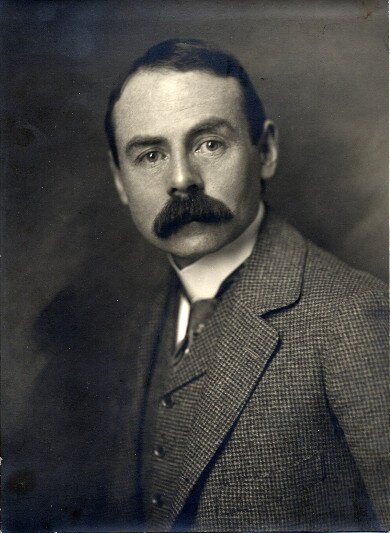

Otto Kahn as an Austrian Intelligence Agent

Otto Kahn, America’s early-film king-maker and high-profile partner of Kuhn, Loeb, & Co., was almost certainly an intelligence agent for the Austro-Hungarian Empire and continued to serve interests inside the Republic of Austria until his death in 1935.

This post will deal with the fascinating progression of Kahn’s activities which, taken as a whole, leave no reasonable doubt as to what line of business Otto Kahn was actually in. I’d like to remind Goetz historians of why Otto’s spy-work has such a close connection to Monroe, WI:

1) Otto Kahn was a principle investor in John R. Freuler’s Mutual Film Company, the firm that lead the charge against the Edison Trust and formed the military/president’s office/early film biz collaboration that resulted in Hollywood.

2) Otto Kahn supported William Wesley Young’s astroturfing work in NYC via the Humanitarian Cult, an operation which exploited the socialist voting block in Brooklyn and the other boroughs.

3) Otto Kahn supported the Ziegfeld Follies which orchestrated Edith May Leuenberger’s “National Salesgirls Beauty Contest” win.

4) Otto Kahn was a principle investor in Mutual Film subsidiary Arrow Film, which employed Leon Goetz’s Monroe employers, the Gruwell family.

The truth of Kahn’s espionage work was no secret to his financial competitors around the Morgan banking interests and at the Bank of England, however there has been an effort by academics and writers who are keen to salvage Kahn’s cultural legacy to white-wash his wartime pro-Austria media stunts and deny his firm’s WWI war loans to the Hapsburgs.

Otto Kahn’s espionage will be acutely embarrassing to any culture-vulture who draws self-worth from the following “American” art icons: The Metropolitan Opera, its director Giulio Gatti-Casazza, sometime conductor Gustav Mahler, and set designers Joseph Urban and Norman Bel Geddes; the Boston Opera Company; the Chicago Opera; the music of Black activist Paul Robeson and writers of the Harlem Renaissance; the “cosmopolitanism” of the Ziegfeld Follies; the promotion of Oscar Wilde’s work in the USA; the socialist politics of the Abbey Theater, the New Playwrights Theater, the Moscow Art Theater in the USA, the Civic Repertory Theater and Eva Le Gallienne, or that of the “New Theater”/Century Theater and dancer Isadora Duncan; the Provincetown Players and Eugene O’Neill; the “modernism” of dance troupes like the Ballet Russes in America and its satellites Anna Pavlova, Vaslav Nijinsky and George Balanchine; film collaborators Upton Sinclair and Sergei Eisenstein; the music of George Gershwin; documentary film maker Max Eastman to name a few. These sullied giants are, of course, beyond those early film luminaries already connected with Kahn on this website: D.W. Griffith; Paramount Pictures; Jesse Lasky; Charlie Chaplin; Mary Pickford; Lillian Gish; John R. Freuler; Mutual Film Company… all the greats of early cinema.

A sampling of some of the musical giants Kahn funded with Viennese money:

Otto Kahn’s flagship cultural undertaking was his financial sponsorship of the “Metropolitain Opera” in New York City.

“Robeson was one of the most important figures in an alliance between Maoist China and politically radical African Americans.” Courtesy Aeon.co and Gao Yunxiang, professor of history at Toronto Metropolitan University in Canada. Robeson’s political trajectory was established by Otto Kahn’s post-1918 patronage footprint. Gao continues: “Robeson’s adoption of the song ‘Chee Lai!’ into his repertoire led to a closer relationship with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the People’s Republic of China. In 1949, following their victory over the Nationalists, the victorious CCP made ‘Chee Lai!’ China’s national anthem.” For Otto Kahn’s financial interests in China, please see my post on Monroe’s Princess Theater.

It is not enough to say these American luminaries wittingly or unwittingly took Austro-Hungarian, later Austrian Republic, “soft power” espionage money. They served very specific interests inside this fractured empire and fractured country.

These luminaries were spokespersons for the cultural program espoused by Emperor Franz Joseph’s main espionage apparatus: the intelligence network shared between Austria-Hungary’s Foreign Office and the internal police, who together oversaw the empire’s public performance spaces and managed theatrical reviews in all newspapers. This apparatus survived the Hapsburgs. Kahn’s generous contributions to the American arts scene began on an industrial scale around 1907 and continued well beyond 1918. Kahn’s largess only stopped— and stopped abruptly— with the 1931 bankruptcy of the the Rothschilds’ bank in Vienna, the Creditanstalt.

The Creditanstalt’s headquaters on the Freyung triangle in downtown Vienna. An institution never far from corruption and scandal, the Creditanstalt building is now owned by financial goliath Unicredit.

There are many reasons why 1907 and the Creditanstalt are hugely interesting for this Austrian Foreign Office/Police culture-offensive, which I call the “Ringstrasse Offensive”. The most damning of these reasons involves Archduke Franz Ferdinand— the guy shot in Sarajevo— who invested heavily in this same cultural offensive around 1907 when he purchased the Viennese newspaper Die Zeit away from its cash-strapped Ringstrasse sponsor Fritz Waerndorfer. Die Zeit was the leading “avant gard” print mouthpiece and took a pro-Serb, pro-French, anti-war stance that was uncomfortable to the Ringstrasse Patrons after the archduke’s purchase. Franz Ferdinand probably used Creditanstalt money to make this investment. The Fledermaus Cabaret, another of Waerndorfer’s avant gard investments in Vienna, also appears to have enjoyed a massive cash injection at this time. (It closed weeks after the suicide/execution of military spy chief and Russian double-agent Alfred Redl.)

Above and beyond all this, however, the “Ringstrasse Offensive” was a post-1890 cultural program espoused by nouveau riche merchants and bankers with whom Emperor Franz Joseph partnered after the 1848 revolutions. These Ringstrasse Patrons, largely Jewish bankers and beneficiaries of state-sponsored monopolistic enterprises, controlled all leading newspapers in Austria-Hungary with Franz Joseph’s blessing. As often siding with revolutionary interests as with those interests which superficially appeared to be “conservative”, the Ringstrasse Patrons had particular synergy with the rebellious Empress Elisabeth and her unstable son Rudolf. “Conflicted” is the only word for this bizarre political situation.

[I wrote previously about the Ringstrasse with respect to their love of Renaissance Hermeticism in architecture and Freud’s concept of the “Zwischenreich” or psychic space for subliminal influence.]

The Ringstrasse Patrons are important to Otto Kahn’s story because they were particularly well represented among Alois Lexa von Aehrenthal’s ruling clique at the Foreign Office (e.g. “Jung Wien” writer Leopold von Andrian) by the time of Kahn’s New York City activities. This clique had complicated loyalties, often siding with Italian separatists at the expense of the Austro-Hungarian military (and ultimately) territorial integrity.

Leopold von Andrian, one of Foreign Minsiter Aehrenthal’s insiders and therefore privy to Austria-Hungary’s most sensitive intelligence networks, was also part of the Jung-Wien literary group sponsored by the Ringstrasse Patrons. Thank you, MakingQueerHistory.com.

At the center of this mercurial intelligence/art industry nexus was Vienna’s captured newspaper industry. The daughter of preeminent fin de siècle newspaperman Moriz Szeps (who had a mentor/disciple relationship the Crown Prince Rudolf) described the “Ringstrasse Offensive” in this way:

“For a decade now our city [Vienna] has united elements that, through a strong shared feeling, through a special active creative force, indeed, through a mutual aesthetic and ethical creed have been closely connected to each other. The art culture, on the crystallization of which they have been working, produced powerful seeds of progress [disseminated] far beyond our country.” [Bertha Szeps Zuckerkandl, “Kunst und Kultur: Das Kabarett 'Fledermaus'.” Wiener Allgemeine Zeitung, October 19, 1907.]

“My Living Room contains Austria”: Bertha Zuckerkandl and her Times. Herold’s book takes it title from Berta’s personal correspondence. The Szeps family were Galician Jewish transplants to Vienna when Berta’s father gained power. International sex trafficking was controlled by Galician pimps at this time. This photograph of Berta was taken 1908 or earlier.

A “Teagie” hostess ensemble from Lucy Duff Gordon, 1912 by “ Lucile”, item held by The Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Follow the link above for an explanation of what 1890s bordello chic meant to the early film industry “far beyond” Zuckerkandl’s country.

Mexican actress Lupe Velez in the 1920s promoting the 1890s bordello chic which Berta Szeps Zuckerkandl and her Ringstrasse ‘gesamtkunstwerke’ crew made famous decades prior.

In the quotation above, Szeps Zuckerkandl was describing the Cabaret Fledermaus as a manifestation of the ‘gesamtkunstwerk’— shared “Art and Culture” program— of the Ringstrasse Patrons, for whom she and her father spoke. A remarkably honest description of these patrons and their agenda can be found in Elena Shapira’s Style and Seduction: Jewish Patrons, Architecture, and Design in Fin de Siècle Vienna. The Rothschild family, and by extension their bank the Creditanstalt, were at the core of the small, interrelated set of families who made up the Ringstrasse Patrons.

Advertising image for the Cabaret Fledermaus as celebrated by Berta Szeps Zuckerkandl: a cabaret featuring heavily sexualized content for wealthy but artistically uneducated patrons.

How did these Ringstrasse Patrons get their fabulous wealth? The short answer is state-sponsored organized crime, the type of crime which I’ve written about a lot on this website and of which the White Slave Trade was a core component. Lending for wars, selling people as slaves or mercenaries helps too. A recurring theme in European history is that of Jewish shtadlanut leaders (‘court Jews’) stepping in to finance imperial wars which are unpopular among native aristocracies. For most of the 1800s and until their collapse, the Rothschild bank was the Hapsburg’s only lender, i.e. they had enormous financial power inside the ailing empire. In return, they and their in-laws were given control of mining, transportation, shipping, sugar manufacture and other monopolies. The results for the Austro-Hungarian economy were disastrous.

When the free-wheeling stock-jobbing of the 1860s and 70s came to a catastrophic halt, the Ringstrasse’s political party, the Constitutional Liberals, lost power to a new majority in the Abgeordnetenhaus (Congress) comprised of Aristocrats, Slavs and Catholic parties. This was a traumatic event for the Ringstrasse, who feared losing the emperor’s favor and power for good. Ringstrasse spokespersons like Berta Szeps Zukerkandl openly speculated in the press about the merits of relocating their base of operations out of Vienna and to the Anglo-American world. Through astroturfing burgeoning nationalist movements Ringstrasse representatives were able to wrest power back in the 1890s. With this power came a steady stream of cash to fund their aggressive, often anti-Christian, “avant gard” cultural activities.

George Minne’s sculpture “Kneeling Boy”, 1898. This figure was interpreted in a sexualized way by Ringstrasse Patrons and was a “calling-card” for their avant-gard “club” according to Elena Shapira, Pedophilia was widely normalized among these “gesamtkunstwerke” creators. The sexual grooming of children is a sine qua non of the international sex trade, which underpinned so much of the Austro-Hungarian economy, particularly in the Eastern European regions from which most Ringstrasse Patrons had recently emigrated prior to settling in Vienna.

There were certain artists and themes which were repeatedly promoted by this small group of moneyed Viennese patrons. For instance, they couldn’t get enough of Oscar Wilde, Henrik Ibsen or the composer Gustav Mahler. They championed internationalism, socialism, Austrian imperial expansion, and described themselves with dubious adjectives like “Austropean”. They greatly appreciated the biblical story of Salome and the mythical story of Narcissus. They worshiped the feminine/masculine archtypes of ‘celebrated prostitute/ erotic female dancer’ and the ‘dandy’. These same themes characterize Otto Kahn’s patronage of the Metropolitan Opera from 1907, which really was his flagship cultural undertaking.

Kahn got his “in” at the Met through James Hazen Hyde, heir to the Equitable Life Insurance fortune and NYC native. It was Hyde’s artistic education and finesse which opened the Met’s doors to Kahn. After being somewhat blackballed by his Anglophile peers, Hyde lived out his days in France, with Kuhn Loeb duplicitously ‘managing’ his business interests back home. In 1905 Hyde had sold his stake in Equitable Life under duress from Kahn’s mentor Edward Henry Harriman, the lucky buyer was our old Goetz friend, Thomas Fortune Ryan. Kuhn Loeb had also underwritten T. F. Ryan’s eye-wateringly corrupt 1902 street rail transit debacle “Metropolitan Securities Company”. Kahn’s daughter Margaret “Nin” would marry T. F. Ryan’s son John in 1928.

A 1905 Puck cartoon by Udo J. Keppler, lampooning financial bigwigs, including Thomas Fortune Ryan at the far left, wearing their insurance industry hats. Image held by the Library of Congress, courtesy of the Theodore Roosevelt Center:

“Thomas Fortune Ryan, J. Pierpont Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, and Edward Henry Harriman appear as sheikhs listening to a diminutive Grover Cleveland, labeled "Insurance Arbiter," standing at a desk, shaking a stick at them. Caption: What shall we do with our ex-president? - Anything but this.”

In truth, under Kahn’s patronage the Met would have been more rightly named the “Vienna State Opera based in New York City”. Kahn’s cash brought Giulio Gatti-Casazza in as director. Gatti-Casazza gained fame running La Scala in Milan, an opera house founded by Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, which had transformed into an Italian separatist bastion, a “symbol of the Risorgimento”, under Franz Joseph. Just the sort of Italians who found sympathy at the Foreign Office. Short on Giulio’s heels, Kahn brought over conductor Gustav Mahler thereby ending Mahler’s decade-stint leading the Vienna State Opera, the repertoire of which was censored by the above-mentioned Foreign Office/Domestic Police intelligence network. Mahler was a good friend of Berta Szeps Zuckerkandl, too.

Most people will probably have heard of opera singer Enrico Caruso who, along with Heinrich Conried, was was an early recipient of German-Jewish patronage in New York City. Kahn brought Caruso to the Met, but Caruso’s background is more nuanced than Mahler’s. Caruso is famous because prior to moving to NYC, he signed a recording deal with the Gramophone Company of London, controlled by Emil Berliner, a German-Jewish transplant who started his firm with Washington D.C. investment money. Caruso’s Gamophone recordings made him famous in London’s opera scene, not Continental Europe’s, and this is what lead Kahn to head-hunt him for the Met. (Kahn was also his minder; Caruso allegedly had wandering hands.)

One of the first operas Kahn wanted to stage was “Salome”, a work composed by one of the Strauss family and based on a play by Oscar Wilde about a Jewish erotic female dancer. Salome’s producer was Heinrich Conried, after whom the original Met operating company had been named. Conried, an Austrian, got his start at the Burgtheater in Vienna. (Conried also enjoyed patronage from Henry Morgenthau, Jacob Schiff and Daniel Guggenheim.) According to Kahn biographer Theresa M. Collins, Conried began rehearsals for Salome at a time when the Met’s Christian directors would be in church. Sexualization and offensive portrayals of John the Baptist lead Morgan interests to quash Salome’s New York City production.

Don’t miss the peaking nipples! Poster for the same work championed by Otto Kahn in NYC; Munich was a cauldron of heavily sexualized, violent theatrical content and its Elf Scharfricter troupe, the “Eleven Executioners”, actually inspired Vienna’s Cabaret Fledermaus.

Kahn’s patronage of the Met had to be more nuanced than his initial Salome foray, and during his time there he valiantly fought to bring Hapsburg talent to American shores, while indigenous NYC Met directors parried what they saw as German-Jewish takeover of the opera. Kahn would install Austrian set designer Joseph Urban at the opera, and later Norman Bel Geddes too, after having sent him to Austria for training. The Met would also house Kahn-divas like his mistress Maria Jeritza, whom he recruited from the Vienna State Opera.

A 1927 portrait of Maria Jeritza by Edward Steichen. Courtesy of the Smithsonian Institution/National Portrait Gallery.

In many respects Kahn’s musical patronage continued the espionage work which had begun with Flo Ziegfeld’s father. I detailed this likely Ziegfeld “soft power” operation in The Ziegfeld Cinema Corporation: Florenz’s father, Florence Ziegfeld, also worked with the Strauss musical family to bolster Northern/Boston cultural prestige via the Union Army’s musical corps in the wake of the US Civil War. (Frederick H. Prince’s father, Frederick O. Prince, was secretary of the Democratic National Convention and Boston’s leading Democrat politician during Ziegfeld’s Strauss/“Peace Jubilee” concert there in 1872.)

Elder Ziegfeld worked through his contacts in the Prussian Military to achieve this Strauss-partnership, but the Strausses were a prominent Viennese musical dynasty, so they would have operated with at least tacit approval from Franz Joseph. (Given Austria’s humiliating defeat by Prussia shortly before, the Strausses were probably cash-strapped too.) Besides the Salome debacle in 1908, after WWI Kahn again teamed up with the Strausses to recoup lost prestige for Austria in NYC.

Franz Joseph was aware of the power of Vienna’s musical culture to promote his family’s prestige, particularity after his devastating loss of power to Imperial Prussia in 1866. The Strauss family— the “Radetzky March” and “Blue Danube Waltz” people— were an ace in the pocket of the embattled emperor.

So far, I’ve only looked at Kahn’s high-brow cultural work, he was active placing Austrians in low-brow areas too. For example, his support of the Ziegfeld Follies (sets designed by Joseph Urban) and the avant gard theatrics of Max Reinhart, an Austrian who is best described as the second generation of “Jung Wien” literary rebels and a good friend of Berta Szeps Zuckerkandl.

I’ve listed a huge number of artists/agents-of-Kahn’s-influence: Kahn couldn’t have organized this many people alone and we know he didn’t. He had a separate secretarial staff which kept track of who got what money and under which terms. He also had at least two “capos” who steered useful talent to him: George Sylvester Viereck and Carl Van Vechten. These two men, urbane and of fluid sexuality, would hold celebrity parties and cultivate celebrity networks looking for careers for Kahn to finance. Van Vechten brought Kahn Norman Bel Geddes, as well as Paul Robeson and a host of “Harlem Renaissance” writers. In return for Kahn’s “friendship”, artists— particularly movie starlets— would make themselves sexually available to important men at Kahn’s parties, which were held at either his suite at the Ritz Hotel or in his Manhattan mansion. (This exploitative situation, a classic kompromat-factory, could be usefully compared to the modern Epstein operation and its Israeli connections.)

Louise Brooks was a Ziegfeld Girl and one of the few to dare to write about the sexual nature of Kahn’s work. As a social friend of William Randolph Hearst, her career faltered later in life. Brooks suffered from alcoholism and allegedly descended into less glamorous forms of prostitution.

Viereck was convicted as a German spy in the 1940s: he was an Oscar Wilde fan and socialist who took up service for the Nazis when the Ringstrasse money ran out. He did about three and a half years’ jail time and then wrote a book about it. Van Vechten’s stable of talent was probably too useful to be tainted by American counterintelligence investigations, though his literary output plummeted after the 1930s.

George Sylvester Viereck in the 1920s.

Carl van Vechten in the 1920s.

A third operative may also have helped Kahn: one “Lady Pat Russell”, who to the best of my current knowledge appears to be Bertrand Russell’s nanny-turned-third wife. Lady Russell, who went by the name “Peter” and smoked a pipe, was (according to Kahn biographer Collins) allowed to live rent free with her husband in Kahn’s house in Antibes as long as she arranged parties for Kahn there where he could discretely hook up with women. Lady Russell performed this roll well, if with some contempt for all parties involved, particularly the studied ignorance of Kahn’s close friends. This information comes from Theresa Collin’s biography of Kahn, and I have some reservations about whether it’s true and the exact identity of “Lady Pat Russell”, but there are good reasons it may in fact be so.

Lady Russell became sexually involved with Bertrand in 1930/31, as a 20-something Oxford student who happened to bump into the philosopher when he needed childcare (advertised?). In order for Theresa Collins’ information to be correct, Lady Russell had to have serviced Kahn over the 1928-35 period. It is worth nothing that Bertrand Russell was very close to the Ringstrasse Patron Wittgenstein family. Bertrand was the mentor-cum- PhD advisor at Cambridge University (a spy hotbed) of their heir Ludwig Wittgenstein, and was grooming Ludwig to be his successor. This cozy relationship continued over the 1910s and into the-early 1920s, including the period over which Ludwig fought in the Austro-Hungarian army. Bertrand Russell went to jail during WWI for his pacifism, which is something Emperor Franz Joseph would have appreciated. Later, Bertrand became a CIA asset during the 1950s “Congress for Cultural Freedom”, the agency’s ‘non-communist left’ astrotrufing initiative (of which the public is aware).

I believe this to be a photograph of Bertrand and Pat Russell, I will update this space as more info surfaces.

Kahn’s operation was severely tested by WWI. During the run-up to hostilities in 1911, the Scottish-Canadian press magnate Max Aitken (later Lord Beaverbrook) tapped Kahn to be a British member of parliament on Aitken’s behalf: Aitken’s “first political promotion” as he termed it. [See Collins, Otto Kahn: Art, Money and Modern Time.] Aitken’s enemies like Herbert Asquith would allege that the protectionist “tariff-reformer” stance of men like Aitken was really a pro-German stance. The genesis of this struggle was that British Shipping had lost leadership to that of Germany and adversely-affected London-based international businessmen were trying to steer the country into war on their own behalf. Herbert Asquith, once Prime Minister, set up what would become MI-6 in 1909 precisely to combat the “tariff reform” politics espoused by Aitken and deals typified by Aitken’s would-be puppet Kahn. [See Keith Jeffery, Mi6: The History of the Secret Intelligence Service, 1909-1949.] Kahn wisely decided the time was too late for a German Jew to transform into a pro-German British politician and stayed in NYC.

As 1917 approached, Kahn dutifully held to the Hapsburg line in the USA, which was to 1) promote pacifism (avoid American entry into the war as long as possible) and 2) preserve international culture-sharing (and financial!) networks. Evidence of this can be seen in Mutual Film’s Birth of a Nation (1915) and The Life of General Vila (1914).

Kahn’s stance was much more Austrian than that of the older partners at Kuhn, Loeb & Company, Max Warburg and Jacob Schiff, who were openly belligerent and pro-Prussian. The Warburg/Schiff stance was an attitude typical of Ringstrasse Patrons inside Austria-Hungary. (Max Warburg’s belligerent stance cost him his Federal Reserve Board seat.) When other Anglophile Met board directors wanted to cut the German opera offerings during the war, Kahn insisted this soft power channel be kept open. Where Kahn couldn’t promote German artists, he promoted French ones and therefore capitalized on bruised French feelings regarding their Anglo-American partners. [See Collins.] In September 1915— when Austria-Hungary was already militarily finished anyway— Kahn arranged positive Anglophone press for Emperor Franz Joseph via Ballet Russes dancer Vaslav Nijinsky’s release from prison in Hungary, which the aging monarch intervened personally to accomplish.

Vaslav Nijinsky dances ” Le Spectre de la Rose” in 1911. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Otto Kahn’s firm Kuhn Loeb & Company wanted to profit from both sides of the war. They made at least one crucial war loan to Austria Hungary at high interest rates, they did abstain from English war loans which would anger their German partners. At the same time, they wanted to make what loans they could to the Allies, too. Otto Kahn had a habit of picking up French loans that the Anglo-British set neglected, thereby irritating their French partners: Kahn did this with a decidedly Austrian “internationalist” flair.

Because of Kuhn Loeb & Co. two-facedness, pro-Anglo interests (chiefly Morgan interests) froze their one-time partners Kuhn Loeb out of some profitable ‘reparations’ deals at the end of the war, as well as other wartime financing. Kuhn Loeb & Co. did not enjoy the level of war profits they could have had given the prestige of their firm because of their double-dealing.

A more balanced person might accept lower profits as a generous response given the unethical nature of funding both sides of a war— when little people turn traitor, they’re shot. Not Otto Kahn. Otto Kahn took this loss of profit personally and responded by organizing a consortium of war-skeptic American businesses which would invest in the war indirectly and on both sides where possible. This company was called “The American International Company” (AIC), but they originally had planned to call it “The United Nations Corporation”. By “they” I mean AIC’s fathers, Otto Kahn, the British-German-Jewish financial magnate Ernst Cassel and National City Bank’s president Frank A. Vanderlip. Other investors included:

1) Armour & Co and it’s partner Union Pacific. At this time, Armour & Co was actually part of the “Beef Trust” umbrella company called “Central Trust Company”. This trust included Swift & Co. and controlled Union Pacific too. Kuhn Loeb & Co. money financed both the Central Trust and UP. Vanderlip’s National City Bank shared directors and management with Central Trust; Kuhn Loeb’s Jacob Schiff was a major Central Trust shareholder alongside Ogden Armour and the Swift clan.

2) General Electric/Westinghouse. GE was the ‘Morgan half’ to the “Electrical Supply Trust”, Westinghouse being the ‘Kuhn Loeb and Equitable Life Insurance half’. (Remember the Met’s James Hazen Hyde?) In reality, there was cooperation between Morgan and Kuhn Loeb through GE and Westinghouse: the two firms pooled their patents. It’s probable that the diversity of Boston and Pittsburgh banking interests in the trust gave Kuhn Loeb the upper hand after Westinghouse went into receivership and was reorganized in 1907. [See “The Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Company, the General Electric Company, and the Panic of 1907”. Niles Carpenter, Jr. Journal of Political Economy, Mar., 1916, Vol. 24, No. 3, pp. 230-253.]

3) International Nickel. The American half of a Canadian mining joint-partnership. INCO’s American money came largely from the Hicksite Quaker Joseph Wharton, a co-founder of Bethlehem Steel— that steel concern which Woodrow Wilson didn’t want profiting from WWI shipbuildling contracts. Many Hicksites converted to Unitarianism and even Mormonism, the cult which originated our first illegal British armament submarine contracts.

4) Anaconda Company. “Anaconda” was what was left over from the Amalgamated Copper Company, which had been part of John D. Rockefeller’s and Henry Flagler’s Standard Oil Trust. [Goetz historians will remember Flagler from Leon’s FL land speculations.] Standard Oil was broken up by Teddy Roosevelt in 1911, but Anaconda continued to be run for the Rockefellers by a wiley Irish duo, Cornelius Kelley and John Denis Ryan. The Guggenheim family, Kuhn Loeb & Co in-laws, were Anaconda’s “competitors” in the copper business, though they shared a joint enemy with Anaconda in F. A. Heinz, who I wrote about with regard to the post-WWI Paramount takeover.

5) American Telegraph & Telephone, a.k.a “AT&T”. This was a Roosevelt/Woodrow Wilson approved trust run by Theodore N. Vail, a D. C. political operative who married Post Office and Union Pacific Railroad interests, while making copper lines standard for the nation’s telegraph and telephone system.

6) W. R. Grace & Co. Originally an Irish chemical and shipping company based in Peru, it moved its headquarters in NYC at the end of the US Civil War. It specialized in chemicals for fertilizers and gunpowder. By WWI it was a shipping, crude oil and chemical conglomerate. The Graces were active in Catholic politics in the USA, like Thomas Fortune Ryan.

7) Robert Dollar Company. A Scotch-Canadian (like Max Aitken) shipping company which specialized in Pacific Ocean transport and US mail delivery. In the 1920s the Dollar family sold a portion of the firm to W. R. Grace & Co. In the run up to WWII, Franklin Delano Roosevelt seized the company’s shipping assets illegally, a situation which wasn’t ‘put right’ until the 1950s.

8) Stone and Webster. An engineering and construction firm which specialized in electrical utility management, and often shared interests with Westinghouse and GE.

A few things to point out about these companies:

A) They are largely controlled by Jewish or Irish interests, ethnicities which William Wesley Young’s British handlers identified as likely to be against the USA fighting WWI for Britain. Scottish merchants in the New World historically have been wary of English enterprises, which they saw as discriminatory against Scottish interests. A classic example being the fate of the Darien Expedition.

B) These companies had a strong South American presence, particularly the Graces and mining concerns. German interests found sympathetic ears in South and Central America for a long time.

C) These companies had formed strong relationships with the US Post Office Department. At the same time a similar synergy developed between investors sympathetic to Archduke Franz Ferdinand and the Austro-Hungarian postal system.

D) In the 1900s these companies were big donors to the Democrats, while the pro-war, anglophile, ‘Morgan’ crowd tended to give to the Republican Party. (This would change.)

What more can we say about Kahn’s AIC? Co-founder Ernst Cassel was a family friend of Kahn’s and a particularly valued connection by Kahn’s powerful in-law Sir George Lewis, who I will write more about in the future. National City Bank was one of the old New York City banks big enough to compete with Thompson’s and Baker’s National Bank of the City of New York, i.e. Arabut Ludlow’s benefactors.

Goetz fans know the Armour firm from its sponsorship of the mysterious pro-Prussian film magnate Col. Selig in the 1890s-early 1910s. Much like Col. Selig, by the early 1920s Armour & Co.— now part of Central Trust Company along with Swift & Co.— experienced credit problems and the Armour family’s stock was sold to Frederick H. Prince, a friend of Joseph P. Kennedy Sr.. (Prince’s father was Boston’s DNC rep when Elder Ziegfeld worked his Prussian military band magic with Strauss.) Prince busied himself removing political opposition to the “Beef Trust” by buying favor with Franklin Delano Roosevelt:

Excerpt from Ferdinand Lundberg’s “America’s 60 Families”, Vanguard Press, 1937.

Prince financed Joseph P. Kennedy’s takeover of RKO Pictures following Roosevelt interests’ cornering leading Jewish film executives in the notorious “Mishawum Manor” underage-prostitute badger trap. Prince’s heirs would own Armour/Swift/Central Trust Company (?) shares until the 1970s when the Prince holding was bought by the Greyhound Corporation, a shadowy investment vehicle based on the financially- and politically-troubled Greyhound Bus Company. Around the same time in 1972 the Swift part of the Swift/Armour/Central Trust Company (?) would be rebranded as “Esmark” and the infamous Franklin Federal Credit Union would be spun-off in the wake of these two “Beef Trust” changes. The “Franklin Scandal”— which also involves political extortion and child prostitution— had nauseating implications for both the CIA and the Republican Party apparatus in Washington D.C.

The ownership roster of the Armour/Swift/Central Trust Company after the 1930s is one of the most interesting and charged political questions in US Business History. What we can be sure of is that the trust’s owners and bankers were ‘with’ Otto Kahn and the AIC during WWI.

The goal of AIC was to “think internationally” and invest indirectly in Prussia-allied investments. This goal was effectively blocked by Morgan interests and AIC turned to ‘Allied-safe’ domestic American firms like the Pacific Mail and Steamship Company, the New York Shipbuilding Company, International Mercantile Marine Company and the Allied Machinery Company. Readers will remember some of these companies’ names from my explanation of American Red Cross involvement in Monroe, WI’s “Princess Theater”: all friends of Arabut Ludlow’s banking/counterfeiting partners…

Prior to the rupture of WWI, Otto Kahn’s buddies were good friends with Morgan interests, even with the Morgans’ lawyers White & Case!

The ‘humiliations’ experienced by Otto Kahn in the wake of WWI fundamentally undermined his and Kuhn, Loeb & Co’s place in NYC finance. Outfits like the Roosevelt-connected Dillion Read firm and Goldman Sachs rose to take their place. But, when November 1918 came, Kahn had spookier things to worry about.

After the unconditional surrender in November, Otto Kahn’s first point of business was to return to Austria “on vacation” and to do a little business. Whatever Kahn arranged bore fruit: in 1921 Kuhn Loeb & Co. bought the Creditanstalt bank. There were some stark realities for Ringstrasse Patrons to face as the remnants of Franz Joseph’s bureaucracy coalesced to form the ill-starred interwar government.

Ringstrasse clients who were ripped from the financial subsidies they enjoyed under Franz Joseph, yet who were not well connected enough in Vienna’s new (poorer) government, sought patronage from Lenin and Trotsky. Examples are Sabina Speilrein, Freud’s “early childhood education” protégé and Freud-protégé Adler’s patient, Adolf Abramovich Ioffe. Ioffe was a rich professional anarchist and a good friend of Trotsky, who made him chairman of the Military-Revolutionary Committee in Moscow, among other ambassadorial roles. In short, the Bolsheviks made up part of the funding which disappeared with the Danube Monarchy. (Speilrein would leave Moscow ignominiously under substantiated allegations that top party-members’ children, including Stalin’s, were systematically sexually abused in her kindergarten, see Etkind, Eros of the Impossible.)

Sabina Spielrein

Otto Kahn’s post-war art financing reflects this Soviet twist. This change should not be viewed as a ‘break’. The Ringstrasse Patrons were always supporters of socialism— after all, they made their money in government monopolies— and Russia’s grand new dawn seemed equally promising to Wall Street.

While characters like Spielrein and Ioffe brought the “avant gard” to Moscow, Otto Kahn promoted the “Russian Invasion of the American Theater” in New York City. Kahn-supported institutions included: The Ballet Russes, The Moscow Art Theater, and above all the Chauve Souris Cabaret, which seems to have taken inspiration directly from Vienna’s pre-war Cabaret Fledermaus. With eyes on the prize, Kahn also supported the post-1926 American-Russian Chamber of Commerce. It’s hard to overstate Kahn’s Bolshevik promotional activity:

In 1927, three Americans became honorary members of the Moscow Art Theatre: David Belasco, Morris Gest, and Otto H. Kahn. Belasco received the recognition for his commitment to excellence in the American theatre, whereas, Morris Gest and Otto Kahn earned it for successfully bringing the Moscow Art Theatre to America. This venture marked only one of the many contributions that Kahn and Gest made, both individually and together, to the American theater. Through their work in theatre and opera in New York, Gest and Kahn, a pair of unlikely collaborators, served as cultural ambassadors in the first three decades of the twentieth century. Both men repeatedly sought out foreign talent, and through sometimes difficult negotiations, one or the other had some involvement in arranging some of the most distinguished European artists and theatre companies, including Anna Pavlova, Michel Fokine, Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, Jacques Copeau, Max Reinhardt, the Habima Theatre of Moscow, the Moscow Art Theatre, Nikita Balieff’s Chauve-Souris, and Le Théâtre de Firmin Gérmier, to come to the United States. These artists and their performances contributed directly to the modernist transformations of the American theatre and to American’s perceptions of European and Russian performance in the early twentieth century. [Hohman, V.J. (2011). The Russian Invasion of the American Theatre. In: Russian Culture and Theatrical Performance in America, 1891–1933.]

[David Belasco’s family plays an important role alongside Kahn’s London uncle-in-law Sir George Lewis in establishing the modern “intelligence community”. More on that coming.]

Why might the owners of the Creditanstalt wish to promote Bolshevik-friendly art? Historians like Anthony Sutton write that American millionaires supported the Bolsheviks because they saw investment opportunities in the Tsar’s old assets— certainly those around Harvard’s Institute for International Development in the 1990s saw the same opportunities. Writers contemporary with the Creditanstalt purchase, like Mikhail Bulgakov and Leonid Andreyev, who was close to Henry Ford’s “Protocols of Zion”-supplier Herman Bernstein, came to the same conclusions. [Follow that link to see how William Wesley Young’s partner acted as a journalistic hit-man against Ford.]

‘Internationalism’, the forerunner of globalism, where capital and people can move unhindered around the globe, was always close to the hearts of the Ringstrasse crowd. Kahn’s role was to advertise this ideal through art, art being “the truest League of Nations,” as Kahn said. Biographer Collins:

Art brought him [Kahn] nearer to realizing an internationalist vision that Kahn articulated in 1916, when he warned of art’s vulnerabilities in the postbellum era if it were forced to compete with the vast material concerns of reconstruction. Granting that he had not expected the vacuum in postwar leadership, he had identified a “privilege and duty” for America— and himself— “to become a militant force in the cause and service of art, to be foremost in helping to create and spread that which beautifies and enriches life.”

Kah’s “postbellum” view of American artistic leadership perfectly reflects the Ringstrasse Patrons’ 1890s-onward interpretation of opportunities in the Anglo-American world. Families like the Wittgensteins would move to London, others to New England. Otto Kahn was still well placed to make their dreams reality in the 1920s.

Chauve Souris was not high art, like the Fledermaus it appealed to the local liberal elite, who were largely wealthy, largely artistically uneducated, and largely held in contempt by the company’s writers. Sex, violence and the absurd ruled. Much like Fledermaus toned-down the Munich Elf Scharfrichter’s gore for Viennese audiences; Chauve Souris toned-down the sex for American ones. Per Ringstrasse opinion, Americans can handle the circus. Collins:

As the revue returned the clown to theater’s “artistic calendar,” that sign of the reverence for commedia dell’arte in neoclassical modernism connected well with the potential artistic merits of America’s light theater, vaudeville and variety stages. Gilbert Seldes noticed the same point when praising Chauve Souris in his popular 1924 book, “The Seven Lively Arts”, which happened to carry a frontispiece by Ralph Barton, in the style of his curtain for the revue. Seldes joined the chorus of acclamation: “Here is something certainly vaudeville… appealing to every grade of intelligence… good music, exciting scenery, and good fun.” [Collins]

Chauve Souris Cabaret 1922 program. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

Besides being a vehicle for displaced Vienna-to-Moscow propaganda, Chauve Souris was a balm on Kahn’s offended post-war nerves. The cabaret offered Kahn a kind of rally; a regrouping for a second “Ringstrasse Offensive”, but this time in the New World:

As Otto Kahn gravitated toward the arts that were complex and collaborative, capturing the momentum of modernity, he drew himself nearer to those who were constantly on the cusp and who self-consciously created statements and agitations that once asserted and transcended the American character. Chauve Souris [“bat” in French, as “Fledermaus” is in German], a showy cabaret revue that appeared in New York during the early 1920s, captured this congregation most cleverly, when a painted curtain dropped between acts, and instead of brocade or velvet, the audience saw themselves caricatured by artist Ralph Barton. Titled “A Typical First Night Audience” when reprinted in slightly different version for Vanity Fair, the caricature was captioned, “Ingredients in the Mixed Grill of Metropolitan Life; A Social Panorama.” In each depiction, the celebrated banker-patron, Otto Kahn, sat conspicuously among more than one hundred select luminaries…

It is not without significance that Otto Kahn was in some way connected to a near majority of everyone in this scene. He was also the only international financier among these stars and celebrities, but more interesting was what this crowd meant to postwar modernity: they constituted a new internationalist elite… For that among several reasons, Chauve Souris may best illustrate the verve of Kahn’s patronage.”

The Ralph Barton caricatures described above are reproduced below. A complete list of the sitters, which might be interpreted as a list of undeclared foreign agents, is provided at the end of this post.

The Vanity Fair reprint of Ralph Barton’s Chauve Souris stage curtain caricature. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Of course, all this fêteing came to a dramatic end when the Rothschild bank, which Kuhn, Loeb & Co. bought in 1921, went bankrupt in 1931. Where was the financial wizard? Why could Otto Kahn not make dollars fall from the sky as he could prior to 1918? We won’t look too closely, but it seems that a type of self-realization overcame Kahn from the mid 1920s: he became depressed and introverted. He even remarked to his 23 year old lover Grace Moore that “We are living on the vitality of our forefathers and leaving very little to give the coming generation.”

Kahn’s patronage had become increasingly radical and increasingly disconnected from Europe’s cultural past. Much like the Frankfurt School elders and Sigmund Freud, he was underwhelmed by the modernity he helped to create. The Hapsburgs had been ‘raptured’, but again he was left out of the party.

I will stop here for today, but there is a considerable amount more to say about Otto Kahn and his “intelligence community” connections, which I will address shortly. I think that this post does go some way towards explaining why Monroe, WI was in the middle of so much Early Film spookery.

——————————————————————————

Kahn’s Chauve Souris crew:

Nikita Balieff, 1877 - 3 Sep 1936

Al Jolson, 26 May 1886 - 23 Oct 1950

John Emerson, 1874 - 1956

Anita Loos, 26 Apr 1888 - 18 Aug 1981

Irving Berlin, 11 May 1888 - 22 Sep 1989

David Belasco, 25 Jul 1853 - 14 May 1931

Lenore Ulric, 21 Jul 1892 - 30 Dec 1970

John Barrymore, 15 Feb 1882 - 29 May 1942

Michael Strange, 1890 - 1950

Anna Pavlova, 1881 - 1931

Josef Hofmann, 20 Jan 1876 - 16 Feb 1957

Reina Belasco Gest, ? - 1948

John Drew, 13 Nov 1853 - 9 Jul 1927

Theodore Roosevelt, Jr., 13 Sep 1887 - 12 Jul 1944

Maria Jeritza, 6 Oct 1887 - 10 Jul 1982

Giulio Gatti-Casazza, 3 Feb 1869 - 2 Sep 1940

Geraldine Farrar, 28 Feb 1882 - 11 Mar 1967

Mary Garden, 20 Feb 1874 - 3 Jan 1967

Elsie de Wolfe, 1858 - 1950

Arthur Brisbane, 12 Dec 1864 - 25 Dec 1936

Millicent Willson Hearst, 1882 - 1974

Henry Blackman Sell, 1889 - 1974

Condé Montrose Nast, 26 Mar 1873 - 19 Sep 1942

Irene Foote Castle, 7 Apr 1893 - 26 Jan 1969

Francis Welch Crowninshield, 24 Jun 1872 - 28 Dec 1947

Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney, 9 Jan 1875 - 18 Apr 1942

Kenneth MacGowan, 1888 - 1963

Alan Dale, 1861 - 1928

Ray Long, 1878 - 1935

Sam Bernard, 1863 - 1927

Marilyn Miller, 1 Sep 1898 - 7 Apr 1936

Ed Wynn, 9 Nov 1886 - 19 Jun 1966

Florence Jaffray Hurst Harriman, 1870 - 1967

Charles Dana Gibson, 14 Sep 1867 - 29 Dec 1944

Alexander Humphreys Woollcott, 19 Jan 1887 - 23 Jan 1943

Mrs. Lydig Hoyt, 1890? - 1930?

Franklin Pierce Adams, 15 Nov 1881 - 23 Mar 1960

Neysa McMein, c. 1880 - 1949

Matthew Heywood Campbell Broun, 7 Dec 1888 - 18 Dec 1939

Doris Keane, c. 1885 - 1945

Percy Hunter Hammond, 1873 - 1936

Moranzoni, 1880? - 1940?

Ann Haven Morgan, 1882 - 1966

Robert Burns Mantle, 1873 - 1948

Anne Harriman Sands Rutherfurd Vanderbilt, ? - 1940

Willard Huntington Wright, 1888 - 11 Apr 1939

S. Jay Kaufman, 1886 - 1957

Herbert Bayard Swope, 5 Jan 1882 - 20 Jun 1958

Walter Catlett, 1889 - 1960

Sophie Braslau, 1882 - 1935

Dorothy Gish, 1898 - 1968

David Lewelyn Wark Griffith, 22 Jan 1875 - 23 Jul 1948

Lillian Gish, 14 Oct 1893 - 27 Feb 1993

Elizabeth Marbury, 1856 - 1933

Leon Errol, 1881 - 1951

Zoe Akins, 1886 - 1958

Feodor Ivanovich Chaliapin, 13 Feb 1873 - 12 Apr 1938

Lucrezia Bori, 1887 - 1960

Frances Alda, 1883 - 1952

Maude Adams, 11 Nov 1872 - 17 Jul 1953

John Francis McCormack, 14 Jun 1884 - 16 Sep 1945

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin, 16 Apr 1889 - 25 Dec 1977

Marechal Joseph Jacques Cesaire Joffre, 1852 - 1931

Laurette Taylor, 1884 - 1946

Frances Starr, 1881 - 1973

Clare Consuelo Frewen Sheridan, 1885 - 1970

John Hartley Manners, 1870 - 1928

Albert Davis Lasker, 1880 - 1952

Samuel Lionel Rothafel, 9 Jul 1881 - 13 Jan 1936

Nicholas Murray Butler, 2 Apr 1862 - 7 Dec 1947

Ralph Barton, 14 Aug 1891 - 19 May 1931

Jesse Louis Lasky, 1880 - 1958

Edward Ziegler, 1870 - 1966

William J. Guard, ? - 1932

Louis Untermeyer, 1885 - 1977

Jacob J. Shubert, 1880 - 1963

Levi Lee Shubert, c. 1872 - 1953

F. Ray Comstock, 1880 - 1949

Morris Gest, 1881 - 1942

Oliver Martin Sayler, 1887 - 1958

Boris Israelevich Anisfeld, 1879 - 1973

Robert Edmond Jones, 12 Dec 1887 - 26 Nov 1954

Ringgold Wilmer Lardner, 6 Mar 1885 - 25 Sep 1933

Stephen Rathbun, 1880? - 1940?

Armand Veszy, 1880? - 1940?

Andrés de Segurola, c. 1873 - 1953

Gennare Papi, 1886 - 1941

Raymond Hitchcock, 1865 - 1929

Adolph Zukor, 7 Jan 1873 - 10 Jun 1976

Robert Gilbert Welsh, 1869 - 1924

Fay Okell Bainter, 1893 - 1968

Lawrence Reamer, 1880? - 1940?

Gertrude Hoffman, 1898 - 1955

Walter Johannes Damrosch, 30 Jan 1862 - 22 Dec 1950

Mary Nash, 1885 - 1976

Josef Willem Mengelberg, 1871 - 1951

Charles Darnton, 1870 - 1950

Otto Hermann Kahn, 21 Feb 1867 - 20 Mar 1934

Frank Andrew Munsey, 1854 - 1925

Florenz Ziegfeld, 21 Mar 1867 - 22 Jul 1932

Artur Bodanzky, 1877 - 1939

Adolph Simon Ochs, 1858 - 1935

John Rumsey, 1880? - 1940?

Ludwig Lewisohn, 30 May 1883 - 31 Dec 1955

George Simon Kaufman, 16 Nov 1889 - 2 Jun 1961

Lynn Fontanne, 6 Dec 1887 - 30 Jul 1983

Marcus Cook Connelly, 1890 - 1980

George Michael Cohan, 3 Jul 1878 - 5 Nov 1942

John MacMahon, 1880? - 1940?

Henry Edward Krehbiel, 1854 - 1923

Dorothy Benjamin Caruso, ? - 1955

Jacob Ben-Ami, 1890 - 1977

Dorothy Dalton, 1893 - 1972

David Warfield, 28 Nov 1866 - 27 Jun 1951

Robert Charles Benchley, 15 Sep 1889 - 21 Nov 1945

Karl Kitchen, 1885 - 1935

Antonio Scotti, 1866 - 1936

Fannie Hurst, 19 Oct 1885 - 23 Feb 1968

Hugo Reisenfeld, c. 1883 - 1939?

Vera Fokina, 1886 - 1958

Michel Fokine, 23 Apr 1880 - 22 Aug 1942

Avery Hopwood, 28 May 1882 - 1 Jul 1928

Constance Talmadge, c. 1899 - 1973

Anna Fitziu, c. 1886 - 1967

Reginald Claypoole Vanderbilt, 1880 - 1925

Frank Crane, 1861 - 1928

Jascha Heifetz, 2 Feb 1901 - 12 Dec 1987

Eugene Gladstone O'Neill, 16 Oct 1888 - 27 Nov 1953

Nicholas Konstantin Roerich, 10 Oct 1874 - 12 Dec 1947

Joseph Urban, 1872 - 1933

Arthur Hornblow, 1865 - 1942

Paul Meyer, 1880? - 1940?

Elsie Janis, 1889 - 1956

Paul Block, 1877 - 1941

John Chipman Farrar, 1896 - 1974

Sergei Vassilievich Rachmaninoff, 2 Apr 1873 - 28 Mar 1943

Herbert Clark Hoover, 10 Aug 1874 - 20 Oct 1964

John Golden, 1874 - 1955

Winchell Smith, 1871 - 1933

George Jay Gould, 1864 - 1923