Havana Syndrome and Daniel Schreber

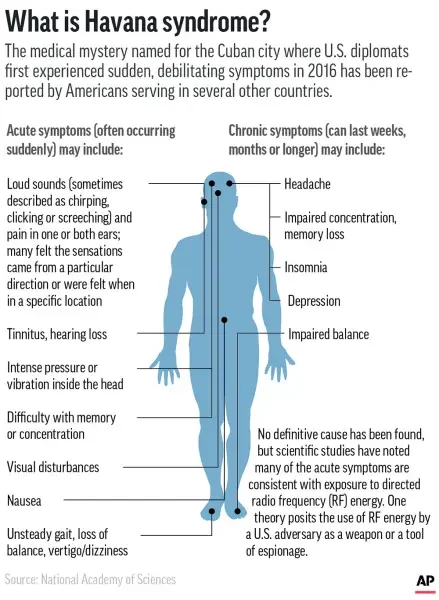

“Havana Syndrome” is believed to be a type of poisoning: poisoning by microwave radiation. Since 2016 at least, US intelligence operatives, often CIA men, have been coming down with symptoms of microwave radiation poisoning. They believe that they are being targeted by Chinese, Cuban and Russian agents with portable high-intensity microwave devices. Here are the symptoms:

From the New York Post.

When I first read about those symptoms a year ago, it made me very uncomfortable. The symptoms corresponded with those described by Judge Daniel Paul Schreber during his second period of mental illness, an illness which suddenly appeared in October 1893 after eight years of good health. Schreber is famous because of Sigmund Freud’s (second-hand?) psychoanalysis of him in 1911 titled “Psycho-Analytic Notes on an Autobiographical Account of a Case of Paranoia (Dementia Paranoides)”, and also because of Schreber’s own 1904 autobiography Denkwuerdigkeiten eines Nervenkranken a.k.a. Memoirs of my Nervous Illness. Here is Schreber’s account of what started his second period of illness:

“The first really bad, that is to say almost sleepless nights, occurred in the last days of October or the first days of November [1893]. It was then that an extraordinary event occurred. During several nights when I could not get to sleep, a recurrent crackling noise in the wall of our bedroom became noticeable at shorter or longer intervals; time and again it woke me as I was about to go to sleep…”

This repeated exposure to the “crackling noise” from the walls, which he only heard at night in bed, lead to extreme insomnia, anxiety, depression and suicidal thoughts for which Schreber was hospitalized. He also experienced nausea; circulation trouble so that “walking up only a moderate incline caused attacks of anxiety”; memory problems; and visual disturbances. Schreber heard the crackling after his hospitalization too, but he doesn’t elaborate on where. [Schreber, Memoirs of my Nervous Illness, p 47. 2000]. Again, the overlap with “Havana Syndrome” is marked.

The first question that came to my mind was: “Could microwave radiation be manufactured in 1893?” The answer is yes, microwave radiation was first officially generated and recorded by Heinrich Hertz in 1887 using his induction coil and Leyden jar experiment. However, brilliant minds had been mulling over electricity and its medical properties for a long time by 1887. The 1820s saw Hans Christian Ørsted and André-Marie Ampère identify elecromagnetic forces’ effects on wires and magnetic fields; and magnetism had been used in (quack) medicine for decades. That a clever German doctor might investigate the effects of moving wires near the body is not such a profound step... especially if the research funders cared more about on-the-ground effects than ‘unified theory’ explanations like Maxwell’s.

The correspondence of two sets of symptoms does not prove those symptoms are caused by the same thing. However, there is more to Schreber’s story and the political history of the nations using these weapons which makes the case that Schreber was initially attacked with EMF radiation stronger.

It is important to note that Schreber’s second illness didn’t happen in a vacuum. Schreber had come to the attention of Dr. Paul Flechsig in 1884 after his first mental illness: a bout of depression following his electoral defeat in Chemnitz that year. Schreber, a local judge from a celebrated liberal German family, was the conservative “National Liberal” candidate running against the Jewish socialists.

This is how Freudian author Zvi Lothane characterized the 1884 electoral situation:

The party [National Liberal] was promoting worker’s rights, such as health and sick-leave insurance— though more in appearance than in substance, for it was simultaneously supporting the continuation of Bismark’s repressive antisocialist laws as protection against unrest and revolution. Schreber’s campaign thus stood against radical socialism. Constituting a symbolic presence in the campaign were the Jewish socialists, the founders Marx and Lassalle, and many lesser-known adherents in Germany. By 1890 there were 953 Jews in Chemnitz, and while we have no knowledge of what they felt about Schreber’s candidacy, we know from his remarks in the Memoirs something about what Schreber Paul [sic] felt about the Jews.

Schreber’s party and like-minded citizens promoted him in huge advertisements on the pages of the local newspaper. A second editorial, favoring Paul [Schreber], was printed on October 26, two days before the election day. All this was to no avail: the socialists won in Chemnitz by a sweep, whereas in most of the surrounding districts the National Liberals, favoring Bismark’s policies both at home and abroad, carried the day.

It was Goliath who won; Schreber may have felt he was defeated by the Jews and the Catholics. In fact, the election was a crushing defeat for him.

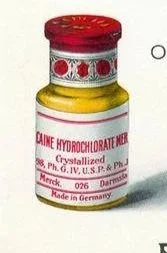

It was a tragedy for Daniel Paul Schreber to have chosen Dr. Paul Flechsig as his physician in 1884 because Paul Flechsig inspired and fascinated Sigmund Freud, at that time a cocaine- dealer and mental health analyst to Vienna’s Ringstrasse. [Freud was contracted by Merck, Europe’s only cocaine manufacturer.]

Sigmund Freud came from a Galician family of currency counterfeiters and, according to the work of historian Peter Swales, human traffickers for the sex trade. The Freud family background was typical for upper-middle-management of the Galician Gang, which probably explains why the Ringstrasse Patrons, the shadlanut intercessors for the Galicians, trusted Sigmund Freud. Indeed Freud’s circle included many prominent socialists who would take power in the USSR following the Russian Revolution. Freud and his circle also saw the Viennese medical community as a field to be conquered for their vision of ‘Jewish Interests’. German Liberals like Daniel Paul Schreber were the enemy.

Readers may be interested in the Allan Ginsberg/James Jesus Angleton conflict which rocked the CIA from 1950s-1973.

Whatever the source of the insomnia-inducing clicking sound, Schreber’s ‘nervous illness’ was compounded by Flechsig’s treatments. Flechsig administered a regimen of opiates and sodium bromide designed to “shock” Schreber’s nerves back to health. These chemicals, along with the abuse Schreber suffered at the hands of asylum staff (isolation, physical, sexual and psychological abuse) must have contributed to Schrebers “religious” experiences, perhaps better described as hallucinations, which Schreber began to have under Flechsig’s “care”.

I stress that Schreber was not “psychotic” when he was checked in that October. The visions happened only after weeks in Flechsig’s hospital, under conditions which would mentally break the strongest man. (And increase his suggestibility and encourage dissociation.) Prior to that fateful October clicking, Schreber was a respected legal mind whose judicial career went from strength to strength. He had just been appointed president of the court at Dresden and moved into a new home there when the “clicking” started. Previously he’d held important judgeships in Chemnitz, Leipzig and Freiburg.

Schreber’s new-found religiosity under Flechsig is equally disturbing. While Schreber’s family background was Protestant Christian he was not a particularly religious person. In fact his family were famous for its scientific focus: his father was physician Daniel Gottlieb Moritz Schreber (1808-1861); his paternal great-grandfather was economics professor and cameralist Daniel Gottfried Schreber; and his uncle was the famous collaborator with Carl Linneaus, Johann Christian Daniel von Schreber. The Schreber family was a product of the Enlightenment.

Despite his luke-warm religious views, under Flechsig’s care and possibly that of an unidentified “Jewish” doctor, Schreber began to have Kulturekamp-style religious visions that strangely echoed the infighting which racked Sigmund Freud and his Vienna followers.

Let me put that in context with some background: after Freud’s failure to secure contracts from the Austro-Hungarian military in 1918, the old Austrian regime fell and Freud had to look for new sources of patronage. The Fifth International Psychoanalytic Conference in Budapest was specifically designed to sell psychoanalysis as a “war neurosis” treatment to the “Austro-Hungarian war command” through a network of well-placed Jewish military doctors lead by Sandor Ferenczi. (Psychoanalysis would have replaced electroshock therapy, which was the military’s primary interest, cough cough.) When the Hapsburg’s well dried up, Freud turned to the Bolsheviks, among other sources, for funding for his network. These Bolsheviks were heirs to the socialists who Schreber ran against in Chemnitz.

Julius Wagner-Jauregg was the Austrian Military’s electroshock therapy contractor, a position Freud dreamed of usurping. Both men played an important role as mental health expert witnesses for the state in high-profile criminal cases, too.

Freud’s Bolshevik connections are the subject of Alexander Etkind’s book Eros of the Impossible, which I recommend to all readers. Men and women of Freud’s circle looked to the Bolsheviks for patronage, per Etkind:

In the earliest years following the Bolshevik revolution, Muscovite [psycho]analysts were supported and employed in the country's highest political circles, most intensively by Leon Trotsky, whose interaction with psychoanalysis we will examine more closely in chapter 7…

Freud followed the chain of events in Soviet Russia intently, at first with hope, then fear, and finally desperation and revulsion. At pains to dispel the understandable impression that his ‘Future of an Illusion’ was inspired by the Soviet experience, Freud wrote in 1927, “I have not the least intention of making judgements on the great experiment in civilization that is now in progress in the vast country that stretches between Europe and Asia.” But just three years later he confessed to Arnold Zweig that the events taking place in that immense nation presented him with a problem of personal significance “What you say about the Soviet experiment strikes an answering chord in me. We have been deprived by it of a hope-- and of an illusion-- and we have received nothing in exchange. We are moving toward dark times. I am sorry for my seven grandchildren.” Among those with whom Freud discussed Russian issues over the decades was his patient and co-auathor William Bullitt, the first US ambassador to the USSR. Bullitt, in turn, left his unmistakable imprint on Mikhail Bulgakov's ‘The Master and Margarita’, as the reader will see in exploring with me the intertwining lives of Freud, Bullitt, and Bulgakov, in a new interpretation of this novel.

In addition to Bullitt, Freud’s disciples Sabina Spielrein and Adolf Abramovich Ioffe, one of Trotsky’s rich “professional guerrilla” friends from Vienna, found state succor with the Bolsheviks. Russian psychoanalysists blessed by Freud ran Moscow’s “Orphanage-Laboratory” which educated leading party members’ children— including Stalin’s son— and which was closed for systemic child molestation. In fact, according to Isidor Sadger, in 1907 after Alfred Alder’s courting C.G. Jung at the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society, the society was more likely to take in Communist Party members than medical doctors. [Sadger, Recollecting Freud, p 57.]

The billionaire-funded “Riot Inc.” is an old political tactic from Austria-Hungary’s cosmopolitan “new aristocracy”, see Etkind’s Eros of the Impossible.

The narrow ethnic squabbling of Freud’s Jewish disciples was a topic that Anglosphere promoters like Ernst Jones fought hard to cover up because the squabbling framed Freud’s ideas in terms of ethnic warfare, not in terms of a heath panacea which would bring influence and big bucks. A glimpse behind the curtain came in 2005 when Alan Dundes of the University of Wisconsin located a copy of Isidor Sadger’s suppressed 1930 autobiography, Recollecting Freud, in a Japanese University and surreptitiously duplicated it. Sadger was one of Freud’s most loyal, prolific and long-serving Viennese acolytes. In the biography Sadger describes Freud’s intention of capturing the Western medical community for Jewish interests:

In vain, Freud tried to persuade us: “They [non-Vienna psychoanalytic societies] are all ten years ahead of us in terms of practical experience (this was the bonbon in order to win us over, given with the pretense of being reluctantly acknowledged). So long as psychoanalysis has its center in Vienna, it will always be considered a Jewish science and will never be able to conquer the clinic.” [p. 78].

[P. 96] When later a large number of Christians joined, they either moved away from Jewish teachings [“Jewish sexuality”] like the Swiss group under C. G. Jung or they did not accomplish anything significant. I cannot believe it was just the rarity of Christian disciples that induced Freud to make every single one of them his most special favorite. Yet the fact is that one such Christian follower was liked far more than ten of the Jewish ones.

Sadger, and other Jewish Freudians, were jealous of Freud’s relationship with the gentile Jung. Sadger’s entire biography frames the Freudian cult in terms of an “us” vs. “them” battle between Jewish and Christian doctors in Vienna. Sadger explains:

[p 98] I [Sadger] have already in earlier chapters detailed how he [Freud] showered Jung with credit, praised him for discoveries which he [Freud] himself had made, and finally at the Nuremberg congress, without further ado, he was ready to give his whole young discipline to the Christian clinic. Here I must enlarge upon my previous report. While the Viennese [Jewish] students were stormily objecting to such suicide, and were discussing their very next steps in a side-room, the Professor [Freud] appeared, uninvited, among them, and spoke with fierce agitation: “You are for the most part Jews and for that reason you are not suited to make friends for the new teachings [Freudian psychoanalysis]. Jews must resign themselves to being cultural dung. I must find a connection to the academy! [Emphasis added by Sadger.] He, of course, never achieved the hoped-for connection to the Christian scientific establishment and such a connection would still not have happened even if the Christianization of psychoanalysis had not failed due to the objections of the Viennese students. Yes, I even dare to make the following claim: had Freud died two decades earlier, then he himself and his entire teachings in spite of all his enormous genius, would have become nothing more than mere cultural dung for the Christian scientific establishment and its representatives. Some sort of privy councilor or unknown public health officer would then have again revived psychoanalysis—obviously in a suitably proper recast form— and at most named Freud as one of its pioneers.

Here is where this ethnic malice became deadly for Schreber: the only reason Freud brought Sadger into his orbit was because in 1897 Sadger had cultivated Schreber’s doctor, Paul Flechig, with a flattering article: you can read the first English translation of “The Thinking Protein (1897)” here. Freud saw Sadger as useful vis a vis Flechsig. 1897 would have been the midpoint of Schreber’s committal when Flechsig had him transferred to the Sonnenstein State Asylum under a Dr. Weber. (Flechsig had Schreber moved around a lot.)

Freud wanted to emulate Flechsig’s renoun. This worm ate at Freud for fifteen years, and in 1911, the year of Schreber’s death, Freud published an analysis of Flechig’s patient based on Schreber’s 1904 Memoir of my Nervous Illness. (After a flurry of initial excitement in 1904 the medical community lost interest in the memoir.) Freud’s strangely belated publication on Schreber only appeared in 1911, the year of Schreber’s death. Why so late?

In 1902 Schreber had his power of attorney restored and was given a clean bill of mental health by state authorities. When he published his memoirs two years later, he accused Flechsig of using him for psychological experimentation via suggestion in an open letter to the doctor at the beginning of his book. Schreber writes in this open letter:

As remarked at the end of Chapter 4 and the beginning of Chapter 5 of the “Memoirs”, I have not the least doubt that the first impetus to what my doctors always considered mere “hallucinations” but which to me signified communication with supernatural powers, consisted of influences on my nervous system emanating from your [Flechsig’s] nervous system…

There would then be no need to cast any shadow upon your person and only the mild reproach would perhaps remain that you, like so many doctors, could not completely resist the temptation of using a patient in your care as an object for scientific experiments apart from the real purpose of cure, when by chance matters of the highest scientific interest arose.

The “hallucinations” in question sound like they could have come from the mind of Isidor Sadger. For instance, Memoirs p 56:

The number of points from which contact with my nerves originated increased with time: apart from Professor Flechsig, who was the only one whom for a time at least I knew definitely to be among the living, they were mostly departed souls who began more and more to interest themselves in me.

In this connection I could mention hundreds if not thousands of names, many of which I learnt later, when some contact with the outside world was restored to me through newspapers and letters, were still among the living; whereas at the time, when as souls they were in contact with my nerves, I could only think they had long since departed this life. Many of the bearers of these names were particularly interested in religion, many were Catholics who expected a furtherance of Catholicism from the way I was expected to behave, particularly the Catholicizing of Saxony and Leipzig; amongst them were the Priest S. in Leipzig, “14 Leipzig Catholics” (of whom only the name of the Consul General D. was indicated to me, presumably a Catholic Club or its board). The Jesuit Father S. in Dresden, the Ordinary Archbishop in Prague, the Cathedral Dean Moufang, the Cardinals Rampolla, Galimberti and Casati, the Pope himself who was the leader of a peculiar “scorching ray”, finally numerous monks and nuns; on one occasion 240 Benedictine Monks under the leadership of a Father whose name sounded like Starkiewicz, suddenly moved into my head to perish therein. In the case of other souls, religious interests were mixed with national motives; amongst these was a Viennese nerve specialist whose name by coincidence was identical with that of the above-named Benedictine Father, a baptized Jew and Slavophile, who wanted to make Germany Slavic through me and at the same time wanted to institute there the rule of Judaism; like Professor Flechsig for Germany, England and America (that is mainly Germanic States), he appeared to be in his capacity as nerve specialist a kind of administrator of God’s interests in another of God’s provinces (the Slavic parts of Austria); because of this a battle arose for a time between him and Professor Flechsig through jealousy as to who was to predominate.

We know very little about whom Schreber was exposed to under Flechsig’s care, but Freud’s interest in Flechsig is ominous. Also ominous is the fact that Freud, a publicity-chaser, would only publish on Schreber seven years after the Memoirs’ launch and once Schreber was dead and couldn’t remember anything more or answer Freud. Freud’s Schreber essay came out at the onset of Freud’s putsch to become a military contractor for the Austro-Hungarian Army and at the urging of A. A. Brill, an Austrian military man himself and NYC “Education Film Board” partner to Monroe, WI native William Wesley Young. [See Lothane, p. 11]. Freud’s main military sales pitch, the “narcissism” concept, was rushed to publication following the exposure of double agent Col. Alfred Redl.

Abraham A. Brill, one of the earliest personalities covered on andreanolen.com and a shadowy force in US history.

So with Schreber we have a man who believed he was subject to surreptitious psychological tests from a doctor who courted military contractors with both Soviet and Galician Gang connections. Only in 2025 can the public associate some of Schreber’s experiences with energy weapons… or could we have made the connection sooner?

It turns out that in 1985 Dr. Robert O. Becker, a Director of Orthopedic Surgery at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Syracuse, New York, wrote a book titled The Body Electric which details joint Soviet-American research into energy weapons almost exactly like those used in “Havana Syndrome” [p 315]:

Apparently this [Soviet] concern [for microwave poisoning] doesn’t include Americans, for the Soviets have been bombarding our embassy in Moscow with microwaves for some thirty years. In 1952, at the height of the Cold War, there was a secret meeting at the Sandia Corporation in New Mexico between U.S. and U.S.S.R. scientists, allegedly to exchange information on biological hazards and safety levels. It seems the exchange wasn’t completely reciprocal, or perhaps the Americans didn’t take seriously what the Russians told them; there have been other joint “workshops” since then, and each time the Soviets have sent people who publicly acknowledged the risks, while the Americans have always been “no-effect” men. At any rate, soon after the Sandia meeting, the Soviets began beaming microwaves at the U.S. embassy from across Tschaikovsky Street, always staying well within the Schwan limit. In effect, they’ve been using embassy employees as test subjects for low-level EMR experiments.

The strange thing is that Washington has gone along with it. The “Moscow signal” was apparently first discovered about 1962, when the CIA is known to have sought consultation about it. The agency asked Milton Zaret [a microwave radiation expert from the curious community of Scarsdale, NY where William Colby settled after WWII and from where Peter Citron ran to Nebraska] for information about microwave dangers in that year, and then hired him in 1965 for advice and research in a secret evaluation of the signal, called Project Pandora. Nothing was publicly revealed until 1972, when Jack Anderson [a CIA “Family Jewels” concern] broke the story….

It turns out that the embassy staff were affected by the immune system degradation and “chromosome breaks” one would expect from microwave poisoning: “The Embassy staff had to learn this when the rest of us did— in the newspapers nearly a decade later”. Becker explains the US government’s decades-long reluctance to admit the dangers of microwave radiation as due to the repressive interests of the military-industrial complex.

The US Navy has been at the forefront of designing energy weapons, these were practical for use against crowds by 1973. Becker goes on to describe that “clicking”, readers:

In the early 1960s Frey found that when microwaves of 300 to 3,000 megahertz were pulsed at specific rates, humans (even deaf people) could “hear” them. The beam caused a booming, hissing, clicking or buzzing, depending on the exact frequency and pulse rate, and the sound seemed to come from just behind the head…Later work has shown that the microwaves are sensed somewhere in the temporal region just above and slightly in front of the ears… That the same effect can be used more subtly was demonstrated in 1973 by Dr. Joseph C. Sharp of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Sharp, serving as a test subject himself, heard and understood spoken words delivered to him in an echo-free isolation chamber via a pulsed-microwave audiogram (an analog of the words’ sound vibrations) beamed into his brain. Such a device has obvious applications in covert operations designed to drive a target crazy with “voices” or deliver undetectable instructions to a programmed assassin.

Perhaps we’ve found the source of Schreber’s “rays” through which Flechsig’s “nerves” worked on Schreber and which talked to him about Freud-circle ethnic conflicts? Becker’s book also puts into context the reluctance of modern intelligence officials, like Avril Haines (scion of the Galacian Gang per her father); or like Elbridge Colby (grandson of Galican Gang partner, CIA head and Franklin Scandal suppressor William Colby) to either acknowledge the “Havana Syndrome” attacks or identify who is accountable for their cover-up.

The same names just keep on popping up, don’t they?