Opera Spies!

“Soft Power” is a new term for an old concept. OxfordLanguages defines “soft power” as:

a persuasive approach to international relations, typically involving the use of economic or cultural influence.

For most of the eighteenth century opera served as a high-class way of expressing “soft power.” Political legitimacy was bolstered by the authenticity and caliber of the opera troupes which a government supported. This was true under absolutist governments, it was also true under the British-inspired constitutional monarchies which sprang up in Europe and South America. As democracy spread and oligarchs challenged aristocrat-run governments for power, oligarchs borrowed opera as a tool to legitimize their political and material gains.

The same held true for the United States of America’s New England region, where monarchism had long-standing roots. The champions of monarchism in the North were crime lords like the Livingston, Astor, van Rensselaer families— those families which might be called the “the Four Hundred”. The Livingstons only joined in the 1776 revolution against George III when they thought they had a chance of being kings of New Jersey. The highest percentages of pro-British public sentiment were in these New England states, where tenant farmers were given the same legal rights as European peasants, sometimes even less than those.

Now the term “the Four Hundred” comes from a New York Tribune article which Ward McAllister wrote in 1888. That a list of clubbable families had to be published in a newspaper suggests that these New Englanders were a victim of their post-Civil War success and that the institution was already on the rocks. The ultimate eclipse of this Anglo-Dutch group, who were also termed “Knickerbockers”, came with the implosion of the Knickerbocker Trust Company at the hands of J. P. Morgan following the Knickerbockers’ patronage of the Heinze brothers and their copper speculation countering the Rothschild corner. The Knickerbockers had supported the Edison Trust, too.

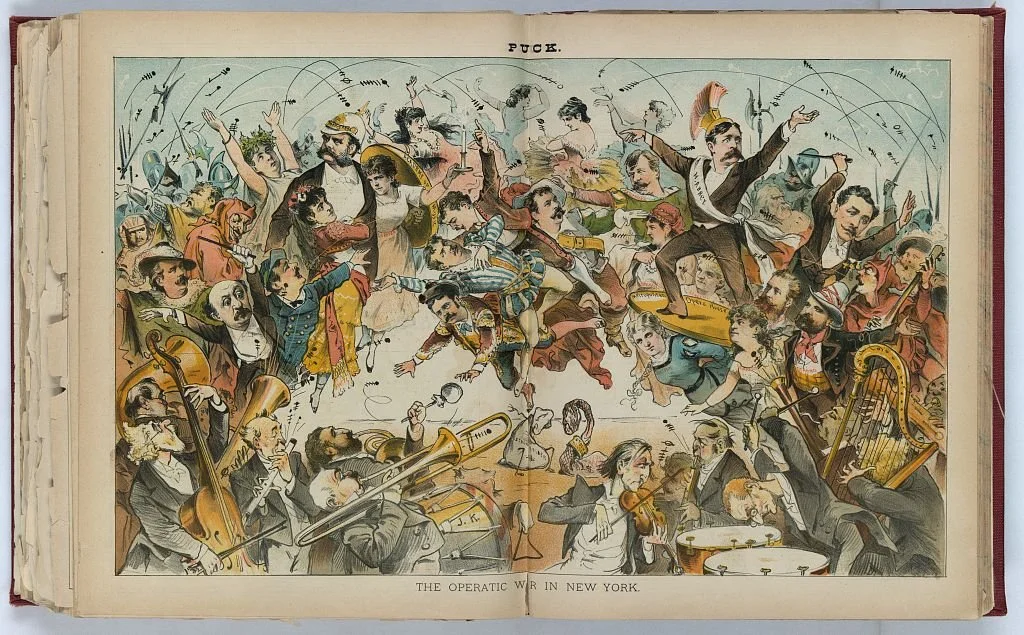

The “Robber Barons” were the foil to the Knickerbocker monarchists. They were the rich newcomers who wanted “in” yet had nothing but money to recommend themselves. These people are exemplified by the Vanderbilts, J. P. Morgan and the Roosevelt Family. (The people who befriended Empress Sisi of Austria.) These nouveau riche had made their fortunes in the wake of the Civil War and were now ready to throw their weight around with the monarchists. Naturally, the battle for social supremacy was conducted on the American operatic stage. Here’s Puck magazine’s 1883 lampoon of the situation:

“The Operatic War in New York” by Joseph Keppler. Puck, v. 14, no. 347, (1883 October 31), centerfold. Library of Congress

“Print shows a clash between the Academy of Music and the Metropolitan Opera, with Henry E. Abbey, opera singers, conductors, and orchestras; some of the identified figures include Marcella Sembrich, Sofia Scalchi, Galassi, Trebelli, Roberto Stagno, Mirabelli, Campanini, and Col. Mapleson.”

The image above shows the Academy of Music (Knickerbocker supported) versus The Metropolitan Opera (interloper supported).

The Academy of Music as represented by James Henry Mapleson, an English opera “impresario” (producer) who was patronized by the Knickerbockers. Mapleson was influential in London’s opera scene in the 1860s, but left for the NYC backwater and from 1879-1883 produced lavish displays. American musical battles were often a London vs Berlin vs Vienna affair. Prior to the Revolutionary War these battles were fought via book publishing with an eye towards influencing American Protestants.

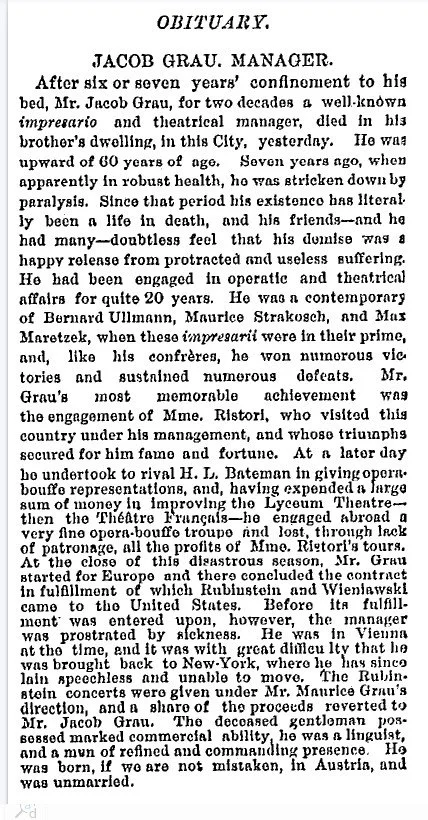

Henry Eugene Abbey was The Metropolitan Opera’s “impresario”. Abbey had a low-brow theater background and was a jeweler’s son from Akron, OH. Abbey’s only opera connection came from his Austro-Hungarian born partner Maurice Grau. Grau came from a family of Austrian theatrical talent agents, a dicey line of work connected to prostitution and human trafficking. Maurice seemed to rely on his uncle’s connections for sourcing musical talent.

New York Times, Dec 15, 1877.

Naturally, the Robber Baron’s money won out, however the new Metropolitan Opera House looked like an industrial building— it got the nickname “The Yellow Brick Brewery”— and the acoustics were poor. It also had over a hundred more box seats to sell than the academy building, which was drowning in a neighborhood of immigrant housing and socialist clubs. The old culture fell victim to the Knickerbockers’ and Robber Barons’ mutual addiction to cheap, disenfranchised labor.

The “Yellow Brick Brewery” aka The Old Metropolitan Opera House, courtesy Lincoln’s Carpetbaggers.

Genuine opera aficionados, much like the American Public, ended up the worse for this “elite” infighting.

Now a word on the Hapsburgs. Much— if not most— of that cheap labor on which the Knickerbockers and Robber Barons depended came from Austro-Hungarian lands. These workers included Italians and Jews who came to the USA with decades of Hapsburg political baggage. The Jews who immigrated in the wake of the Civil War came at a time when their people enjoyed unprecedented privilege in the Austrian Empire. At that time, pro-integration Ringstrasse Jewish art patrons were promoting a classicist view of their culture that celebrated assimilation into German society.

Post-1890 immigrants, Jews and Italians alike, had a different experience. Influential Jews from the “Ringstrasse” had only just regained power in Austria after political reversals following the 1873 economic mismanagement (from which they largely benefited). Following this exposure, a coalition of aristocrats, Czechs and Christians— a coalition far more representative of the peoples of the Austria Empires— had voted in a Ringstrasse-critical parliament which wasn’t broken until 1890 using franchise-expansion. In reaction to this 1873 correction and to military losses to Prussia, the Hapsburgs adopted an anti-German domestic policy which left German-speaking Jewish functionaries in rebellious provinces out in the cold… until they could make themselves useful again.

This temporary reversal terrified Ringstrasse power-brokers like the Szeps family who by the 1890s were advocating Jewish emigration out of Vienna to places like London and New York City. The Szeps were also pro-French (like Archduke Franz Ferdinand circa 1906) at a time their Ringstrasse coreligionists were pro-Prussia. The 1890s also saw the Ringstrasse patrons abandon democracy and “reform” politics in favor of aristocratic and occult philosophies. (They saw themselves as the embattled new aristocracy!)

After 1873, the Hapsburg-protected Ringstrasse barons disliked jury trials, because juries give popular opinion its place in justice. Compare this to modern Great Britain’s abandonment of jury trials.

Would you like to know more about these Judeo-Anglo-German “new aristocrats”? Check out my post on Otto Kahn and the Origins of the Intelligence Community. They are the pattern on which Jeffery Epstein and Les Wexner molded the “MEGA Group” of Israeli lobbyists.

1890s Italian immigrants were not in a pro-Hapsburg frame of mind, either. Modern-minded Italian nationalists held a grudge against the Hapsburgs for “occupying” “Italian” lands. By the 1890s disaffected Ringstrasse partisans in the Austrian Foreign Ministry were of a mind to partner with Italian separatists against the Hapsburgs. (To the dismay of military leaders like Field Marshal Conrad von Hötzendorf.) Ringstrasse partisans held the keys to the Hapsburg’s opera “Soft Power” weapons in Italy.

These weapons were formidable. La Scala is probably Italy’s most famous opera institution, but it was always a Hapsburg institution. The Hapsburgs used opera above all to legitimize their claims in the lands we (only recently) recognize as “Italy”.

Exterior of the “La Scala” opera house in Milan, Italy.

Prior to the 1848 revolutions, when oligarchical forces pushed for expansion of democracy, there was little Italian Opera without Hapsburg patronage and Italians were largely content with that situation. From "Verdi’s Emperor Charles V: Risorgimento Politics, Habsburg History, and Austrian-Italian Operatic Culture" by Larry Wolff [Austrian History Yearbook (2023), 54, 69–88. Cambridge University Press] :

The Italian figures who contributed to Habsburg culture were not just visitors; many of them lived and died in Vienna. In the case of Salieri, composing an opera for the opening of La Scala in 1778, it would have been difficult to say whether he was an Italian composer working for a special occasion in Habsburg Milan or whether he was a Viennese composer visiting Italian Lombardy under Habsburg auspices. These ambiguities of identity and context continued to be true in the early nineteenth century when Rossini, and then Verdi, wrote operas for performance in Habsburg Milan, Venice, and Florence, operas that were also performed in Vienna. In 1822, Rossini was still able to meet with Salieri in Vienna, seeking an introduction to Beethoven.37

Remember this guy? I joke, that’s actor F. Murray Abraham.

Yet, after the Ringstrasse clawed its way back to power in the 1890s, La Scala became a subversive institution. The nexus of this high-class culture-based subversion was a controlling clique of Ringstrasse patrons running the Foreign Office, Austria-Hungary’s preeminent espionage institution. (Read about all that and Alfred Redl.) The following excerpt is from the same paper quoted above, but I’ve highlighted the Ringstrasse-funded artists:

… Habsburg culture remained reciprocally concerned with Italy, even after the Risorgimento period, and notably in the modernist moment of fin-de-siècle Vienna. After Verdi’s final opera Falstaff had its premiere at La Scala in February 1893, in the composer’s eightieth year, the Milan cast went on tour and gave two performances in Vienna in May. Vienna, however, did not have a Falstaff production of its own until 1904, three years after Verdi’s death, when Gustav Mahler, as musical director of the Habsburg court opera, conducted the work (in German) with sets by Sezession artist Alfred Roller. In 1875, Verdi himself had come to Vienna and conducted Aida at the Hofoper [“High/Imperial Opera], but Mahler also conducted Aida repeatedly in Vienna between 1898 and 1903 (when he offered a spectacular new production), though it seems that he never conducted Don Carlos.80

Verdi’s popularity in Vienna was such that he continued to be performed there even during World War I—after Italy declared war against Austria-Hungary in the hope of obtaining, according to the logic of the Risorgimento, the Habsburg territories of Trieste, South Tyrol, Istria, and Dalmatia, with their partially Italian populations. Franz Joseph characterized the Italian declaration of war in 1915 as “a betrayal (Treubruch) the like of which is unknown in history,” and invoked “the spirit of Radetzky” on behalf of the Habsburg armies.81 Yet, the Hofoper still presented the most popular Verdi masterpieces between 1916 and 1918: Aida, Il Trovatore, La Traviata, Otello, Rigoletto, and Un Ballo in Maschera.82

In the United States, “Austrian” soft power was focused on shepherding the allegiance of influential immigrant organized crime networks— a 150 year old tactic at the time. Maria Theresa and her cronies like the Marquis de Pombal understood such networks and had used them to build Trieste. However by the 1890s this tactic was spinning out of Hapsburg control, with shadlanut Jewish families using state resources for their own ends at the expense of the empire. With NYC awash in Jewish and Italian immigrants from the Hapsburg lands, Italian opera was the natural go-to tool for Vienna-based soft power operatives, be they “fifth column” operatives or otherwise.

Imperial Prussia was also interested in influencing the urban Jewish working class in America. Typically, Prussian active measures consisted of funding socialist causes. (Read about socialist-stage Mischa Appelbaum’s love affair with Wilhelm II.) In the decades prior to Appelbaum, German expatriates like Dr. Florence Ziegfeld used their influence in both Austria and Prussia to source musical acts from the Kaiser’s personal military band and the Hapsburg’s Strauss family musical ambassadors. (Read the gory details.) These German musicians would then serve as public displays of Lincoln Men’s prestige during the Reconstruction period— particularly around Boston in the 1870s. (Bear in mind that at this time in the Anglophone world German lands were looked on as liberal, forward-thinking and leaders in higher education. That perception would only change with propaganda following Britain’s loss of economic dominance.)

Ten years later, when the Reconstruction money had dried up, Dr. Ziegfeld found purpose as prostitution-queen Bertha Palmer’s musical lieutenant in Chicago. The traveling musical acts Ziegfeld specialized in were well known in Europe as covers for sex trafficking. Nevertheless, Dr. Ziegfeld’s society aspirations were a regular feature in Chicago’s newspaper press for the masses.

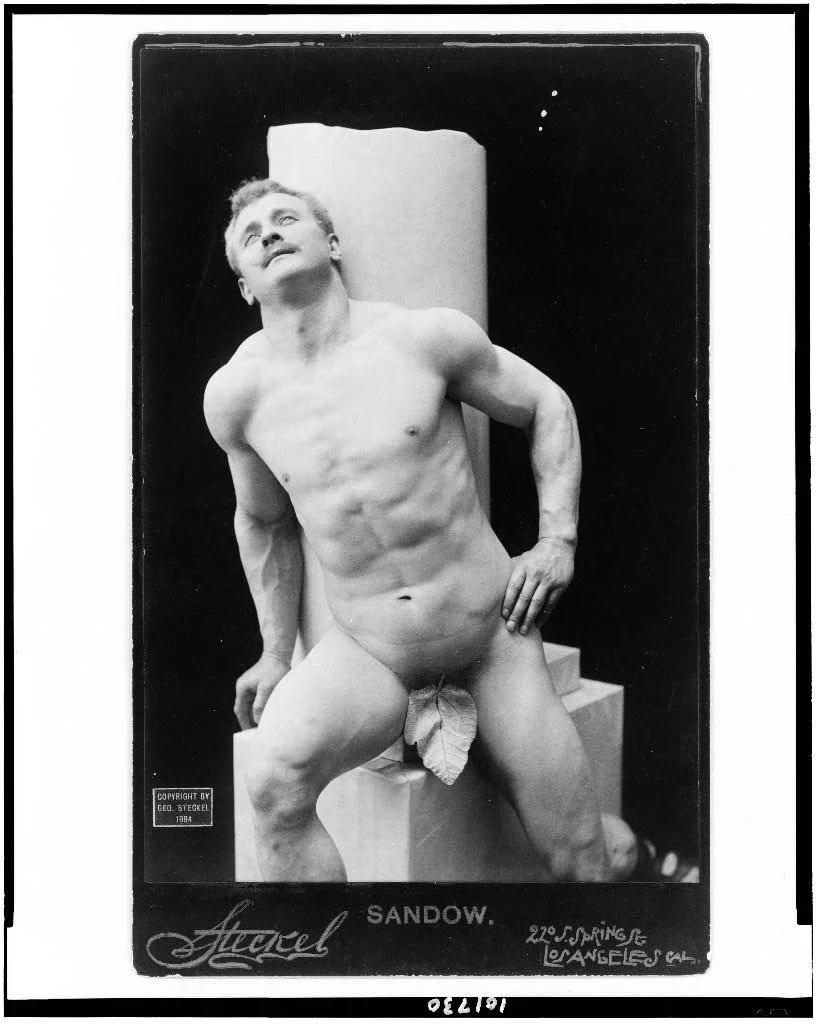

Flo Ziegfeld, Dr. Ziegfeld’s son, got his showbiz start displaying Eugene Sandow as part of the Kentucky Colony’s "Columbian Exposition” in 1893.

Ziegfeld wasn’t the only well-placed Prussian on the American musical scene. Oscar Hammerstein came from a well-off but abusive family in Szczecin, modern Poland but then part of the Prussian Empire. Oscar ran away to Liverpool which, alongside Manchester, had a large German Jewish settlement in the 1860s. (See my post on Counterfeiting and the Slave Trade for post-1776 criminal networks.) From Liverpool, Hammerstein found employment in New York City’s tobacco trade and was soon running his own cigar factory. It was the money from smoking that allegedly funded Hammerstein’s operatic forays.

“For the nearly forty years between 1871 and 1910, Hammerstein suffered, as the press put it, from the bite of the opera fly: all he wanted was to produce opera.” Italian Opera for the Yiddish-Speaking Masses, Herb Alpert School of Music.

In 1871 Hammerstein began financing opera at the Stadt Theater, which I believe to be the “New-Yorker Stadt-Theater Opera Company”. 1871 was also the year revolutionary Count Gyula Andrássy took over the Hapsburg Foreign Ministry, which had control of foreign espionage, “soft power” and “active measures” operations for the ancient empire. In 1851 Andrássy had been condemned and burned in effigy by the Austrian government for his role in the 1848 revolutions, but by 1871 he was the man censoring entertainment for foreign and domestic consumption.

Hammerstein’s earliest opera has all the earmarks of one of Andrássy’s “soft power” operations. “Stadt” is German for “city”, and the repertoire was entirely devoted to German works of a liberal stripe— perfect post-1848 reform-minded “Ringstrasse” material. It was located downtown in numbers 45-47 Bowery Street.

This German phase in Hammerstein’s career— a good 18 years— is usually glossed over by biographers. Following the 1848 revolutions in German Europe, domestic police and the Foreign Ministry cooperated to micro-manage everything about press and theater for propaganda purposes. Herman Boernstein, Lincoln’s German right-hand during the Civil War, was employed by this censorship apparatus when he returned home to Vienna. Andrássy, and other liberal Foreign Office heads, understood very well the power of subversion in the cultural sphere.

Read more about German Europe’s “active measures” targeting German immigrants in the North American Colonies: “German Spies in English Bookshops”.

The Germania Bank Building at 135 Bowery, now demolished, gives a feeling of German New York City. The North of the Upper East Side also had a sizeable German community. Persecution during WWII made expressing German culture dangerous.

In 1889 Hammerstein left the Bowery to team up with Daniel Frohman to create an English-language opera house in Harlem using Austro-Hungarian talent. This pairing obliquely coincides with the Hapsburg’s policy of discarding German identity in favor of “Austropean” multiculturalism, the cornerstone to Andrássy’s career. It more perfectly coincides with the Ringstrasse’s new Anglophone focus after regaining power from the aristocrat/Christian/Slav alliance.

The Harlem neighborhood of New York City is a topic dear to my heart as I lived there for a few years when I was young. Despite fitful attempts at gentrification, it’s now known as a no-go zone because of crime, largely caused by gangs of unsupervised black and Hispanic teens. (More Hispanic, less black.) In the 1870s Hammerstein was one of the large residential property developers who expanded Harlem. At that time the neighborhood included wealthy Jewish enclaves— a sort of Ringstrasse on the Hudson. You could still see the burnt-out shells of some of their mansions in the early 2000s. These Jewish neighborhoods were sold for black ghettos in an astonishingly quick period from around 1910, when black working class labor was pumped into the city and the Jews moved elsewhere. New York’s Jewish power broker Robert Moses is well known for his attitude toward his new Harlem neighbors— to all his neighbors, frankly.

Harlem World Magazine: “The Schinasi House is a 12,000-square-foot, 35-room marble mansion on Riverside Drive in the Upper West Side in Harlem, New York City. It was built in 1907 for Sephardic Jewish tobacco baron Morris Schinasi. The mansion was designed by Carnegie Hall architect William Tuthill and reportedly retains almost all of its historic detail, including a Prohibition-era trap door that once extended all the way to the river.”

Schinasi was one of the tobacco kings I wrote about in Cigarettes and the White Slave Trade. He made his cigarette fame at Bertha Palmer’s 1893 Columbian Exposition.

Hammerstein opened his Harlem Opera House in 1889, just a few blocks south of these richly carved mansions. He borrowed Daniel Frohman’s Lyceum Theater troupe to staff this endeavor— this too is rarely discussed by Hammerstein biographers. Under Frohman’s guidance an English-language Austro-Hungarian opera troupe took up residence at the house.

The Harlem Opera House, probably around 1900.

New York Times, September 15, 1889.

New York Times, October 28, 1889.

Emma (von) Juch was born in Vienna to an Austrian military family with naturalized US citizenship.

Why Daniel Frohman? Daniel Frohman was one of the big booking agents who controlled the theater world by monopolizing the supply of talent. This monopoly would be perfected in exactly seven years’ time as the “Theatrical Syndicate”. From another angle, Frohman dominated one of the Galician Gang’s key covers for sex trafficking. Galican Gang sex trafficking was a crime that was state-sponsored by the Hapsburgs. The life of these trafficked women and children was one of perpetual travel, as they were sold on an international market every few months for “fresh goods”. Hapsburg subjects could not travel freely and overseeing the travel-pass system was the captured Hapsburg Foreign Office.

Beyond Frohman’s excellent NYC theater connections, he was powerful in London’s theater world, where he could pull the likes of Crown Prince Edward and Lillie Langtry to promote his shows. In 1880, prior to Hammerstein’s soft power forays, Frohman had been hired by the British “Church Society” in NYC to combat Catholic proselytizing via his “Madison Square Theater” and Anglo-Jewish promoter David Belasco. The Church Society would have been cover for British government propaganda: activity we would expect from an “intelligence agency” these days, but would have come under the purvey of the British Foreign Office back then.

The Frohman clan had every reason to understand “soft power” operations. They were from Darmstadt, ground zero for German “soft power” operations since the time of the French Revolution and spymaster Johann Heinrich Merck’s “Volkaufklarung” publishing operation. Prior to their British engagement the family produced German operas throughout the Midwest— same target audience as Hapsburg agent Heinrich Boernstein. By 1900 the Frohmans were probably propagandists for hire serving the intelligence services/clandestine police forces which were developing throughout Europe. The roots of the Frohman’s theater power would have been the human trafficking networks run by Galician Gang pimps, the perennial behind-the-stage moneymaker.

Frohman wasn’t Hammerstein’s only helper in Harlem. The US Marines were on hand to fill his struggling playbill, too.

John Philip Sousa, Head of the US Marine Band 1880-92.

In a weird echo of Dr. Ziegfield’s Prussian follies, US Marine bandmaster John P. Sousa staffed Hammerstein’s opera for its 1898 season. Sousa called himself “Salesman of Americanism,” but I like to think of him as the “Sound of the Reconstruction”. Here’s the official Wikipedia take:

He [Sousa] led "The President's Own" band under five presidents from Rutherford B. Hayes to Benjamin Harrison. Sousa's band played at the inaugural balls of James A. Garfield in 1881 and Benjamin Harrison in 1889.[12][13]

Hayes was the one who pardoned Bone Latta. Harrison was a family relation of Chicago’s Kentucky Colony crime lords. Sousa was certainly selling Lincoln’s brand of “Americanism” to Jewish immigrant audiences in New York City in 1889, readers may cast their mind back to William Wesley Young’s 1913 pitch to the same crowd through his film “A Boy and the Law”, which he made with the creepy proto-“Boys’ Town” operator Judge Willis Brown.

Was the Harlem Opera House successful? I have seen nothing suggesting it rivaled the Met. Hammerstein went on to build many more theaters, but they were Vaudeville theaters, the type which became famous for Yiddish themes and blackface, and were a far cry from operatic undertakings:

His [Hammerstein’s] desire to present popularly-priced opera at his new, midtown theatre proved financially disastrous, forcing him into a partnership with Koster & Bial, variety show producers. Their union fractured in a flurry of name-calling, fistfights and court battles, leaving a bitter and vengeful Oscar…

Hammerstein’s post-Harlem investments. (Boy, that cigar factory worked hard!):

1890, The Columbus, vaudeville, Harlem.

1893, The Manhattan Operahouse, aka “Koster & Bial's Music Hall”, vaudeville, Midtown.

1895, The Olympia Theater, vaudeville, Times Square.

1899, The Victoria Theater, vaudeville, Times Square.

1900 The Republic Theater, vaudeville, Times Square. (Run by prize fighter David Belasco.)

1904 The Lew Fields Theater, vaudeville, Times Square.

The content and operators of these vaudeville theaters suggest that Frohman took complete control of Hammerstein’s operations some time in the 1890s because of Hammerstein’s financial mismanagement. Indeed Hammerstein was so disorganized with money it begs the question if he was just the face of the operation from day one:

For Oscar, money was a means to an end, not the end itself. Oscar cared very little for the comforts of success. He paid the highest salaries in the business, yet seemed oblivious to his own needs. His sons had to hide money in his top-hat so he wouldn't be stuck without trolley fare. He was equally indifferent to failure: "I am never discouraged. I don't believe in discouragement...To do anything in this world, a man must have full confidence in his own ability."

While Hammerstein’s low-brow property development was turning “Times Square” into a muddy vaudeville “nut house”, at the Metropolitan Opera the Robber Barons were a bit like the dog that caught the car. A German-Jewish financier by way of London named Otto Kahn saw his chance in 1905 when a Robber-Baron profligate son, James Hazen Hyde, ran into money trouble. Kahn was an intelligence asset for Emperor Franz Joseph.

In 1905, when he was 23 years old, Hyde was forced out of his birthright at the Equitable Life Insurance Company when he threw a lavish Versailles themed costume ball that cost US$200,000. Company financing appeared to be involved and the board kicked Hyde out. Kahn was right on the scene to profit from Hyde’s bad judgement: Kahn arranged for his in-law Thomas Fortune Ryan to buy Hyde’s shares in Equitable, and give the boy a much-needed cash injection. In return, Hyde used his influence to hand the Metropolitan Opera House over to Kahn’s directorial influence. Hyde then ran to France where he spent the rest of his life. Kahn proceeded to relocate the Vienna State Opera to Manhattan, later he would import La Scala and its director Giulio Gatti-Casazza. That’s how the Ringstrasse captured the Met.

James Hazen Hyde at the infamous 1905 Versailles party.

Here is where things get weird. In 1906, right after Kahn captured the Met, Oscar Hammerstein decided to have another go at the opera market. Hammerstein and Kahn competed for operatic talent: they were selling the same Ringstrasse-approved product. However, Hammerstein tried to sell Ringstrasse opera to lower class Manhattan Jews, while Kahn tried to sell NYC’s native elite on the same thing.

I’ve written a lot about Kahn’s opera already, he pushed Strauss’s Salome which was de rigueur among the Ringstrasse set but offensive to Christians. (Even J. P. Morgan fought Kahn on that one.) Kahn was very much in line with the Ringstrasse’s new-found affinity for aristocratic pretensions. Hammerstein’s packaging was entirely different, appealing to the “opera-inclined but anti-elitist bent of Lower East Side culture”. “Anti-elitist” is not a good choice of word, there was nothing anti-hierarchy about Hammerstein’s audience, but they saw their ethnic interests in contrast to those of NYC’s native elites. In fact, Hammerstein cashed in on the upper-class pretensions of immigrant Jews:

In his congratulatory letter to Boris Thomashefsky on the launching of his new Yiddish theatre newspaper Di yidishe bine (The Jewish Stage), Hammerstein noted that the Jews were “very important patrons of the Manhattan Opera House, and although they take mostly the uppermost seats, still their applause is more appropriate than that of those who listen below in the five-dollar seats,” observing also that “the success of a grand opera performance is very much dependent” on Jews. [4]…

The Yiddish press reported frequently on Hammerstein’s activities, portraying him as a bold, unflappable, persistent Jewish upstart who was fighting back against that exclusive, aristocratic bastion of wealth, the big bad Met. In addition to his democratic orientation, Hammerstein’s own Jewishness was clearly an important part of his appeal to Jews. The Yiddish press embraced him as one of their own, a Jewish immigrant who had made it into the big-time.

Hammerstein assumed his audience wouldn’t understand the opera they were being sold, so he created an “Education Program” instructing Yiddish speakers on how they should appreciate opera while flattering their taste:

Explicitly courting their patronage in both the educational and regular seasons, Hammerstein offered Yiddish speakers high-quality productions in an elite opera house while also making them feel welcome by finding ways to cater to their social and cultural preferences. In large part through coethnicity, Hammerstein connected Yiddish-speaking immigrant Jews to the glamorous opera scene, integrating them into the elite opera sphere. Even if this approach was self-serving in trying to maximize his audiences, Hammerstein still made Jews feel like they belonged in his opera house, not merely marginalized outsiders grudgingly being admitted into elite precincts. Hammerstein thus brought the elite and popular realms together, eliminating the snobbishness of the elite opera and making it accessible while retaining its allure and prestige.

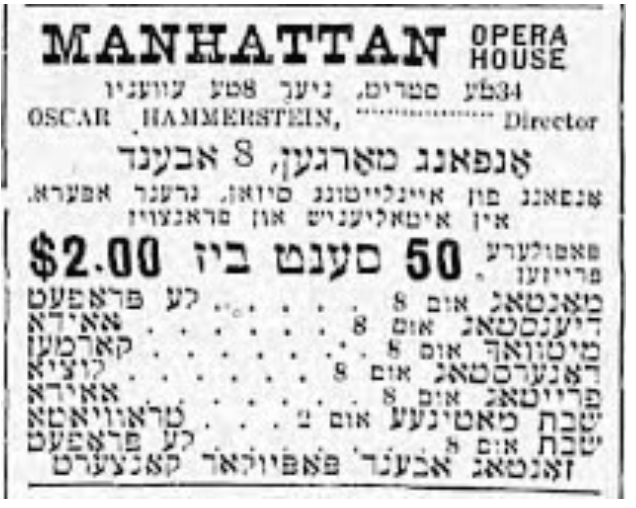

Italian Opera for the Yiddish Speaking Masses: “Ad for the Educational (here translated as eynleytung) Season, Jewish Morning Journal, August 29, 1909.”

Even with all this coaching, Hammerstein faced an uphill battle:

Hammerstein’s first season was not a financial success. He was at a great disadvantage in terms of repertoire because he was unable to develop a contingent of German performers. In addition, he was prohibited from presenting the operas of the most popular composer of the day, Giacomo Puccini, whose scores were the exclusive property of the Met.

Why? Why were working-class Jews being sold the same ideas as NYC’s native elites? Europe was gearing up for war. The battle lines were drawn between British and Prussian economic dominance and the USA had not yet chosen a side. The Ringstrasse straddled all sides. They knew from 1873 that they were vulnerable in the USA if they didn’t control voting blocks in key cities. They knew that they wanted to transfer their power base to the Anglophone world, but they still depended on Hapsburg state support. America could surrogate that support. The danger came from British-aligned interests that didn’t trust them. Kahn and Hammerstein represented manufactured diversity and an attempt at “elite capture”.

This strategy is in keeping with the way the Hapsburgs ran media after 1848. Their goal was to steer public debate with the appearance of competition and diversity. In practice, all newspapers were controlled by the state through ransomed cash funds; and access to postal systems; and a newsagents’ permitting system. In practice, all theater was approved by the censors prior to being staged. (What went wrong is that the Hapsburgs lost control of the censors.) At times, this manufactured diversity presented itself as a “Heglian Dialectic”, for example between a paper like the catholic Reichspost and the plethora of Jewish-owned liberal papers, lead by Neue Freie Presse. I put it to readers that a similar dialectic was at play between Hammerstein and Kahn during NYC’s second Great Opera War, 1906-1910.

The dialectic came none too soon. A fire had been lit under the Ringstrasse in 1906 when Archduke Franz Ferdinand bought the struggling Ringstrasse flagship, Die Zeit, using Creditanstalt money. The archduke moved the paper away from effete Oscar-Wilde inspired foppery to a more serious, peace-minded and pro-aristocracy voice in Viennese politics. This was contrary to much of the Ringstrasse’s interests, which looked to expand their state-supported markets into Ottoman lands and who were gunning for war with Serbia. The archduke, who was stronger than his uncle, was attempting to slip Vienna out of the Ringstrasse’s grasp. The colonization of the USA had to begin in earnest.

Both Kahn and Hammerstein ran franchises of the their opera programs. Hammerstein opened a Philadelphia branch in 1909, while Kahn set up the Chicago Grand Opera in 1910 and the Boston Opera Company in 1908. All of these branches closed by 1914, when Austrian resources were exhausted by WWI. Guess who helped Kahn set up the Boston branch?

Boston Evening Transcript, March 26 1908

There should be nothing surprising about Hayden, Stone & Co, the Lincoln Men’s brokerage, siding with a nest of Austrian intelligence agents to pervert domestic politics. After all, that’s what they did during the Civil War. But andreanolen.com readers know that by this time Hayden, Stone & Co. were cooperating with the Guggenheims, the Rothschild’s copper agents, and in short order Hayden, Stone & Co. men would be entangled with elite-capture pedophile rings in Nebraska.

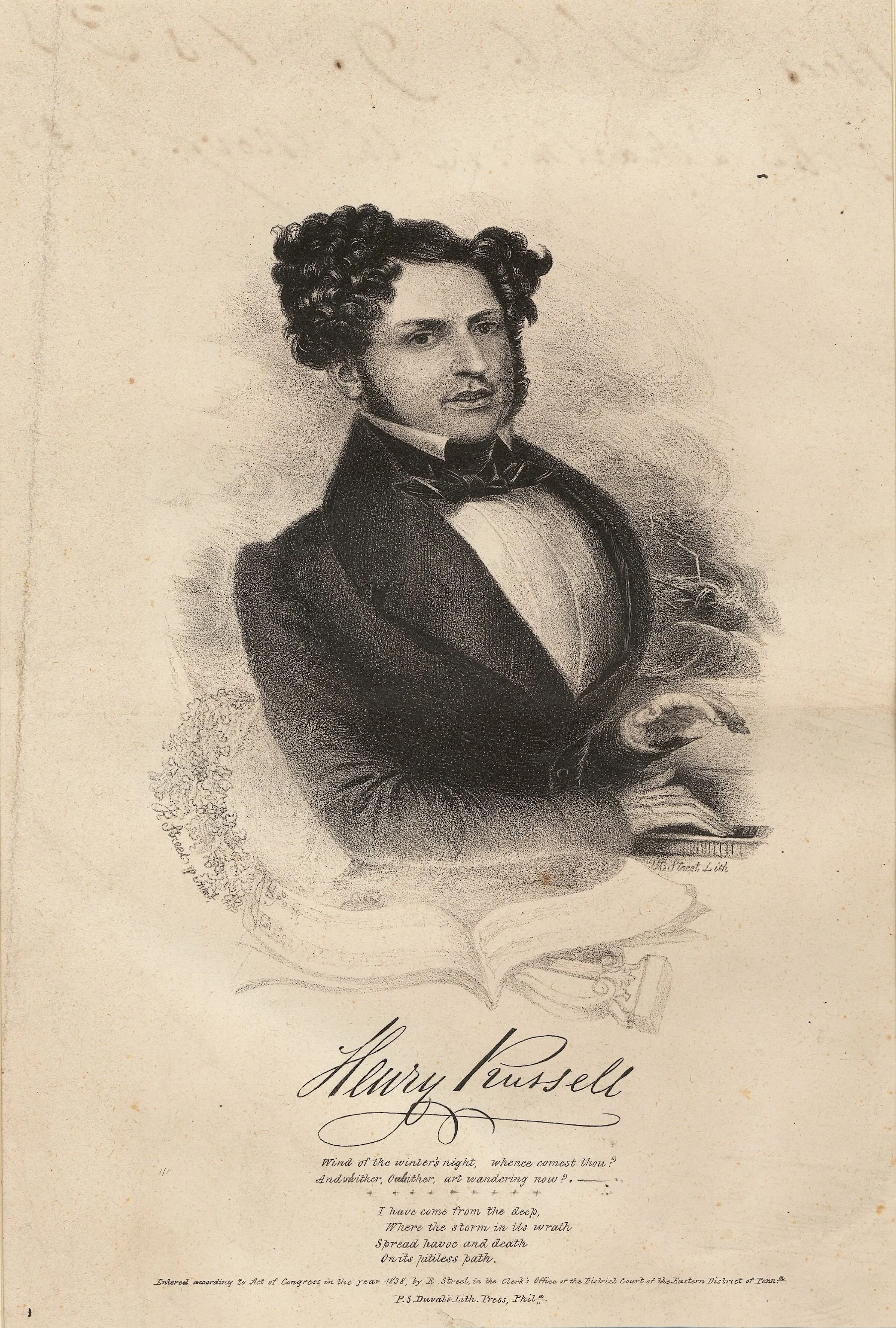

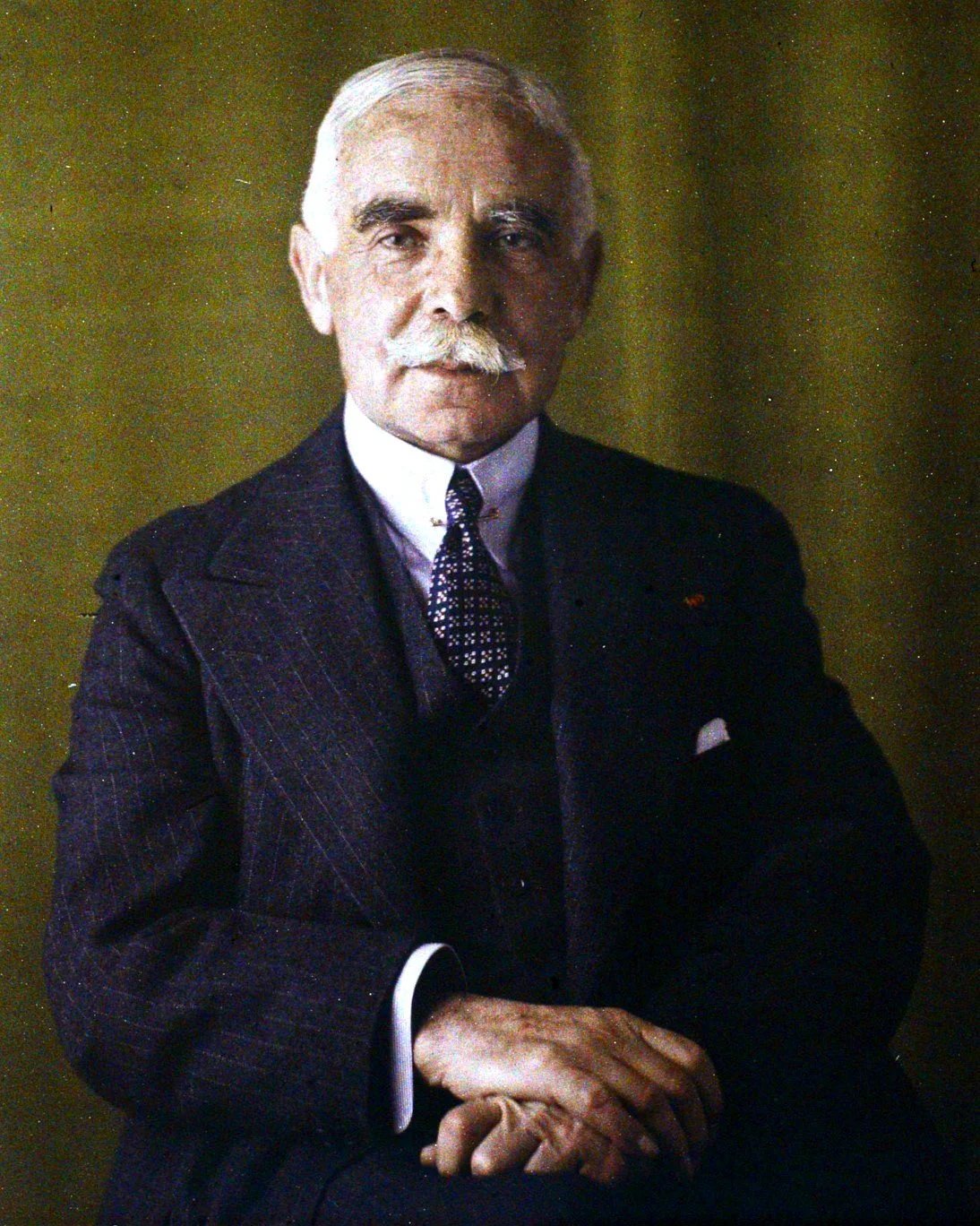

Hayden, Stone & Co.’s operatic foray deserves some scrutiny. Their “impresario” was Henry Russell. Russell was from a Jewish rabbinical family in London, whose ancestors included Chief Rabbi Solomon Hirschel. Russell’s father lost his shirt investing in the second incarnation of Alexander Hamilton’s “United States Bank” scheme, but then married into the notorious Lloyd banking family. Kahn’s Russell was trained by Hapsburg-sponsored opera musicians in Italy, where he married a descendant of the Marquis de Pombal, Maria Theresa’s soulless lackey and admirer of British “unorthodox investors”. From there Henry Russell set up his own opera in Naples; was invited to Covent Garden for a season; and then joined Otto Kahn in Boston. Russell was a comforting English face for Kahn’s Vienna-sourced money.

Boston’s impresario Henry Russell Jr.

Henry Russell Sr.

By 1910 Oscar Hammerstein and Otto Kahn came to an agreement where Kahn would take over Hammerstein’s operations. Of course, by 1914 all bets were off and opera was falling to the cultural sidelines. Modern jazzy stuff would be the next big battle.

Things did not go well for Otto Kahn as an intelligence agent. He tried. By the end of the war he was openly stumping for Franz Joseph from the ballet stages he patronized, but no one was buying it. In 1931 he lost all his patronage money when the Creditanstalt, the Vienna Rothschild’s bank, went bankrupt. He died a depressed man and pessimistic about global culture.

Why? Kahn was the originator of so many “American” institutions and historical sacred cows, such as the Harlem Renaissance, an early “black power” movement. I would add the legacy of the Hammerstein Broadway family to Kahn’s list. Why wouldn’t Otto Kahn be hopeful and ecstatic? Isn’t the change real?

Ironically, Kahn’s “active measures” lieutenants in Harlem, Carl van Vechten and George Sylvester Viereck, would end up being charged as Nazi spies and their hard work appropriated by the CIA’s “Congress for Cultural Freedom.”

I’m actually not laughing as I type this, because the weaponization of high culture in the United States lead to its death… and death along depressingly predictable lines. Readers may remember Peggy Guggenheim and her CIA-sponsored, paint-splattering boyfriend Jackson Pollock. Unfortunately, the same thing happened to opera.

And the spooks won’t even stand by their creations.