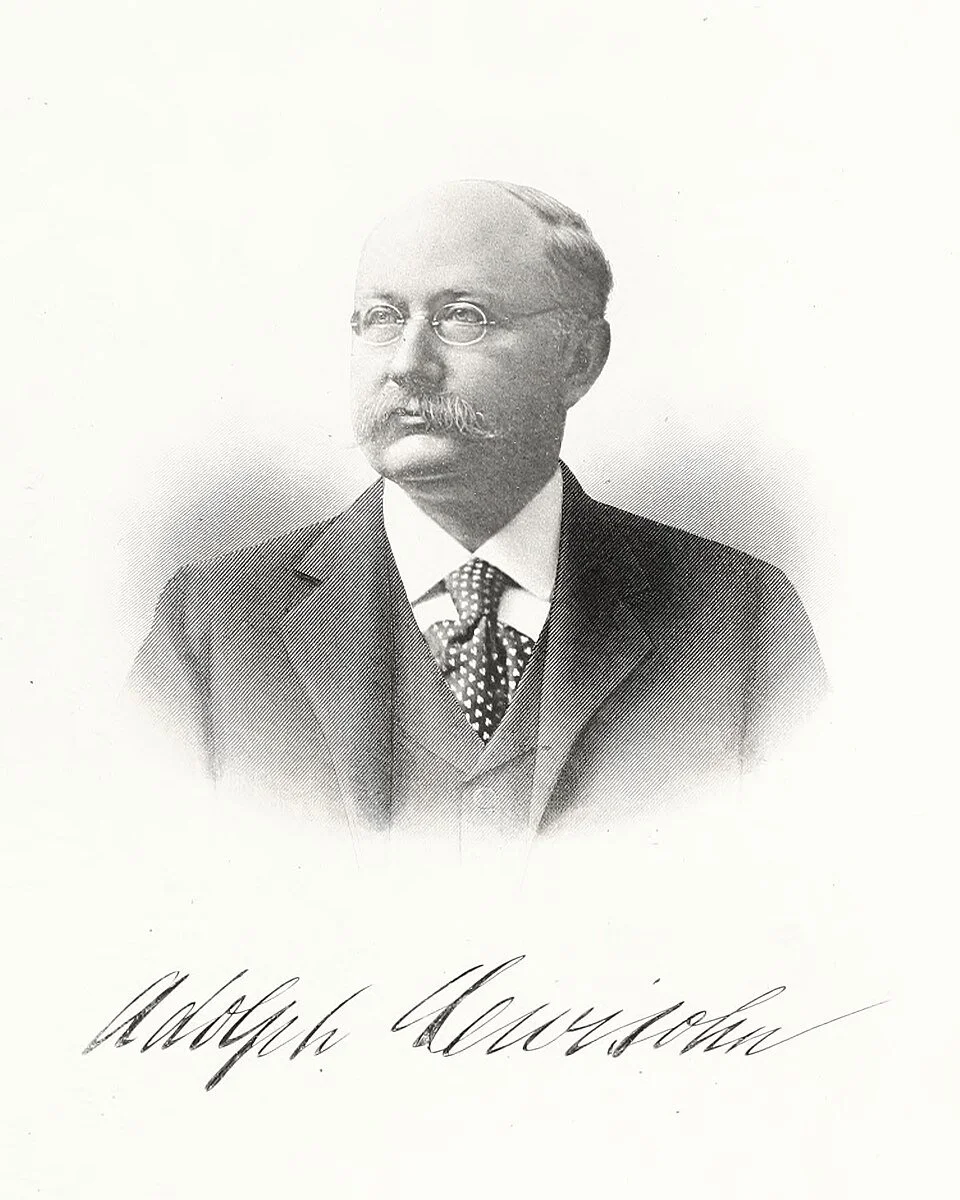

Also in the late 1870s the Rothschild banking family went through some dramatic changes. Central Europe was in recession, largely because of Hapsburg economic favoritism to families like the Rothschilds and their clients who were neither far-sighted nor ethical investors. (Often quite traitorous, too.) The Rothschilds’ big pre-1873 bet, state-subsidized railway investments, had been pumped-and-dumped and now they needed something new. [I wrote about these railways with respect to LDG’s sister, Elinor Glyn’s banker-inlaws.] The third generation of the Rothschild family, cousins like Anselm Salomon von Rothschild (Vienna), Lionel de Rothschild (London), Alphonse James de Rothschild (Paris) and Adolph Carl von Rothschild (Naples) decided to corner non-ferrous metals markets for their next big win. (Portraits in listed order.)

The Rothschild’s Central European “Karl-Ludwig Bahn” railway stood little use beyond human trafficking for the Galician Gang, which the Rothschilds were remarkably ineffectual at countering.

This copper-corner dream was a complicated undertaking for the Rothschilds. The family had made money and enjoyed privilege as war financiers to European heads of state. In that situation they couldn’t be seen squeezing struggling European industry by cornering metal markets, especially since they’d just emptied national treasuries through railway scams. A certain amount of finesse was needed. The family developed ways of hiding their involvement in market-corners.

The Rothschilds did not like open investment in US assets, they preferred to work behind agents (like August Belmont); or hide their involvement behind secrecy agreements such as those which protected Queen Victoria’s financial dealings; or hide their control behind groups of smaller shareholder “partners”. As explained by economic historian Jose M. O’Kean [“Rothschilds’ strategies in international non-ferrous metals markets 1830-1940”, Economic History Review, 67, 3 (2014), pp. 720–749]:

The real [Rothschild] control of these firms was obtained through packets of non-majority shareholdings, which conferred considerable control because other holdings were dispersed or controlled by partners (table 2).

This secretive tactic was part of a larger Rothschild Family strategy to “to control the international markets of four products: mercury, lead, nickel, and pyrites (copper and sulphur).” They had a functional monopoly over the gold market too via their control of the London markets and later “Gold Fixing”, a position they achieved through war financing. Secret ownership lessened the threat of government regulation and hid conflicts of interest with their other main business, lending to governments.

Dr. O’Kean makes another important point about collusion, rather than competition, resting at the heart of the Rothschild strategy:

In order to exercise their market power effectively, the Rothschilds would directly acquire ownership and control of mines using their own financial reserves and taking advantage of the needs of government treasuries or owner companies that needed their financial collaboration. This was done by all sorts of corrupt practices as they acted more as financiers and profit seekers than as entrepreneurs. Continued control of the companies was implemented through contained business capital issues, while never seeking to merge all their mining interests, since it was never their aim to create huge mining corporations but rather to have sufficient representation in the markets to go ahead with non-competitive collusive agreements with the competition as required. They were always wary of competing with other producers, preferring to collude in raising or holding market prices above the cost margins and so obtaining extraordinary profits and attaining neo-monopolies whenever possible.

The “non-competitive collusive agreements with the competition” which O’Kean describes is the same strategy used by the Beef Trust families: Armours, Cudahays, Swifts. It was only because the other beef families died off that J. Ogden Armour was left with control of the syndicate.

So now that we understand what the Rothschilds were about, let’s look at the post-1870s developments in the US copper industry. The next “Boston Coppers” came from Montana and Utah, but instead of being purely Boston affairs, German Jewish financial involvement was prominent. In Montana, it was the Lewisohn Brothers.

The Lewisohns— Adolph and Leonard— were from a well off Hamburg family of international boars’ bristle merchants. This in itself is interesting, because it was Jewish boar bristle merchants who formed the most violent cell of radicals during the Russian Revolution. It was they who spread the Bolshevik gospel and did the wet work. Ultimately the fruits of their labor would have been sold by the Lewisohn family out of Hamburg. The following information comes from “Class Struggle in the Pale” by Ezra Mendelsohn [Cambridge University Press, 1970, p. 72]:

The Bristle-makers Bund was a "kassy" [trade union] “Bershter-Bund” that had exceptional networking privileges outside its local craft and geographic area. They were “the cream of the crop of our movement” according to organizer Medem. They worked in small towns along the Prussian border, they smuggled into Russia illegal literature and trafficked revolutionaries. The Jewish Colonization Association (de Hirsch and Rothschild) were very interested in these bristle-makers, and considered them more intelligent and cultivated than other Jewish worker groups. By enlarge most had middle class (shop-keepers and merchant) origins (like the stocking makers). They published their own newspaper, “The Awakener”, and organized across cities. This was the only single trade which had chapter organizations across many cities.

Note that the bristle-merchants in question were Polish Jews who emigrated to Russia after the Partitions of Poland (1772-95), yet the lingo is German-derived. Strange cosmopolitanism, no?

Jewish Bund election poster from Kiev, 1918. "Where we live, there is our country!" Galician Gang traffickers— whose business often overlapped with that of the Bund members— would partner with imperial secret service organizations to sell information on nationalist movements. Sometimes the Galician Gang would be hired to beat up the Bund terrorists/vigilantes too. Bloods n Crips.

In NYC the Lewisohns carried on the same bristle trade until competition from the Beef Trust torpedoed their profits. For some reason in the late 1870s the brothers decided to swap to copper trading instead. Instant volume, instant success! By 1878 international copper trading was their main line of business.

From my favorite German Foreign Ministry website, ImmigrantEntrepreneurship.org:

In 1879, they [the Lewisohns] acquired their first copper mine in Butte, Montana. Founded as a settlement of gold miners, Butte soon became famous for its enormous quantities of copper. Known as “the richest hill on earth,” Butte flooded the U.S. market with copper in the following decades. The first claim the Lewisohns acquired there was called “Colusa;” its previous owner was Charles T. Meader. To work the claim, they founded the Montana Copper Company with start-up capital totaling $75,000 (approximately $1,690,000 in 2010). While the purchase price was attractively low, the risks and problems lay elsewhere. First, Butte had no railroad connection.

Fortunately— fortunately— the Lewisohns had great contacts with Lincoln’s railway, the Union Pacific. The nice men at UP built Adi and Lenny a line so they could get their copper out East. The nice men from Northern Pacific RR and Great Northern RR then did the same, but for less money:

To solve the transportation problem, copper producers in Butte prevailed upon Union Pacific to build a railroad connection from Ogden to Butte. The first train reached Butte at the end of December 1881. his, of course, was good news for the producers, but since Union Pacific now had a monopoly on the line, their costs still remained high. Fortunately, in 1884, Northern Pacific built a connection to Butte as part of a new line that stretched between Helena, Montana, and the West Coast. The second line created competition and drove down prices, and also made it possible to move freight to San Francisco, Seattle, and Portland, Oregon.

The Lewisohns negotiated with Northern Pacific to secure a favorable transport rate. The downside, however, was that this rate was contingent upon their guarantee of a large volume of freight. They realized that they could only generate the necessary volume by utilizing the less copper-rich ore that their mine was producing in large quantities. So while they endeavored to deliver the volume needed to uphold their deal with Northern Pacific, they also worked another angle and tried to persuade James J. Hill of Great Northern Railway to build a line to Butte as well. They ultimately succeeded, and Great Northern reached Butte in 1888. The Lewisohns were able to negotiate even lower rates with Great Northern, but Hill also demanded high volume guarantees.

The Lewisohn’s cooperation with the Northern railways lead them to have such great success that the brothers were edging in on Michigan copper’s market share (down from 80% to 53%), even though the quality of the Montana ore was inferior. This hurt the Boston investors. Did the Lewisohns keep trying to out-compete the “Boston Coppers”? No! They colluded with them:

The Lewisohns were successful as copper producers but above all as copper traders. All three of their business activities – mining, processing, and trade – developed in tandem. As early as 1885, they were active as sales agents of the “Tamarack,” “Osceola,” and “Kearage” mines on Lake Superior. In 1887, they entered into a partnership with the mines’ owners, Joseph W. Clark and Albert S. Bigelow of Boston, and set up the Boston & Montana Consolidated Copper and Silver Mining Company (B&M), as well as a small subsidiary, the Butte & Boston Consolidated Mining Company (B&B). Lewisohns (Leonard, Adolph, and their half-brother Philip) were active in both companies, and the partnership offered financial securities for the building of the smelting works at Great Falls.

Thanks to its superb management and solid financial reserves, B&M became the largest company in Butte alongside Anaconda.

And there’s the rub: the Anaconda mining concern. Founded by Irish immigrant Marcus Daly in 1881 this company used money from John William Mackay— the guy who financed Lincoln-telegraph-boy Albert Chandler’s hot revenge on Western Union: The Postal Telegraph Company. Other financiers were George Hearst (William Randolph Hearst’s dad) and partners James Ben Ali Haggin and Lloyd Tevis. Later, the Heinze brothers would come in to support Anaconda. Readers will note these names would be Roosevelt’s enemy list in a decade. Naturally, Anaconda was a threat to the Rothschild’s copper-corner.

In 1892 the French Rothschilds began negotiations to buy the Anaconda mine. In mid-October 1895 the French and British Rothschilds bought out the stock in Anaconda held by Hearst's widow, Phoebe Apperson Hearst, who was a suffragette and schoolteacher who promoted the Ba’hai faith. A sorta proto- “Tech Mafia” wife. This Rothschild share would not have been a majority share, but it may have been a controlling share depending on the firms’ debt structure.

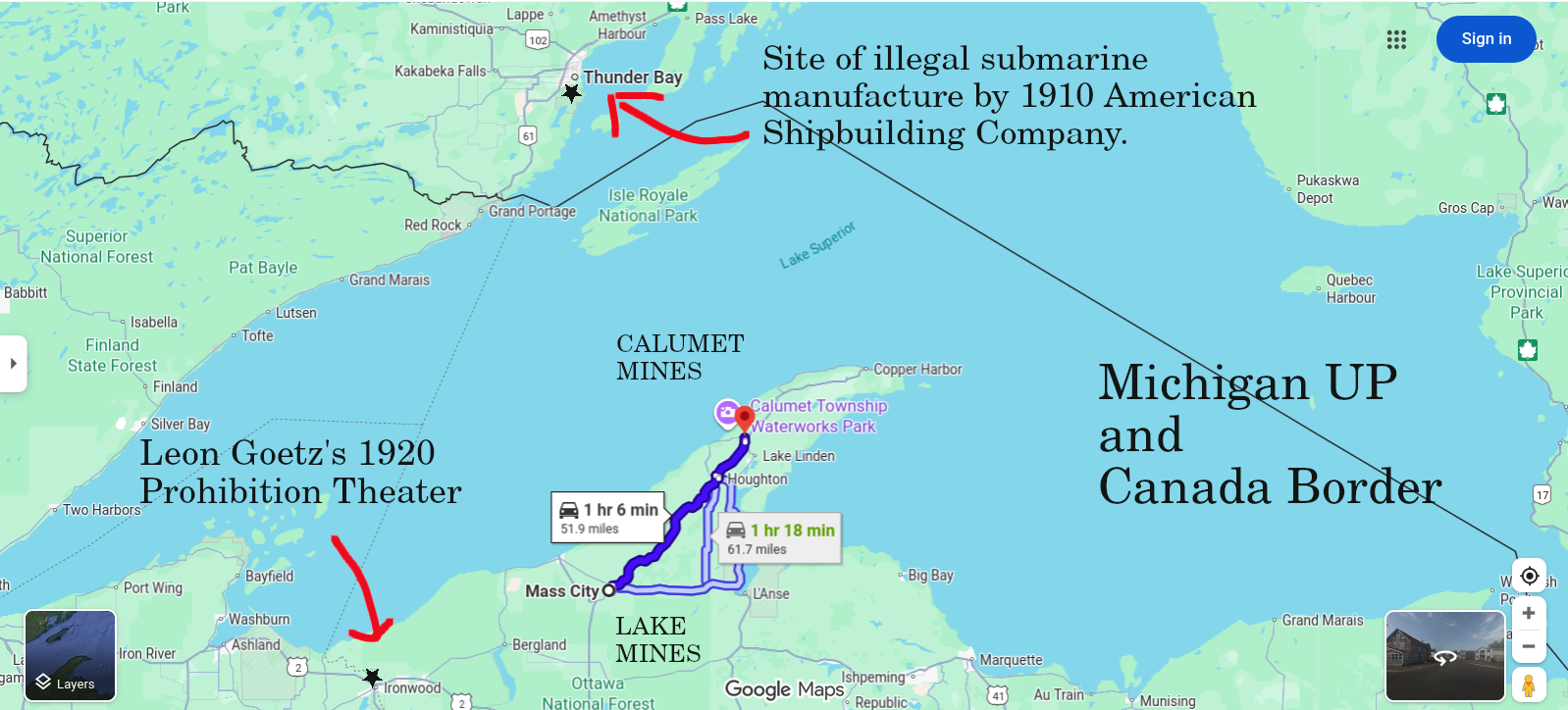

The Rothschilds didn’t like to own things outright, though. Four years later, in 1899, the Rothschild’s investment partner in Anaconda, Marcus Daly, brought in William Rockefeller who had a very similar outlook on competition as the European family. Thereafter Anaconda, soon renamed the Amalgamated Copper Company, was publicly associated with the Rockefeller Family and their Standard Oil capital pool— though it is not known if the Rothschilds divested or decreased their control. To do so would have been to give up on their corner. So much for the Montana “Boston Coppers”.

Let’s talk about Utah next. Brigham Young distrusted the Lincoln men and the mining developers. They brought in a large workforce of people who were not Mormon, and often criminally inclined. With the laborers came competing bordellos and saloons— none of which would have kicked upward to the saints. Frankly, after the Civil War, there was precious little Brigham Young could do about the Lincoln Men’s relentless march West.

The Boston Coppers in Utah start with a silver mine, the Jordan Mine, which was opened by a Civil War general named P. E. Connor. It worked a stretch of ore in the Bingham Canyon, named after the Mormon Bingham family, who were lieutenants to Brigham Young. The Jordan Mine came under control of one Liberty Emory Holden, a Lincoln man and literature professor from Maine by way of Ohio, who also operated the “Telegraph” mine. Holden operated these mines for a “group of other Ohio and Michigan investors”; shortly he would go into the newspaper business with Joseph Medill of Chicago and Mark Hanna of Ohio, the illegal submarine merchant.

Lo and behold! In 1879 Holden sold the Telegraph company to “a French company at a great profit, and used the proceeds to buy other mines in Utah and the West.” Another Utah Mine, the Franklin, would be sold to British investors in 1890. Within ten years Holden’s son, Albert F. Holden, controlled all three as the “United States Mining Company”. Over the next few years Albert Holden’s US Mining went on a buying spree in the Bingham Canyon represented by “a group of Boston investors”. British…French…Boston…British….French….Boston….

At the same time Boston, British and French investors were cashing in on the Mormon Church’s weakness, a scrappy young Jewish immigrant from Europe by way of NYC found his way to Salt Lake City. Samuel Newhouse was more interested in running hotels than mines, and he quickly became a millionaire running a hotel in the rough mining town of Leadville, CO with this wife, the daughter of a “boarding house” keeper. In rough mining towns like Monroe, WI or Leadville, CO, “running a boarding house” was often a euphemism. With minimal mining experience, Newhouse became agent for a consortium of London investors after meeting one of their agents at his “hotel” business. This agent was most likely Barney Barnato. Who was he?

The Herald Democrat [Colorado], December 17, 1895

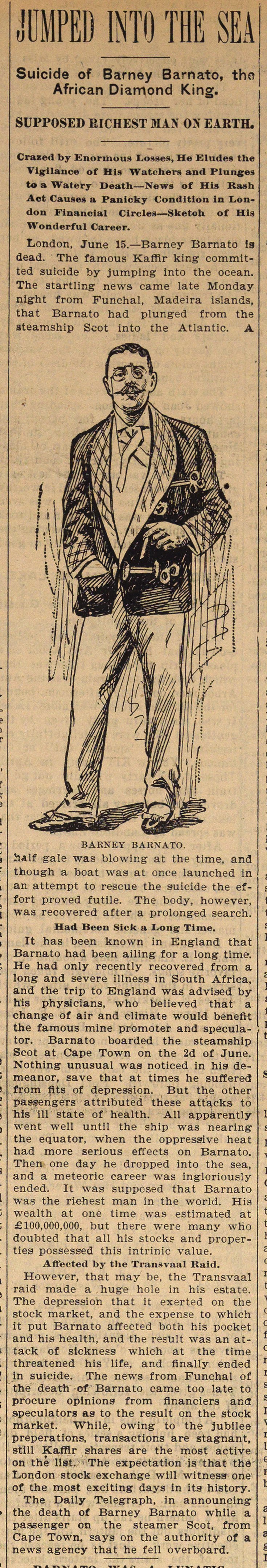

Barnato was a Jewish man from London’s infamous Whitechapel District. The son of a rag merchant, Barney became a prize fighter like David Belasco, then went to South Africa to get in on the diamond mine rush. Where did the money come from? Barney Barnato’s career path was typical for London-based Galician Gang members and, once in South Africa, Barnato got into business with Cecil Rhodes of the Lucy Duff Gordon set. With Rhodes’ patronage, Barnato became the top shareholder in De Beers Diamond Mining Company. Quite literally from rags to riches.

Barnato, caricatured by Spy in Vanity Fair, 1895

In 1895 Barnato was tasked with investing those diamond profits into Utah copper. Together with Newhouse, they founded the Boston Consolidated and Utah Consolidated mining companies. More Boston Coppers!

Back in Boston, Sam Newhouse had a tight relationship with Hayden, Stone & Co. The newspaper clip below is from 1907 and shows that Newhouse served alongside HS&Co on the board of a Canadian silver mining concern in Cobalt (town), Ontario. There were dozens of Boston brokerages but Newhouse and the Canadians decided to crawl into bed with Charles Hayden.

The Boston Globe, January 17, 1907. Nipissing was a Canandian company. My guess is that CIA/OSS/BSC mastermind William Stephenson’s secret fortune came from pretty near here. Oh, Canada!

Within a year of partnering with Newhouse, Barnato would lose all his money when South African gold mine share prices collapsed in 1896. The Rothschild Family (English side, N M Rothschild & Sons) were the major players in Imperial Britain’s gold market by this time. Just like Robert Maxwell, Barnato fell into the sea a few months later.

Ann Arbor Argus, June 18, 1897. It was this or be pushed under a locomotive. Which would you chose? Have fun with “Kaffir”.

Things didn’t go well for Newhouse, either:

Newhouse’s extravagant spending projected the end of an era. Many of his mining properties did not yield enough capital to justify the work on his decadent projects and lifestyle. When World War I broke out, this only complicated matters as it was much more difficult for Newhouse to obtain loans from Europe and Eastern states in the U.S.

WWI was bad for the Galician Gang too because passport controls made trafficking harder and the money dried up.

Newhouse’s wife divorced him when their money dried up and in 1930 he died living with his sister in Paris. Much like William Stephenson’s intelligence community, Newhouse’s patrons were great users of people.

But Newhouse’s poor management opened up opportunities for… the Rockefellers and Lewisohns! In 1888 Henry H. Rogers and William Rockefeller (the Standard Oil guys from the Rothschild’s Anaconda investment) and Adolph and Leonard Lewisohn (the Bund Bristle Kings from Boston & Montana Consolidated) teamed up to form “American Smelting and Refining Company”. Somehow the Swiss Jewish Guggenheim family got control of this partnership in short order and achieved the Rothschilds’ aim of a lead monopoly via a choke-hold on smelting.

“American Smelting and Refining Company Exhibit, Montana State Fair, Helena, Montana” 1905. Montana State Library.

In 1907, when Sam Newhouse took over directorship of Nipissing alongside W. B. Thompson, he was also in negotiations with Daniel Guggenheim who was president of “American Smelting Securities”. By 1906 the Guggenheims already owned a large interest in Newhouse’s Boston Consolidated company and by 1909 the Guggenheims controlled it.

So Newhouse, the “Colorado agent of the Rothschilds”, was open to letting the Guggenheims sail in and take over his business. Newhouse’s friends Hayden, Stone & Co. got in bed with the Guggenheims early too— right after HS&Co put their “bucket shop” competitors out of action. In fact, the Guggenheim partnership in New York silver markets was HS&Co’s first order of business after taming US commodities markets. (C. Schumacher & Co. were German international silver merchants who would disappear in a few months.) Clearly, Newhouse and HS&Co knew how to pick a winner because the Guggenheims achieved that massive copper corner fifty years after the third Rothschild generation had dreamed it up, controlling 87% of the copper market at their peak in the run up to WWI.

But wait! The Guggenheims achieved other Rothschild goals too: “By 1915, the Guggenheims controlled 75 percent to 80 percent of the world's silver, copper, and lead, and could dictate prices.”

In 1849 the Guggenheims were dirt poor charity cases in Aargau, Swizterland. Their habit of having/adopting more children than they could afford— and I mean a lot more— made them a drain on Aargau’s social services and their local municipality paid them to leave. While many cantons dealt with their poor this way— many of Green County, WI’s Swiss immigrant settlers came here with emigration association funding— to be forced out because of irresponsible reproduction/child-hoarding was remarkable. But by 1870 the Guggenheims were buying railroads and shortly thereafter achieving Rothschild-scale market corners. Makes you wonder, doesn’t it?

The Guggenheims always had a very cosy relationship with Hayden, Stone & Co. Remember Newhouse’s HS&Co Nipissing partner W.B. Thompson? Well W.B. Thompson represented the Guggenheim family as well as Hayden, Stone & Co.:

Boston Evening Transcript, May 25, 1906 p. 6.

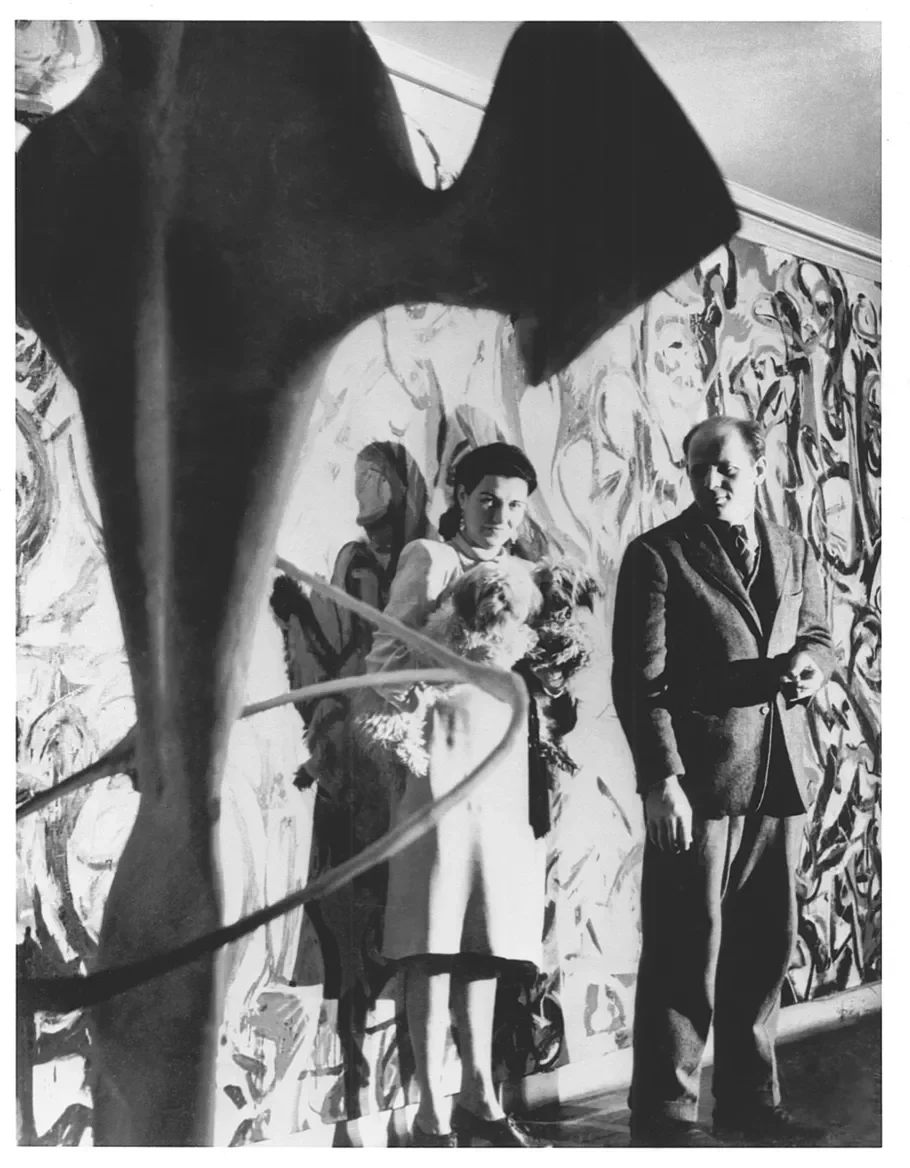

Interestingly, Guggenheim business ventures would disappear from press discussion at about the same times as those of Frederick H. Prince, Boston’s mayor-turned-banking magnate and Joe Kennedy Sr buddy whom I wrote about with regard to the Beef Trust. The next Guggenheim the public heard of was Peggy and her CIA-funded art boyfriend Jackson Pollock.

Peggy, Jackson and the CIA art.

Perhaps I get ahead of myself. Prior to WWI Hayden, Stone & Co. would work with the Guggenheims to fend of Imperial German investment in US mining concerns through the German-Jewish Heinze Brothers, who were great at using the Boston Coppers’ greed and arrogance against them in the press. This riled HS&Co on more than one occasion:

Boston Evening Transcript, February 3, 1906. Page 8. NB “Amalgamated” was the new name for Anaconda.

So there you have it. The Lincoln Men at Hayden, Stone, & Co. were buddy-buddy with Anglo-French Rothschild Agents— not hard to spot if one understands the Rothschild’s post-Grunderzeit/1873 investment strategies. My next foray into this topic will be examining Charles Hayden’s [Hayden, Stone & Co. founder] activities next to those of Otto Kahn, the Austrian Intelligence Agent, which ought to answer more questions about the history of Early Film in Monroe, WI.

Merry Christmas!