Rainer Hapsburg, The "Bicycling" Archduke?

Every family has its black sheep. Sometimes, however, the person identified as the “black sheep” isn’t so much an outlier, but rather a representative of widely-held family characteristics that his relatives don’t wish to acknowledge. Archduke Rainer of Austria (1895-1930) was an example of the latter kind of “black sheep” and it’s his questionable dealings in Vienna’s early film industry which I will examine today.

Archduke Rainer came to my attention because of the following press clipping:

New York Times, May 26th 1930

Now, what the NYT describes above sounds an awful lot like a form of film theft which contemporaries of Archduke Rainer called “bicycling”. Historian of film piracy Kerry Seagrave describes “bicycling” this way:

Another group the motion picture producers had to watch out for were the exhibitors, the theater owners and managers. For the most part they engaged in a different kind of stealing from Hollywood than that performed by the print stealing pirates, although cinema employees were often key access people in those rings. At the level of theater owner and management, the stealing was different. One of the most popular scams engaged in by exhibitors was the practice known in the trade as “bicycling”. An exhibitor who had rented a film legitimately for a specified period of time, say, for one week at a fixed sum of dollars, would try and screen the print for an extra day or two at the beginning or end of his run. Or the cinema owner would rent the movie for one of his theaters and then screen it illegally at another theater he owned. Or two exhibitors would each rent half as many films as they needed for a full program and then swap the movies back and forth each night, giving each a full program for half the price. In some cases reels of films were sped one by one to a second theater after they finished screening in one venue. Sometimes this was done by bicycle messenger. As early as 1915 exhibitors were reported to be engaged in bicycling. Several New York City exchanges, according to one account, tolerated the practice-- if they were informed before the event and consented. In those cases they charged 25 percent over the contracted price.

There are three parts to Seagrave’s observation above that I’d like to explore a little further. First of all, “bicycling” took many forms, for instance public transport could be used by runners to the same end. Felix Feist, a representative of Southern US film exchanges, reported this variant in the April 15th 1916 edition of Motion Picture News:

Motion Picture News, April 15, 1916.

If one had the capital to invest in a fleet of motorcycles to effect the same ends, one might “bicycle” more efficiently and over a far wider area than the poor sops who peddled, bused or employed street urchins to run film reels back and forth. A man skilled in the maintenance of said motorcycles would have an economic advantage over competitors who would have to hire in mechanical expertise.

The problem with bicycling from an exchange’s standpoint is that they, the film exchange, are not being compensated for the wear on the film incurred through multiple showings. This wear was significant because film was delicate. When exchanges were compensated for the extra wear, they had little reason to be concerned about multiple showings, provided the film was returned on time. If Archduke Rainer was running his motorcade in the service of a syndicate of theater owners/operators who had contracted with the exchanges to pay for every showing of the films, then what the Archduke was doing was not unethical and should not be described as “bicycling”. For economic and legal reasons, I think that this hypothetical situation is unlikely.

A picture of Archduke Leopold and Archduke Rainer, prior to 1918. (Left to Right) The brothers were ‘joined at the hip’ as we say in the Midwest.

What are these economic and legal reasons? In the 1920s, economic conditions for most people in former Austro-Hungarian lands were bad and exhibitors had powerful incentives to cut costs, especially when those costs had to be paid according to an industry priced in American Dollars, which then disappeared overseas. Rainer himself had very expensive habits, and since he, like most of his family, had not managed his estates in the most profitable way, cash was tight. Rainer’s only acknowledged source of income in Vienna was a mechanic’s shop which he owned. In addition, Rainer and his younger brother Leopold faced impossible demands for money from their financially irresponsible mother, who lived in Spain with the rest of the family.

Rainer Hapsburg had expensive hobbies: “On a Daytona Beach record-breaking Indian, Kellner won the historic Semmering hill-climb for 1921. He is shown at speed on one of the many curves on the course. A pre-war 3½hp Triumph, driven by the Archduke Rainer Hapsburg, was first in the 500cc class after a keen tussle with several post-war German machines.” Courtesy of MotorcycleTimeline.com

Archduke Rainer had legal problems, too. In 1921— the same year as the flashy motorbike race pictured above— Rainer was arrested for passport forgery.

New York Times, August 24th 1921. Archduke Rainer is usually referred to as “Rainer Karl”, the “Salvator” printed here was often used by the press— possibly a repeated error.

While it was diplomatic for the NYT to speculate on what Rainer was “probably” trying to do under a forged passport, papers in Graz, the nearest German-speaking city to Laibach, were not so kind. Graz papers often punched above their weight on intelligence matters, because Graz was the base for leading Austro-Hungarian intelligence/law enforcement experts and the training ground for the empire’s military intelligence elite.

Neues Grazer Tagblatt, August 24th 1921.

The above clipping reads:

Apprehension of a former Archduke.

Corresp. Laibach, 22nd August: Yesterday the former Archduke Rainer Salvator was apprehended, in the company of his father-in-law, the Baron Nikolits, and his brother. He was using a forged passport. Rainer Salvator is the son of the former Archduke Leopold Salvator, who is presently staying in Spain. He is 26 years old and married Miss Nikolits shortly after the coup.

There are a couple of bombshells about this Graz reportage: that Rainer was married is, in my experience, never mentioned in histories. Bertita Harding makes no mention of it in her history of Rainer’s immediate family, “Lost Waltz”. If it was Rainer who actually married this women, the silence (or obfuscation) from his family is probably because the match was embarrassing. Harding does claim that Archduke Leopold made an “adolescent romance” match with Baroness Dagmar Nikolitch-Podrinski, who was a cousin of “concert artist” Muk de Jari, a match which the family frowned upon. Muk de Jari was a film actor in the 1920s.

Film actor Muk de Jari courtesy of cyranos.ch

Rainer chose to stay in Vienna and renounce his title when his family fled to Spain— his family advised against this and the whole renunciation affair smacks of ‘Louis Égalité’-type political posturing. Rainer’s younger brother Leopold, who also chose to stay with him in Vienna, felt no need to renounce his title. That Leopold kept his title is strong evidence that Harding is right here and that it was Leopold who briefly married Dagmar ‘Nikolits’. However, Harding also records that Leopold, instead of Rainer, ran the ‘bicycling’ business, which I believe is misleading if not outright wrong. This argument is somewhat academic though, because both Leopold and Rainer were apprehended by police when Rainer tried to use a fake passport with the ‘father-in-law”. The brothers were joined at the hip.

Who were this Nikolits family that ‘Rainer Hapsburg’/Archduke Leopold married into just after the ouster of their imperial house?

Dagmar Freifrau von Wolfenau, born Baroness Dagmar von Nikolić-Podrinska in Zagreb, Croatia.

I was able to find no information on the “Nikolits” family, but it seems the Baroness von Nikolić-Podrinska was the daughter of a road-runner (Styrian-turned-Italian-turned-Hungarian) noblewoman and the scion of a common Croatian family who was inducted into the nobility during the corrupt time of Maria Theresa’s son Joseph II. It wasn’t uncommon for the seediest elements of Central European society to seek out embattled nobility for the social prestige of a title, examples being the case of Fritzi Massary and Frédéric Prinz von Anhalt. That this “Baron Nikolits” would wish to accompany Rainer while using a forged passport suggests the other Hapsburgs probably had good reason not to acknowledge him.

What we can say is that Laibach, now called Ljubljana, is in Slovenia— always a hotbed of slaving— and that post-WWI passport controls are recognized as one of the first real hurdles faced by the very profitable Galician network. Certainly, Leon Goetz’s pornography business partner/pimp Sint Millard was interested in the von Nikolić-Podrinskas’ home country Croatia during the post-WWI troubles that racked Balkan lands. Given Rainer’s questionable film activities, given his money troubles, given his/his brother’s low ‘revolutionary’ marriage, and given the criminal connections nurtured by generations of his family which I will describe presently, I think it’s reasonable to look at Rainer’s passport forgery in a dark light. Whatever Rainer’s motivations, the passport incident could only have compounded the pressure on him to make money fast. On that note, let’s return to the Kerry Seagrave’s discussion of “bicycling”.

Seagrave points out that exchanges had no legal standing against “bicycling” in places where copyright law and contract law are not sufficiently developed to protect the perceived rights of exchanges and film producers. The US had not signed onto the 1886 Berne Copyright Convention which protected intellectual property in Europe, so the legal standing of US film copyright holders and by extension the film rental concerns in Europe was gray. (Why no signature? American publishers were notorious thieves of literary works.) This ‘legal grayness’ was especially true in former Austro-Hungarian lands, where copyright law was less stringent than in other European locales. In fact, the first press-mentioned instance of bicycling I could find was actually in Hungary in 1913 (see the second part in the excerpt below):

Motion Picture World, April 1913. Foreign News section.

In the excerpt above, readers will see (from the first half) that “Every license [to exhibit films] in Vienna is revocable at the pleasure of the police, without any remedy whatever.” Austro-Hungarian film exhibitors operated at the will of the police, just as Austro-Hungarian bordellos did, thanks to the Hapsburg policy of making prostitution illegal, but tolerated at the will of the police. Because of this policy of toleration, the police were forced to go into business with the pimps, whether they liked it or not. In some cities, like Budapest and Trieste, the pimps were indistinguishable from the police, while in other places like Graz and Vienna, the police/pimp partnership was a more fraught one. Why would the Archduke’s family adopt such corrosive policing policies?

The answer: political instability. Readers will notice that the pimp/police collusion phenomenon was strong in Austro-Hungarian regions that were prone to rebellion. This was the result of at least one century of Hapsburg political policy. In his book “The Revolutionary Emperor: Joseph II of Austria”, author Saul K. Padover notes that Maria Theresa (Joseph II’s mother and sometime co-regent) exercised a policy of sending troublesome Viennese prostitutes to the capital of Hungary, Budapest. The rationale for such sponsorship of commercial sex is something I discussed in my post The US Navy, Organized Prostitution and Hollywood. In a nutshell, unpopular governments know single men riot first, so a higher level of political discontent can be contained if single men are distracted. If the sex workers suck up public attention and energy through bad behavior, if the behavior of their pimps makes gathering on city streets unsafe, all the better.

Even prior to Maria Theresa, Habsburg policies toward Hungary in particular were designed to facilitate slaving and the sex trade. After the ouster of the Ottomans (themselves notorious sex-traffickers), Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand I (Hapsburg) set up the ‘Military Frontier’ around Hungary, and garrisoned it with troops of non-Hungarian ethnicity, mostly Serbs and Croats. This ‘Military Frontier’ kept expanding via Hapsburg-sponsored resettlement of foreigners there under the umbrella of the military. Author Julius Kemény in his book “Hungara: ungarische mädchen auf dem Markte”(1903) [Hungara: The Market for Hungarian Girls], describes how a mixture of military threat, over-blown pandemic rhetoric, and support of the white slave trade were used to keep Hungarians under Hapsburg control:

The girl-trade was already practiced on a very large scale when the Military Frontier was established. This was supposedly built for the purpose of better protecting Hungary from the plague and cholera. In reality, the military frontier was nothing more than an iron belt consisting of Serbs and Croats, with which the scheming and cunning Viennese politicians had enveloped Hungary, which they had always hated. What golden times those were for the girl-dealers! They only needed to go with their “wares” to the military border that still belonged to the monarchy, for which they did not even need a passport. From there the border guards let the girls destined for Serbia or Turkey be brought across the border for a few guilders even without a passport!

Of course, distraction— whether by pandemics or prostitution— does nothing to address the underlying causes of political discontent. In 1848, after centuries of such Hapsburg policies, Hungary (and other places) erupted in revolution. The Hapsburgs could only put down Hungary’s revolt with the help of the Tsar’s armies. When Hapsburg police came back to Hungary, an unhappy land which knew its foreign rulers were unable on their own to maintain power, the police faced a daunting civic unrest challenge. The police’s response was proportionately vicious; part of that response was a “double-down” on Maria Theresa’s commercial sex policies.

Kemény describes the political events which led up to Budapest’s police force being entirely overtaken by the ‘Galician network’, an international network of pimps and slavers based out of the Austro-Hungarian provience of Galicia, in modern Poland:

The Prottmann police.

The epoque of the struggle for freedom was over. The revolution [1848] was, as they said in Vienna, “forced down". The Austrian 'Soldateska' crushed with an iron fist the country conquered by the Russians. The terrible Haynau, the hyena of Brescia, made his way into Pest-Ofen. He had been appointed regional military and civil commander, and Baron Josef Prottmann von Ostenegg was appointed by him to be police director in the Hungarian capital in order to maintain law and order. Prottmann set up his residence in the building he rented for the police at the corner of Obere Donauzeile and Hochstrasse (today Akademiegasse and Arany Jánosgasse)…

Baron Prottmann's police were almost exclusively a political police force, who regarded the hunt for the escaped rebels as their main task. They cared little for anything else. Prottmann arrived here with a whole staff of Viennese and Prague officials as well as with a myriad of “confidants”, as the detectives were called at the time…

With what anger the patriotic Pest citizenship viewed this k.k. [Hapsburg Imperial] Police is easy to imagine. Everyone withdrew from the police, glanced at them afraid, and one was glad if one had nothing to do with them. Of course, the strange organs of this foreign police, who were not at all familiar with the local circumstances, could never accomplish anything here on their own, so that they were always dependent on the services of local 'snitches', agents or hadats. But who aided Prottmann's administration back then? The scum of the population. Self-serving criminals, ostracized conspirators and other vagabonds reported to the Police Council Krausz, Prottmann's deputy and head of the political police, and offered him their service. These hadachas only got money in the rarest of cases. Baron Prottmann, Polizeirath Krausz and Polizeirath Worafka wanted to enrich themselves, so they didn't give any money. Instead, however, with the greatest generosity they gave the Hadatschen concessions for the operation of public houses, dance halls, night cafes and secret arcades. For example, Hadatsch Berele Preisach, who had betrayed Ladislaus Paloczy's hiding place to the police, received a concession from Prottmann to operate a tolerated house on the corner of Zweimohrengasse and Blauen Hahngasse (today Petofigasse), and Preisach's wife, who went by the nickname "Luft Resi" became famous, opened the still-existing tolerated house in the Stickergasse. A woman who immigrated from Turkey and who later became notorious under the name “die Turkin” received the concession to operate such a house because she had betrayed the whereabouts of Franz Pulszky's wife to the police.

The popular motto of the Prottmann police was: The people should have fun! And Pest swarmed with nightspots dedicated to pleasure, in which all sorts of dissolute, light-shy people romped about. At the “Zrinyi”, the “Pischinger”, the “Turkischer Kaiser”, the “Zwei Pistolen”, as well as in the coffeehouses of the Konigsgasse, hazard games were played all night long, “spinning” (“gedraht”), song and – bought love. In these bars scenes took place which were not only impossible today, but which one cannot believe today. [1903] At that time they were the order of the day. In the dance halls the most obscene orgies were held and in the “tolerated houses” there were indescribable conditions. Anyone who received the concession for a “tolerated house” became the unrestricted owner of the girls who had come into their claws. He bought them, and he then charged them for board, accommodation and toilet in such amounts that the girl, who had either been lured into his house or had voluntarily gone into it, could never “break free” from it. Her debt never diminished, but steadily increased, no matter how much she “earned” every day, and if the girl, tired of this horrible life, wanted to leave the house, she could only do so if she paid every last cent of her “debt”. The police, however, who never bothered about the horrific events in these houses, made sure that no girl went out of their house to the detriment of their "mistress", they even looked with hawk eyes at the girls who had bought themselves out, they watched them under stricter supervision than even the released prison inmates…

"If I amuse people, they'll send politics to the Devil!" That was Prottmann's reasoning, and so he intended one to have fun in Pest. He even gave ample subsidies to the German Theater under a variety of guises, while on the other hand he viewed with suspicion the public who attended the National Theater and had it monitored. That is why the magnates who remained in the country supported the National Theater very generously, even if they had to avoid attending it, since with Haynau and his successor, Archduke Albrecht, everyone was considered a rebel who attended the National Theater.

It was under Prottmann that the international trade in Hungarian women/children became better organized, according to Kemény:

The owners of the 'tolerated houses', who always paid large, secret taxes under the most varied of appellations, had to be careful to always serve their guests with fresh goods. The older girls, who were already well known by the guests of their house, constantly had to be replaced by new girls. This was done quite frankly and freely by way of exchange. The older girls were simply sent to a tolerated house in the provinces, from where the substitutes arrived for them. It was more difficult to get brand new “goods”. This was done by two mediators, a Christian and a Jew. The Christian's name was Christine Hrb, and was popularly known as “the Schneckerl-Madam”. She was a small, hunchbacked, very ugly woman who always wore her hair curled up in old-fashioned "snugs". She knew how to bring the aforementioned pretty, poor working-class girls to houses with brilliant promises.

The Jewish mediator was far more dangerous than the “Schneckerl-Madam”. She lived in Lazarusgasse and was generally known under the name “Chaj Soreh”. Nobody knew her real name, maybe not herself. She was the caretaker in the “Greisbach” house that had been on the corner of Zweimohrengassen and Blauen Hahngasse, in which there was a dance hall. Jewish weddings were held in the “Greisbach-Saale” in the 1850s and 1860s. From there the “Chaj Soreh” knew the poor Jewish girls of Theresienstadt, and among them she recruited the “newcomers” for the “Luft Resi”, “Krebs Emmi” and “Komaromi Rosa”. Later on, “Chaj Soreh” became acquainted with the big exporters, such as Mendel Gross, Leser Schwimmer and Simson Minz, who at that time took over the decommissioned girls from Pest's tolerated houses at ridiculous prices and brought them to Belgrade and Bucharest, where they were sold for serious money. “Chaj Soreh” then began to supply these exporters with the girls “first hand”, and so she became the founder of the Hungarian girls' export trade.

The corruption that Hapsburg policies exacerbated under Prottmann only got worse under his successor Alexis von Thaiss:

Certainly, under the regime of the City Governor Alexius von Thaiss, or rather, under the regime of Mrs. von Thaiss, the situation in the Pest police was downright horrific, because the police were corrupted through and through, lazy and corruptible to their core, but Mrs. von Thaiss did not create these conditions. When Herr von Thaiss became the governor of the city and when he elevated Ms. Anton Linzer, born Fanny Reich, who was of the lowest level of society, and made her his wife, the Pest police force was already in a bad state of affairs, and Ms. von Thaiss can only take credit for making worse these unbelievably bad conditions…

But when she was raised from the yawning depths to a dizzying height, when she had transformed from the daughter of Notl Mattes Thole to Frau von Thaiss, the powerful and influential wife of von Thaiss, she by no means forgot those with whom she suffered hardship, misery, privation and sin. She was in no way ashamed of her past; on the contrary, she was, to a certain extent, proud of it. "Look here - I was like them and have become what I am!" flashed courageously from her eyes. And she did not withdraw from her poor, depraved relatives, from her dubious acquaintances, not shy, fearful nor ashamed, no, she pulled them to her, she called to them: “Come here - I'll help you.”

And they came, they all came. The gang came first. The old father, the worthy Notl Mattes Thole, could no longer enjoy the munificence of his daughter, as he had died far from his beloved Altofen in the deepest seclusion - in Waitzen. Her older sister was married to the burglar Mayer Brick. Mrs. von Thaiss arranged for their divorce, then married her sister to a well-to-do horse-trader, and made her divorced brother-in-law, the burglar Mayer Brick, a well-appointed police superintendent - as the detectives were called at the time. And when the Altofner relatives and the Pest acquaintances - all of whom were of very dubious respectability— heard how lovingly Fanny, that good soul, took care of her relatives and former acquaintances, they all came, and all had some kind of wish in their hearts that dear, good, golden Fanny might fulfill. One wanted a license for a tolerated house (brothel), the second a license for a dance hall, cousin Netti wanted a coffeehouse with hookers, and Aunt Sali wanted a coffeehouse in which the police would never appear when gambling took place. And then a good acquaintance wanted her husband to be employed as a “commissioner”, then her second son employed as a police officer. And the beautiful Frau City Governor granted everything - did everything. But she was just as clever as she was good, and her cleverness told her not to do anything in vain. She did everything that was asked - but everything had fixed prices with her. “Men didn't gift me anything either,” she would often say with a painful smile - and she was right. Anyone who wanted to use her influence - she made them pay properly. A tolerance house cost from 1000 to 3000 florints for her, while a dance hall only cost 1000 florints, a coffee house with female staff (hookers) only cost 500 florints. If someone wanted to become a commissioner, they had to deliver at least 1000 florints -- "but they can earn it back in a couple of months", the wife of the City Governor would console the petitioner, and whoever opted for a civil servant position - it only cost 500 florints! - - And they were happy to pay these prices to dear Frau von Thaiss - because they were served very promptly. "The money - the goods" she said. She did not do credit transactions. Herr von Thaiss loved his wife almost idolatrously to the end of his life, he could not refuse her any wish, and she had SO many wishes. She exercised a downright disastrous influence on the otherwise energetic and capable man. Not what Herr von Thaiss ordered was sent to the police, but what Frau von Thaiss wanted. That means Herr von Thaiss only ever ordered what his wife wanted, he let her guide and direct him like a small child.

Soon the police were teeming with creatures belonging to Frau von Thaiss. These creatures were of the greatest brutality towards everyone, they committed the greatest injustices and swindles, but they were always measured to the tune of Frau von Thaiss, who appointed her most intimate confidante, her ex-brother-in-law, the former burglar Mayer Brick, to be the police commissioner…

Frau von Thaiss was stingy and greedy for money. She wanted to quickly acquire a fortune in order to be independent of everyone. She loved her husband and was secure in his love too. But she did not believe in the stability of it. She didn't trust her own luck. She was always afraid some nasty event would knock her down from the proud height to which she had been raised by a fortunate accident. She wanted to plan for that eventuality by amassing a private fortune, and no means were too bad for her to get it together more quickly. She sold everything - what was available via the police, she took from everyone involved with the police and who was in regular contact with the police. But she particularly cherished prostitution. The matchmakers as well as the prostitutes - each according to their ability. All had to pay tribute: the procuring women, the matchmakers and the brothel owners, even the prostitutes. She imposed a monthly tax on them which her confidante Mayer Brick collected. Whoever paid the tribute punctually had a free hand to everything. But whoever could not or would not pay was persecuted and ruined by the police without mercy. For this purpose, the prostitution department of the police, which was under the direction of the police chief Lestyák, was used with great success. The three commissioners of this department, Doge, Berl and Dietz, were all creatures loyal to Frau von Thaiss. Anyone who did not pay tribute to Mayer Brick on time would be ruined by Doge, Berl and Dietz. The police showed no mercy for such miserable people…

Frau von Thaiss earned a particularly rich source of income from the innumerable White Slavers who at that time came to Pest from all parts of the world. They were shaken-down according to all the rules of the art. If they had paid, they could take as many girls with them as they had paid for in taxes to Mayer Brick. But woe to the White Slaver who felt the severity and brutality of the Pest police. Frau von Thaiss sponsored the girl-trade because it was a rich source of income for her, and Herr von Thaiss's police tolerated it because the rich, golden rain that poured down on the City Governor also fell on them.

Historian of the Galician network Edward Bristow identifies New York City’s branch of the Galician enterprise as Hungarian transplants enriched by the human rights disaster described above.

In light of the Hapsburg policies and their consequences, I’d like to draw attention to the third part of Seagrave’s observations about “bicycling”: “For the most part they [exhibitors] engaged in a different kind of stealing from Hollywood than that performed by the print stealing pirates, although cinema employees were often key access people in those rings.” Bicycling was something that happened alongside film piracy.

In the 1910s and 20s, ‘film pirates’ were people who either stole films from exchanges, or made duplicates of exchange films to sell on to third parties or exhibit themselves. Film piracy was a huge problem for the early industry and movie moguls counted on Will Hays, the same guy they hired to obscure their connection to the commercial sex trade, to take care of the pirates. Hays, as Postmaster General in President Harding’s cabinet, had all the right connections to induce the U.S. State Department to bend over backwards to help him on his mission, Seagrave:

Instructions to make all “proper efforts” to prevent the showing of pirated films were sent out in May 1924 by the U.S. State Department to all its representatives abroad, acting on the request of Will Hays, president of the MPPDA [Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America, Inc]. Hays explained the pirating of movies had become a common practice. Stolen products were smuggled into foreign countries where they were not protected by U.S. Copyright laws and exhibited on a wide scale. State Department agents were also “directed to cooperate” with representatives of the U.S. Film producers abroad who, in turn, had been directed by Hays to prosecute such violations to the full extent of the law prevailing in the nations to which they were assigned.

“Photograph of Will Hays at a Directors Club banquet. Director William Beaudine (right of Hays) and film producer Sam Warner (center background) are among the men pictured.” Hays is dead center front row. 1925.

This image is from the collection of the Indiana State Library Digital Collections, which contains “Photographs from Will H. Hays, which feature subjects such as himself, family members, and people involved in political organizations, clubs, and the movie industry. Hays served as chairman of the Republican National Committee (February 1918-June 1921); manager of Warren G. Harding's presidential campaign (1920); U.S. postmaster general (March 1921-March 1922); and president of the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America (MPPDA) (1922-1945). This folder contains photographs of Hays with his son and nephews in California, Hays with Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks at the Greater Movie parade, and Hays at various banquets and luncheons.

The connection between commercial sex and film piracy is this: to a remarkable extent pirating networks overlapped geographically with Galician pimping networks. Certainly the pimps, as consumers, producers and distributors of pornographic films, also had the means to distribute illicit copies of Hollywood copyrighted films. The global reach of the leading prostitution network, and piggy-backing film piracy networks, was the product of decades of Hapsburg cooperation with the commercial sex trade and slavery. To understand this global network, we need to look back to Austro-Hungary’s “Enlightened Absolutist” trade policies of the 1700s.

Maria Theresa and her father were interested in reaping income from the Mediterranean slave trade which supplied North Africa and the Ottomans with slaves from Europe and Africa. The Mediterranean trade was an ancient one from which the more modern Atlantic trade in slaves (mostly to South America) sprung.

In order to benefit from Mediterranean traffic, Maria Theresa developed the port of Trieste. Trieste was designed to be something of a ‘Wild West’, where the Hapsburgs promised clemency to any criminals wanted elsewhere who would engage in maritime trade out of their port. Maria Theresa adopted this policy from the example set by the Medici family’s slaving port at Leghorn, though unlike Leghorn, Trieste was not meant to have an open slave market, but be a base for ships engaged in the “carrying” of slaves to markets eastward. Naturally, as the decades went by, Trieste became a hub of the White Slave Trade into North Africa and the Ottoman Empire— exactly as Maria Theresa intended.

By the end of the nineteenth century, the principal arms of the the Hapsburg’s Galician prostitution network terminated in the Ottoman Empire (including Palestine, Turkey) and South America (particularly Argentina), with the Austro-Hungarian embarkation points at Trieste (Italy) and Czernowitz in modern Poland. Slave markets in India, South Africa and the Far East were also important, but to a lesser degree. As the 1800s drew to a close, New York became increasingly central to the network, mostly thanks to Budapest’s slavers relocating there. Bearing this ‘map’ of international prostitution in mind, consider the network of film pirates as described by Seagrave:

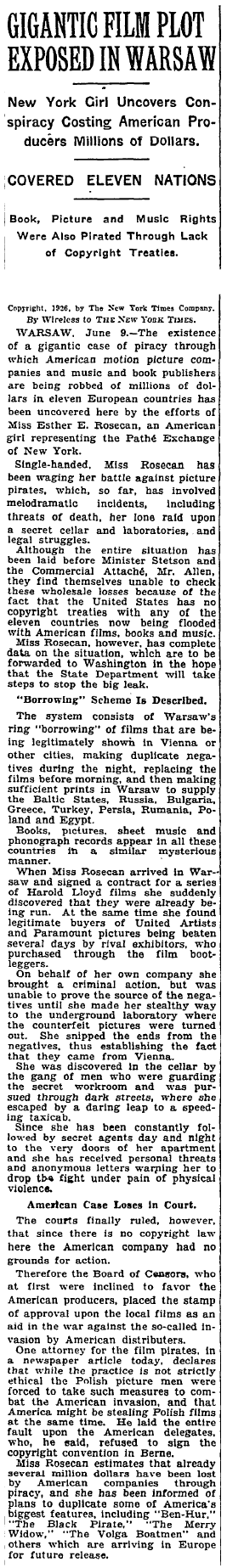

A gigantic case of piracy through which American film companies and music and book publishers were being robbed of millions of dollars in 11 nations was reportedly uncovered in 1926 by the efforts of American Esther E. Rosecan, who was in Warsaw representing the Pathe Exchange of New York.... Centered in Warsaw, the ring “borrowed” movies that were being legitimately shown in Vienna or other cities, made duplicate negatives during the night and replaced the films before morning. Next, they made sufficient prints in Warsaw to supply the Baltic States, Russia, Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, Persia, Romania, Poland and Egypt... One attorney for the pirates declared, in the local papers, that while the practice was “not strictly ethical” the Poles were force to take such measures to combat the American “invasion” and that “America might be stealing Polish films at the same time.”

I’ll point out that such “borrowing” from cities as far away as Vienna would require a speedy mode of transport, unencumbered by the delay of train scheduling, which at this time could only be provided by something like a motorcycle. Seagrave continues:

...The pirating of product in Turkey had been the cause of much concern for several years to the U.S. Industry. Native exhibitor Kemal Bey headed that local organization [of copyright-respecting exhibitors], which was still in its infancy... A court, in a case initiated by Bey, issued an order stopping the screening of the pirate version...

Eighteen months after the above account about Turkey, it was reported that the pirating of films in Turkey had “practically been stopped”... That was due to the native exhibitor organization, which [US commercial attache Julian E.] Gillespie claimed had been formed at his suggestion. Still there was internal squabbling in the group and it was in some danger of an imminent collapse…

Tying the Turkish and Polish situations together was Julian Gillespie, who reported to the Department of Commerce that a Pole representing himself as the agent of a Polish concern had openly sold a pirated copy of Harold Lloyd's “Girl Shy” to a Turkish exhibitor. To make matters worse, that exhibitor was a member of the exhibitor's organization, formed at Gillespie's urging, to eliminate piracy. Loyal members of that association “convinced” the local police chief he should confiscate the pirated film, and he did. That official later returned the movie, however, when the exhibitor “convinced” him his initial seizure was wrong. The Pole in Turkey had further strengthened his position by securing from the Polish Consulate there a letter representing himself to be the agent of a legitimate firm. That letter advised cinema owners that the agent could furnish them with “copies of celebrated films.” …

A lengthy report to the U.S. Commerce Department in 1926 detailed the work of the Polish pirates in Romania. American Consul lat Bucharest, J. Rives Childs, explained the first attempt by the two Poles to dispose of a pirated print was frustrated when film producers inserted a warning in the motion picture trade papers. Persisting, the Poles located an exhibitor who would screen their pirated Charlie Chaplin's Gold Rush (it was re-titled). When the U.S. Consulate sought to stop the screening through the police the film people were met at the police station by the exhibitor, the importer, and a number of lawyers and representatives of the Polish legation. Using Polish diplomatic personnel for assistance was said to be a tactic used regularly by the Polish pirates. Police officials were faced by an apparently bona fide bill of sale on the pirated print while the U.S. Officials were without documentary evidence that the movie was U.S.-owned. As a result, the police did nothing. Finally, the Americans got the necessary documentation and succeeded in securing an order for the film to be seized, after it had screened for three days. A sheriff sent to carry out the seizure order was talked out of doing so by the exhibitor and his lawyer. Another order was secured the following day but the film was gone by then. Later it was learned the movie had been sold to another Romanian exhibitor for $250. After several months-- during which time the film was screened occasionally, and all efforts to stop it blocked-- it was finally seized by Romanian officials with diplomats in Berlin, Paris, Constantinople and Bucharest involved along the way.”

In addition to the countries Seagrave mentions above, the US commerce department was involved in Middle Eastern and South American battles:

According to a report from Richard May, American Trade Commissioner with the Department of Commerce, the pirating of pictures in Palestine had reached the point where the original producers could not dispose of their product to exhibitors. Through the American Consul in Jerusalem, May, acting upon instructions from Washington, had interviewed the Attorney General of Palestine and “It was soon shown that it was necessary to give the film producers protection.” During that interview a representative of an American producer [with Chicago connections] was present with May. While pirates had literally been 'cleaning up”, the question had never before been brought officially to the attention of the Palestinian government for, said May, it was found that motion picture rights could be fully protected there by the fairly recently passed Palestine Copyright Act of 1924...

Producer First National made protests to the State Department in an attempt to protect a Caracas, Venezuela, company that held a three-year distribution contract for its movie The Sea Hawk... [U.S. consul at Caracas Henry W. ] Wolcott also noted that on several previous occasions the consulate had endeavored to use its influence to prevent the exhibition of pirated films, only to be advised by Venezuelan officials that nothing could be done.

While exhibitors got the rap for supplying films to pirates, in some cases the producers themselves were the culprits:

Also, the Film Theft Committee of NAMPI [National Association of the Motion Picture Industry] had agents along the Mexican border. Through the arrest of a Mexican who had several reels in his possession, information was picked up implicating employees in the distribution offices of film producers in New York City.

Contemporary U.S. trade representatives were able to form copyright agreements with all Latin American countries except Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia and Venezuela. Serious piracy problems also existed in Cuba, India, China, Japan, Greece and in some parts of Africa. As stated, the film piracy network bore remarkable similarities to the Hapsburg-sponsored Galician organized crime network… which has unsavory connotations for Rainer Hapsburg.

Child psychologists have written extensively about the “black-sheep” or “ne’re-do-well” phenomenon in dysfunctional families and how often the child labeled as such is not the individual with the most severe psychological troubles. I believe that Rainer Hapsburg was the predictable product of both nature and nurture. Rainer died of blood poisoning at 35 years old, was buried with Emperor Franz Joseph in the Imperial Crypt, and his remaining family were able to attend his funeral in Vienna.

NYT, June 19th, 1926.