AT&T: Lincoln's Ringstrasse Information Bureau

One of my interests is the post-1848 newspaper “ecosystem” in Austria-Hungary. “An unsympatheic press” fermented the 1848 uprisings, as Field Marshal Radetzky astutely pointed out. Emperor Franz Joseph’s reaction was weak: he bought compliance from the press magnates, many of them wealthy Jews who came into money after Joseph II’s 1781 “Patent of Toleration”, by turning a blind eye to financial market manipulation printed in their newspapers. As long as these crooked magnates ransomed a vast cash sum and didn’t print news contrary to the Emperor, they could dupe his subjects in any manner they chose. This had disastrous financial consequences, but it also subsidized the creation of newspaper-informant networks like that run by Moritz Szeps. Vienna’s newspapers became political fronts for information-selling networks that predated professional spy services, what we might call the “intelligence community”. Often these networks had back-ends in organized crime and human trafficking.

Moritz Szeps was from a wealthy Galicia-based Jewish family. Under cover as a medical student in Vienna, he built an international informant network that was focused on Austria’s new trading partners in Eastern Europe and the Ottoman Empire. He knew Austrian military movements better than the Emperor’s General Staff, and counted Crown Prince Rudolf among his palace and Foreign Office informants. Most of his information of course would have come from Galician Gang pimps plying their trade around military bases throughout Europe. Szeps’ “journalists” came from a similar milieu:

It was at the Die Morgen-Post where Szeps developed the key to his success as a newspaperman: using advertising to subsidize an informant network. Szeps’ first “coup” reporting in 1885 involved coverage of the situation in Montenegro in the Balkans. Crown Prince Rudolf, who would become Szeps’s most valuable espionage agent in the Court and Foreign Ministry, noted that in the 1880s many of Szeps’s co-religionists served as military officers in the Balkans and were highly decorated—this was almost twenty years after the implementation of the Konkretualstatus [officer selection taken out of the hands of land-based nobility].

Szeps’ flagship newspaper was the liberal Morgen Post (1855-1967), followed by the Neues Wiener Tagblatt. In 1886 his financial backers, the Rothschilds and their client families, forced him out of editorship of the Tagblatt because of pro-French provocation against the Rothschild’s patrons, the Hapsburgs. Szeps controlled French politics, he personally groomed Georges Clemenceau for the French prime-ministership much as the Rothschild family groomed Macron in our time, so encouraging pro-French policies was encouraging pro-Szeps policies. Prior to his fall from grace, Szeps became what we recognize now as a “media mogul”, complete with his home “Palais Szeps” on Vienna’s tony Ringstrasse.

“Palais Szeps” in Vienna is now the Swedish Embassy.

Telegraphy was vital to Szeps’ informant network, as it was for the other Ringstrasse media moguls. Here’s UCLA PhD candidate Lindsay Alissa King’s take on the subject (2020):

The press industry expanded, relying on telegraphy for news transmission, introducing advertising to newspapers, and cheapening paper price per issue to increase circulation. ... In the decade after the uprising of 1848, a new generation of journalists in Vienna had transformed the archetypal image of the journalist from the literary man to the business-man, the forerunner of today’s media mogul. [Modes of Masculinity: Entertainment, Politics, and the Jewish Men of Vienna’s Press, 1837-1859]

Historians of the United States’s Civil War should look carefully at those dates. If traffickers in Lemburg, Vienna or Budapest could figure this racket out, could gangsters in Illinois not do the same?

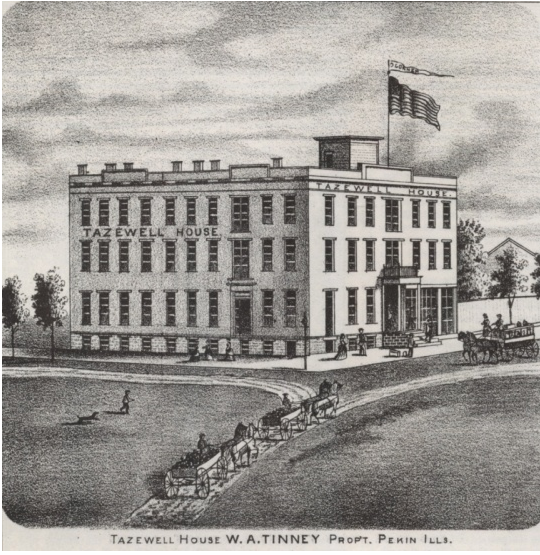

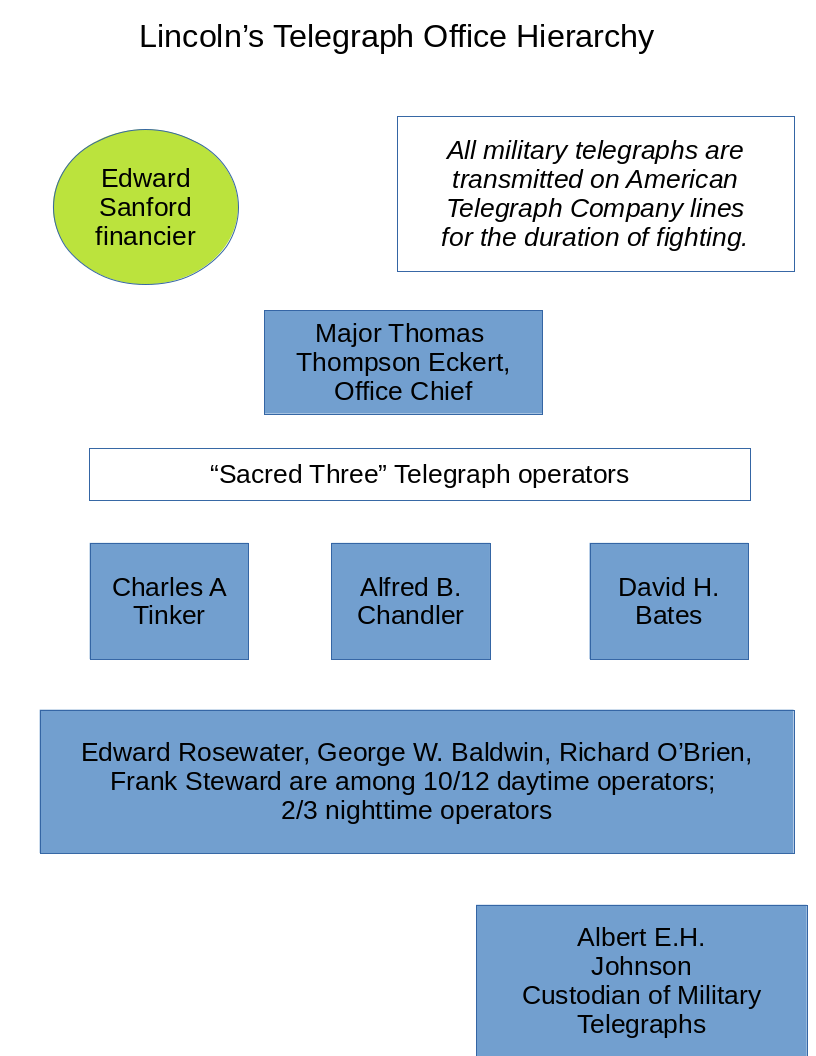

When Lincoln launched his war effort, there was no military telegraph office. Instead, the War Department was given a special connection by the American Telegraph Company, personally financed by its president Edward S. Sanford. The military’s first telegraph operator was Charles A. Tinker, an acquaintance of Lincoln who operated the desk out of ‘Tazewell House’ Hotel in Pekin, Illinois.

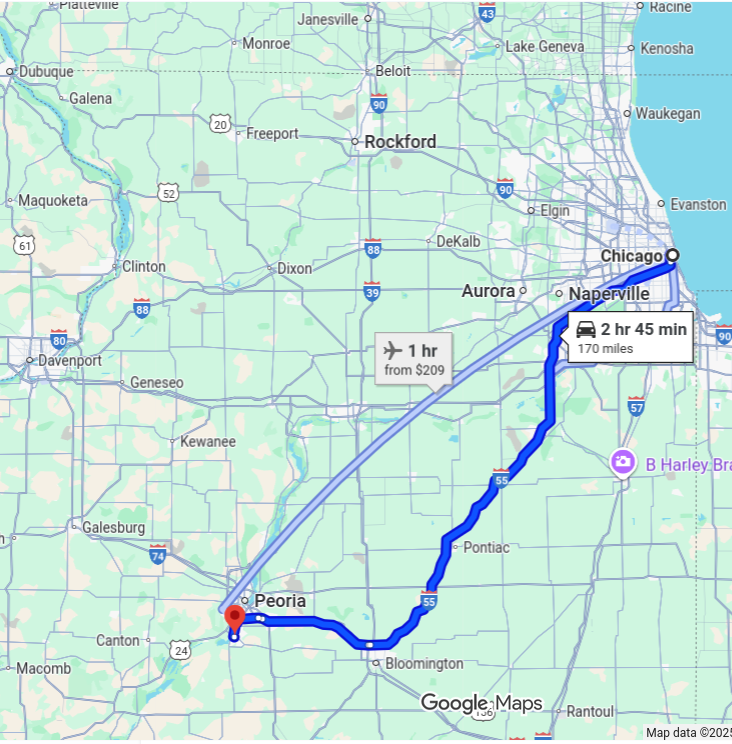

Pekin, IL lies just south of Peoria in the “Land of Lincoln”

“Pekin was first visited by Abraham Lincoln in 1832 immediately after the Black Hawk War, in which Lincoln served as a militia captain, private, and spy. While canoeing alone from northern Illinois back to New Salem, Lincoln's canoe broke at Pekin. Lincoln made himself a new canoe and proceeded on his way.

Later in the 1850s, as an attorney Lincoln visited Pekin. When court was in session Lincoln often stayed at the Tazewell House hotel at the corner of Court and Front streets. Later named Bemis House, the hotel was torn down in 1904. After Tazewell House/Bemis House was demolished, its threshold was preserved at the Tazewell County Courthouse, and was inscribed with words commemorating the fact that “Hereon trod the great Abraham Lincoln — Stephen A. Douglas — John A. Logan — Robert G. Ingersoll — David Davis — Edward D. Baker and others.””Thank you, Pekin Public Library.

Immediately there were problems with the telegraph office. Both President Lincoln himself and operators of Sanford’s military investment were leaking sensitive information to the press. Some leaks were used in newspaper-based financial market manipulations, just like in Vienna. Lincoln was such a bad leaker that Commanding General George B. McClellan told subordinates not to give telegraph messages directly to the president, nor the secretary of war. (McClellan was a West Point graduate; an actual veteran; and not from one of Lincoln’s “abolitionist” families.) Sanford’s men disobeyed these orders by “carelessly” leaving messages where Lincoln could find them. McClellan was fully aware of Lincoln’s unreliability, but not necessarily of that of Sanford’s American Telegraph men:

From McClellan’s “Own Story” we learn that he had no confidence in Lincoln’s military ability or discretion, and that he believed information communicated to him would be divulged to congressmen and others, and he therefore thought it best to give him [Lincoln] as little news as possible. [Lincoln in the Telegraph Office, Bates, p 45. 1907/2014]

This situation persisted for months and the new War Secretary Edwin Stanton called for an investigation into the leaks. McClellan’s captain and aide-de-camp in charge of the military telegraph, Thomas Thompson Eckert, was implicated. Stanton told Sanford, the angel investor, to sort out the situation with his American Telegraph men in Washington D.C.. Instead, Sanford ran to Eckert and told Eckert that his superiors were on to him.

You see, Sanford had saved Eckert from espionage charges in the South about a year prior. Eckert had been working for the Vice President of the Confederacy Alexander H Stephens as a gunpowder-making consultant. However the Confederate men Eckert worked with every day at the Steele gold mine in North Carolina were confident Eckert was a Northern spy. Vice President Stephens’ protection and Sanford’s railway and telegraph contacts spirited Eckert out of danger and into a commanding position with Lincoln’s new telegraph office in Washington D.C..

It wasn’t unusual for Lincoln’s telegraph men to be turncoats from the South. Edward Rosewater, later to become the Galician Gang crime boss of Omaha, Nebraska, was a telegraph operator who had worked for Jefferson Davis. (The head of the Confederacy.) Rosewater only started working with Lincoln once the Union had taken Nashville, where Rosewater lived. Rosewater claimed later in life that he was always a double-agent Northern spy— he was certainly good at profiting from chaos. What we can be sure of is that both Rosewater and Eckert’s goose was cooked in the South before they went North.

“Emacipation Proclamation” celebrity and bordello profiteer Edward (Rosewasser) Rosewater.

When Sanford understood that his man in Washington, Eckert, had been outed by military professionals, he pulled out all the stops to save his investment. As a team, Lincoln, Sanford and Ohio Governor John Brough (who was involved with Sanford’s telegraph business), mobbed War Secretary Stanton’s office and pressured him not to dismiss Eckert from the army. Instead, Stanton bought Eckert a horse and carriage; gave him the title of “Major”; and detached Eckert from McClellan’s oversight. Eckert would now be the War Department’s “Chief of the Telegraph Office”. He would preside over those undisclosed leakers and be host to President Lincoln, whenever the august leader should wish to read his, or anyone else’s, telegraph correspondence.

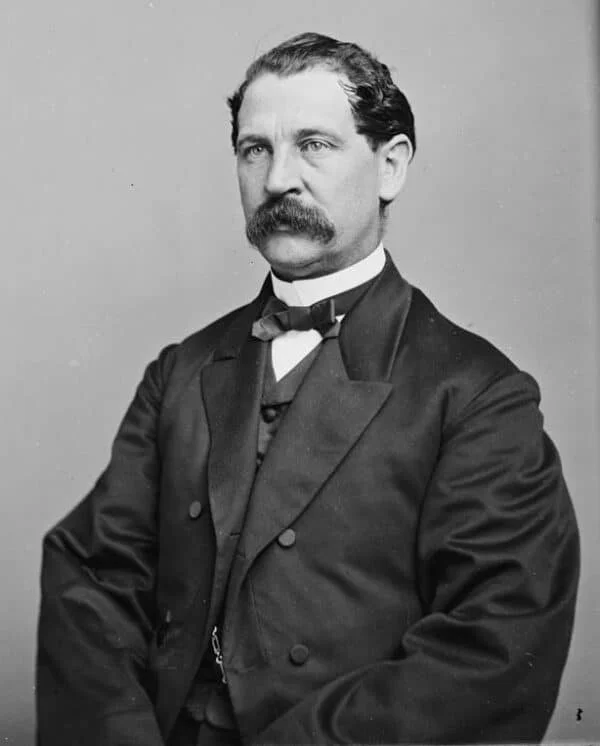

Major Thomas Thompson Eckert. Library of Congress

Should we be surprised that Lincoln would leak military secrets to the press? Lincoln was a product of the press. He was the bumpkin face chosen by Horace Greeley, the famous New York Tribune editor, to stand in for presidential candidate William Seward once Seward had made himself politically toxic. Greeley built Lincoln’s Midwestern career by organizing the purchase of The Chicago Tribune by Canadian Joseph Medill who dutifully followed Greeley’s orders to get Lincoln elected. Greeley was a shrewd political operator who understood how perception manipulation worked on both sides of the Atlantic.

Greeley kept Karl Marx on The New York Tribune staff as his European correspondent. Lincoln exchanged letters with Marx about the progress of his war and Marx used Hapsburg-supported Austrian newspapers to frame the US Civil War for his post-1848 European audience. Many Austrian/German 1848 revolutionaries were fighting in Lincoln’s war, and were even given high-profile commanding positions (like Heinrich Boernstein). These exiled ‘heroes’ were a sensitive topic for Austria-Hungary, because the top 1848 revolutionaries had made deals with Emperor Franz Joseph which sold out lower-tier organizers. Post-1848, the Hungarian and often the Jewish functionaries of the Emperor were largely ex-revolutionaries. Liberal newspaper owners (the big, respected newspapers) were almost always Jews who chose to give up revolutionary aims in exchange for cooperation with the Hapsburgs and the opportunity to make lots of money through stock manipulation. Many idealistic European radicals looked to Lincoln to continue the revolution they started. Marx was the man Franz Joseph entrusted with perceptions of Lincoln in his empire. Why?

I cannot stress enough how close Marx’s Vienna organ, Die Presse was to the Emperor and the cosmopolitan, ex-revolutionary liberal regime. Die Presse was bought by the government after 1848 and its editors became the doyen of Franz Joseph’s captured newspaper industry. It doesn’t get more government than Die Presse.

Heinrich “Henry” Boernstein was a vicious man who excelled in anti-Catholic propaganda as a US newspaper owner. An ex-1848er and a saloon operator, Boernstein was highly trusted by Lincoln and probably part of the Austrian Foreign Office’s spying apparatus. When he returned to Vienna he worked as a theater censor, which came under the jurisdiction of the police force and Foreign Office at that time.

According to Prussian Secret Service Head Wilhelm Stieber, his agents had disrupted Marx’s network by 1852 and had turned the socialists onto the Kaiser’s enemies. Maybe that is true. However, as early as 1842 Marx had taken up revolutionary activities in Paris with two Hapsburg subjects: the very Heinrich Boernstein pictured above, as well as Sigmund Freud’s in-law Karl Ludwig Bernays, who also wrote for Greeley’s New York Tribune. Obviously Greeley understood how the press worked in older, more sophisticated societies than that of New York or Illinois. Hapsburg and Prussian clandestine police aggressively employed penetration and subversion tactics.

Karl Ludwig Bernays. Sigmund Freud had married up. The Bernays were a higher-ranking family in Jewish Viennese society and even counted an Anglican Bishop among their ranks. Sigmund Freud came from a family of currency forgers.

So who were Lincoln’s whiz-kid telegraph “boys”? They were the men who formed AT&T’s “natural monopoly” of American telecommunications after the war. This monopoly lasted well into the 20th century. Through AT&T’s brokers Hayden, Stone & Co. we can trace the capital behind this AT&T monopoly into the heart of today’s “Silicon Valley”.

The men listed above would play an outsized role in the formation of AT&T’s national monopoly on electronic communication over the next decades. They were at every critical junction. Take, for instance, chief Eckert:

In the post-war decades, Eckert managed first the Vanderbilt family's Western Union and then its chief competitors, Jay Gould's Pacific Telegraph Company and the then American Union Telegraph. From 1893 to 1900 he was the president of Western Union, and then served as chairman of the company's board of directors until close to his death in October 1910. (University of California, Huntington Library Archives)

Chief Eckert aside, Charles A. Tinker, Alfred B. Chandler and David H. Bates all worked with Jay Gould to achieve Gould’s shocking takeover of Western Union in 1881. This gave Gould control of 80% of the US telegraph market. In 1885 Chandler went on to capture the remaining 20% as the driving force of Mackay’s Postal Telegraph Company. In 1907 the Lincoln Men at Western Union joined with the Lincoln Men at AT&T to dominate US and trans-Atlantic electronic communication until the outbreak of the Great War in Europe.

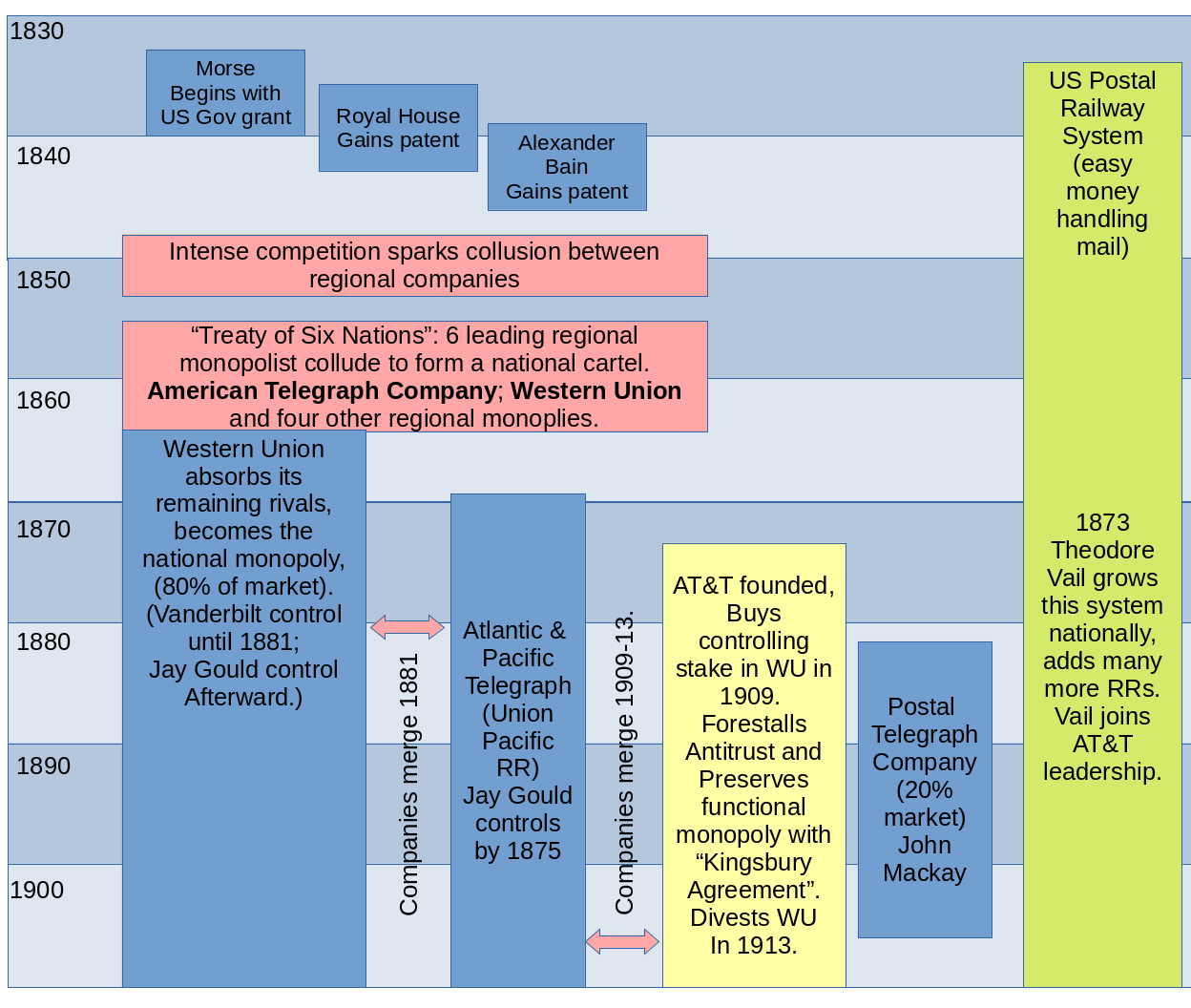

What does all that mean? Below is a time line showing how Morse’s telegraph company and its competitors became “Western Union” and how Western Union was absorbed into ‘Ma Bell’.

Timeline of the Western Union/Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph/AT&T merger.

Sam F. B. Morse started his company, “Magnetic Telegraph Company” with partners in 1845. One of these partners was Alfred Vail, the cousin of Theodore Vail who we’ll talk more about in a minute. Morse’s firm was given money by the state of Maine because the telegraph was intended to operate like a public utility. Instead, Morse’s firm was sucked into a morass of wholesome capitalism which drove down prices for consumers. Thomas Eckert got his telegraphy start working as an operator for Morse in the 1850s, then moving to Chicago.

While the telegraphers were struggling for profit, the railroads had found another way to grift the federal government: the US Postal Railway System. Beginning during Lincoln’s presidency, the Chicago Post Office partnered with 1) Chicago and North Western Railway and 2) the Boston-owned Chicago, Burlington and Quincy; and 3) Lincoln’s former employer the Chicago and Rock Island RR; and 4) the Pennsylvania and the Erie RRs to deliver mail. For this task railroads were compensated lavishly, making in excess of 106% of their expenses and taxes. Risk-free. That’s similar to a 6% return at a time when 2% was considered a good return on a moderate-risk investment, such as property development in northern Manhattan. Unscrupulous railroad developers (like James J. Hill) would categorize expansion-spending as a “cost of doing business” and have the Post Office underwrite their growth. Smart telegraph investors saw synergies.

The telegraph and the railroad were natural partners in commerce. The telegraph needed the right of way that the railroads provided and the railroads needed the telegraph to coordinate the arrival and departure of trains. These synergies were not immediately recognized. Only in 1851 did railways start to use telegraphy. Prior to that, telegraph wires strung along the tracks were seen as a nuisance, occasionally sagging and causing accidents and even fatalities. Economic History Association

Eventually the telegraph companies realized that if they colluded they could drive out competition and extract monopolistic prices just like the railroads. Regional behemoths emerged that sucked up smaller players. Before the Civil War there were six regional monopolies; by the end of Lincoln’s presidency Western Union had devoured them all, including the Union Army’s telegraph partner, The American Telegraph Company. The robber baron Vanderbilt family controlled Western Union, and they also controlled the Union Stock Yards of Chicago and the main rail line bringing that beef to its market out East (Michigan Central and New York Central RR). The Vanderbilts were the employers of Eckert after Lincoln, from The Library of Congress:

Following his 1867 marriage to Sallie Raphael Kenney, [David H.] Bates began a twenty-five-year career with the Western Union Telegraph Company, rising to the position of vice president. As was the case during the Civil War, his service at Western Union was under the supervision of Thomas Eckert.

Profiting from Chaos

In 1869 Jay Gould realized that he could leverage his growing interest in the Union Pacific RR to support a rival to the Western Union monopoly. He negotiated patent agreements with Thomas Edison for a controlling stake in the “Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Company”, the cables of which ran along UP tracks. With control of the A&P he initiated a rate war which forced WU to buy A&P with WU stock to stop the bleed. In exchange for peace, Gould won a controlling share of WU. Edison helped birth the monster that consumed the Vanderbilt Western Union monopoly by 1875. Imagine the enemies Edison made with that move. What role did the Lincoln boys play? From the University of California’s Huntington Library:

A key historical figure in the [Eckert] collection is Union Pacific railroad magnate Jay Gould, who employed Eckert in the 1870s to head his Atlantic and Pacific Telegraph Co. (and who, coincidentally, was a colleague of Collis Huntington, uncle of The Huntington’s founder, Henry Edwards Huntington). Gould’s bitter rival, William Henry Vanderbilt, controlled Western Union, and the archive sheds light on the telegraph wars between the two. Gould ultimately gained a controlling interest in Western Union in 1881; Eckert worked for both men at different times and served as president of Western Union from 1893 to 1900.

Jay Gould. A financial backer of Tammany Hall Boss “Tweed” and of President Ulysses Grant, Gould played both sides of NYC politics much as his contemporaries in Chicago, The Kentucky Colony, did.

Shades of the Civil War? Gould first appointed Alfred Chandler, a genuinely competent businessman, as general manager of Atlantic and Pacific and then president. Gould made David Bates ‘General Superintendent’— while Bates was still working under Eckert at Western Union! Tinker too was a Western Union employee at the time he joined Gould and Bates in the new “Union Telegraph Company” designed to serve Chicago…

New York Tribune, April 30, 1879. Page 1.

If you read that article above, you will see that less than two years prior to his takeover of Western Union, Gould incorporated a new company, “Union Telegraph Company”, with a chunk of change from Charles A. Tinker, David Bates, but not Albert Chandler. Gould then moved all of his “Lincoln Boy” talent save Chandler out of “Atlantic and Pacific” and into the “Union Telegraph Company”. Why? I can only speculate. To hide Lincoln-boy participation from the Vanderbilts? It seems unlikely that the Vanderbilts would be unaware that their telegraph employees were colluding with Gould. Perhaps this was a way of repaying Lincoln men for other favors. Gould had snatched their Union Pacific RR prize in 1873.

As soon as Gould’s merger with Western Union was complete in 1881, Tinker was moved to Brooklyn where he was general superintendent of the Western Union Telegraph Service. Bates enjoyed another 20 years at Western Union. Only Chandler was squeezed out: he became president of the less prestigious Fuller Electric Company, presumably with a bitter taste in his mouth. Chandler got his revenge hot.

Shortly after Gould won Western Union, there appeared a quartet of Irish stock manipulators lead by John Mackay, the silver king, who wanted into the telegraph market. Mackay partnered Alfred B. Chandler, and under Chandler’s expert management the “Postal Telegraph Company” scooped up that 20% of the American telegraph market that Western Union didn’t absorb. Postal was WU’s only real competitor, but while these two adversaries battled an even greater opponent was lurking on the airwaves.

By 1873 Alfred Vail’s cousin had come to the attention of Hayes’ Administration for his stellar postal-railway work between Lincoln-boy Edward Rosewater’s fiefdom in Nebraska and that of Brigham Young in Utah. Vail was whisked to D.C. where he would take his cushy postal-railway gig national and dole out even more cash to rail magnates. As you can imagine, he made a lot of friends and was widely liked. Enter the man who would win everything, Gardiner Hubbard.

Hubbard, who was also crossed by one-time business partner Thomas Edison, hired Theodore Vail to be a lobbyist/executive at this American Telephone Company. Vail played his pork-barrel contacts in D.C. to protect and grow Hubbard’s telephone concern until 1887. In 1887 ATC let Hubbard go because of creative differences balancing dividends to reinvestment.

Western Union was certainly pressured by the Mackay/Chandler camp but its greatest weakness was Gould himself:

Western Union could have easily gained control of AT&T in the 1890s, but management decided that higher dividends were more important than expansion. The telephone was used in the 1880s only for local calling, but with the development in the 1890s of “long lines,” the telephone offered increased competition to the telegraph.

By the early 1900s AT&T had another magic weapon: J. P. Morgan and London financing. British investors began a type of recolonization of the United States in the 1870s, often via Stateside supporters of Lincoln like the Chicagoans of the Kentucky Colony. In the 1890s fashionable NYC had stopped celebrating Evacuation Day and a “special relationship” was in the works for AT&T:

Competition had given AT&T a necessary push, forcing it to expand and grow, but it also weakened its finances. Between 1902 and 1906 debt grew from $60 million to $200 million. Through a series of bond purchases starting in 1903, financier J. P. Morgan tried to wrest control of the company from the Boston capitalists, beginning a free-for-all that lasted several years. When the dust cleared in 1907, Morgan and his New York and London backers had won, and they brought back Vail as president. Vail had left in 1887 because of differences with the Bostonians, whose view was focused narrowly on short-term profit. Vail and his backers had a wider vision than the Bostonians, believing they should create a comprehensive, nationwide communications system.

Or a “natural monopoly” as kind historians have termed it. These “New York and London backers” operated at the same time Kentucky Colony princess Bertha Palmer was grooming King Edward VII with sex shows thanks his confidant Ernest Cassel. In two years’ time Herbert Asquith would start his MI6 to harass British tariff reformers who threatened men like Cassel’s international business. Asquith would dubiously associate British tariffs with being “pro-German”, because German shipping interests stood to gain where men like Cassel would lose. These tensions are what actually lead to the British entering the disastrous WWI.

Under Vail’s shepherding AT&T went on to enjoy its functional telephone monopoly for most of the 20th century, despite “anti-trust” forces coming for other monopolies, like the Edison Trust. Vail, much like American Tobacco’s Benjamin B. Hampton, was able to engineer a political compromise with Roosevelt forces via “The Kingsbury Agreement”. This agreement required Vail to divest from Western Union, while allowing him to get independent phone providers hooked on AT&T hardware— i.e. extend the monopoly via technology patents rather than outright ownership. Patent-based monopolies were the order of the day, and it’s worth noting that Lincoln Telegraph custodian Albert E. H. Johnson died in Washington D.C. on May 14, 1909 as “one of the oldest practicing patent attorneys in the United States”. (The New York Times, Obituary Notes.)

Western Union— which I presume was controlled by the same investors before and after the 1913 divestiture— went on to reinvent itself as an electronic financial services provider. “Telex” and the “money-wire” are WU creations. It’ll talk about “Telex” in a future post, but suffice it to say that this early fax service was used as a business intelligence sharing tool from the 1960s to 80s. Having a “Telex” terminal was as service for the “pros”. The information this system carried was valuable and it would have been watched by “intelligence community” organs.

The title image is AT&T’s 1914 logo “The Spirit of Communication”.

UPDATE:

I know I’m getting old because I left out an important part of this Vienna/Washington D.C. story. Vienna’s Ringstrasse elite were thrown a curve-ball the same year as the Kingsbury Agreement: the forced suicide of their celebrity spy-hunter, Alfred Redl. Redl is a Yiddish surname. Redl committed suicide having been discovered as a double agent for Russia and his counterintelligence colleagues wanted to avoid a trial.

The scandal would have been hushed up, save a prominent Ringstrasse newspaper called Die Zeit had recently been purchased by Archduke Franz Ferdinand (the guy shot in Sarajevo) using money from the Rothschild family’s Creditanstalt Bank. The Archduke pushed hard and broke the Redl spy scandal story, which flung the Hapsburg’s multicultural integration program into sharp relief.

Die Zeit held a status something like our New York Times and had been built by Heinrich Kanner and Isidor Singer, whom I wrote about previously with regard to B’nai B’rith and the White Slave Trade. The Die Zeit money had come from a series of Ringstrasse art patrons whose taste was exactly like John Podesta’s. Key to Die Zeit’s success was its establishment of a dedicated Telegraph Office, decked to the nines in Vienna’s “Secessionist” style, which was favored by the Jewish community there.

A reconstruction of the entrance to Die Zeit’s fashionable telegraph outfit. All the furniture was bespoke to match the building, which housed a large corps of dedicated information traders.

Part of Redl’s celebrity status came from his association with the famous Fledermaus Caberet and the talent who preformed there. The Fledermaus was housed a few doors down from the Telegraph Office pictured above and was financed by Fritz Waerndorfer, the chief patron of Kanner and Singer’s Die Zeit before the Archduke bought it. The Fledermaus promoted the occult, pedophilia and fluid gender identity. Its star attraction, Marya Delvard, was similar to our Marina Abramović. The elite of Vienna’s prostitutes were sold on Fledermaus’s stage. Quite a fitting hangout for Austria’s traitor-in-chief, and an interesting comment on ‘Permanent Washington’.